It’s been said and often quoted that 10,000 hours of doing anything will make you a master. Never mind the squishy definition of mastery that makes it apocryphal, I believe it.

When the term mastery is used, I figure it’s not that you’ve risen flawlessly to becoming a great chef or engineer, but that you’ve managed to corral dysfunctions enough to let your functional side shine through. This might lead to becoming that great chef or engineer. You’ve mastered crawling out of the trash compactor of life and made something of it. Congratulations.

The theory was first published in a 1993 paper in Psychological Review, “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance,” where 10,000 hours “of deliberate practice extended over more than a decade” is required for mastery. It was later popularized by pop science writer Malcom Gladwell, and the rest is history.

This has been shot down left and right. A Princeton study found that “deliberate practice explained 26% of the variance in performance for games, 21% for music, 18% for sports, 4% for education, and less than 1% for professions.” Gladwell may not be completely accurate, but I’m with him. Putting that much time into anything does something. Please, say it’s true. Each time you fire off a sequence in your head, the brain encases the neural pathway with myelin, a sheath that forms around nerves. Myelin is made up of protein and fatty substances that allow electrical impulses to transmit directly along the nerve cells. A pathway builds. Multiply that by however many hours and you see where we’re going.

I’ve already mastered finding finish lines, my arms outspread as if I’d won. An easy 10,000 hours was spent teaching myself how to hunch over a laptop, how to scribble on paper and walk and hunt for stories. I’ve had 10,000 hours of kids growing up, outmaneuvering me, I’m good at that. Ten-thousand hours of driving, sorry.

Have I mastered writing? I should have by now, tens of tens of thousands of hours, but don’t be silly. Every paragraph is a maze, every narrative thread threatening to whither in my hands. Master of sniffing down dead ends, getting lost, and maybe finding something worth putting on paper. I’ve mastered turning out manic pages that I will later cut, wringing hands over which thread to pick up or put down, the harder nights spent in wide-eyed silence peering at the ceiling, the stars, whatever happens to hang over my head. If this is mastery, I’d pictured something different.

I think of the recently late poet Mary Oliver. She mastered awe, writing, famously, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” Oliver must have spent many 10,000 hours listening to clams, whispering to flowers and trees, and she could say it so damn well. I didn’t know her personally, if she stared at the ceiling all night, but she had awe down pat.

I’ve mastered forgetful proficiency, fool on the hill, getting too little sleep, eating ice cream. I’ve probably mastered ADHD or some other acronym nobody wants. Definitely the keyboard. Most people I can type under the table. For slightly legible handwriting, the pages and backs of envelopes are countless; roses are landing at my feet.

Have I spent 10,000 hours in a bathroom? Please tell me I haven’t.

By the middle of my possibly one century on Earth, I’ve had so much time. Out of the womb for more than 450,000 hours, I could have been an astronaut by now.

There must be a reason it hits about this time in life. How many 10,000 hours are left? What will you do with those precious hours that for the first time you’ve begun counting?

I’ll make lists, check boxes. If I hadn’t mastered procrastination, I’d be amazing.

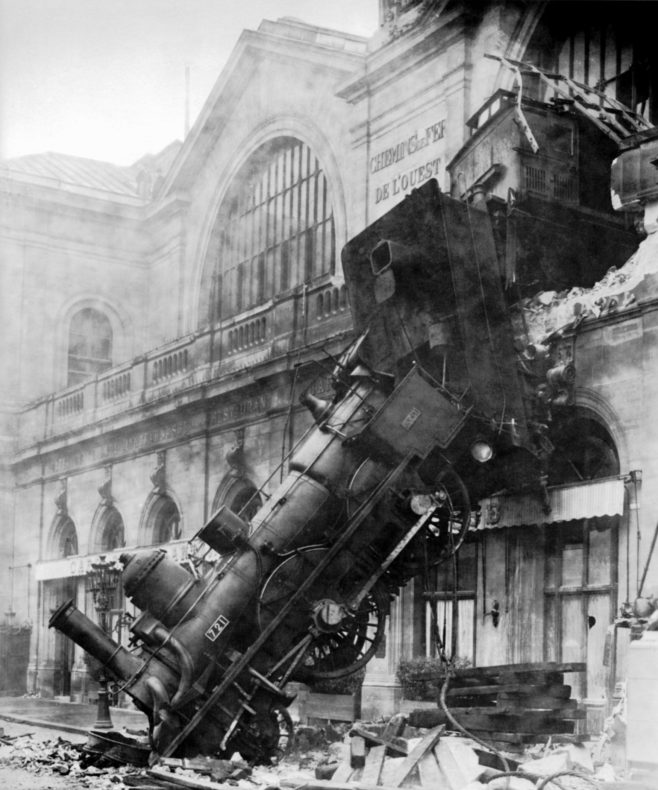

Photo: Train wreck at Montparnasse 1895

Years ago I read a story about a guy in his 20s who had already done many many things. At some point the writer had asked him what drove him forward. That young guy pulled a ratty piece of paper out of his pocket. It was covered in tiny little squares, front and back. He said, ‘This is the average life span. At the end of every week, I fill in a box. This is all I have left. Did that last week matter?”

It’s basically the only thing I remember from the interview. I can’t tell you what that young man did, where he was, or even any bit of his name, just that he knew with certainty that he had just one “wild and precious life” and it drove him on. That affected me.

So I took out a sticky note and made a 9×9 grid on it: 81 squares, approximate lifespan in years. What had I done with mine, so far? Me being me, I colored coded those years. Childhood – 6 yrs. Education – 25 yrs (don’t ask). Work (overlapping with a bunch of those education years) – 30 yrs; many of them either boring drudgery or stress-filled slogs working for little narcissistic dictators in small companies. Are any of those years worth repeating? Raising kids – 20 yrs. Surely the most amazing thing I’ve experienced. But did I spend enough time with them? How many opportunities were lost? I could have taken them out of school more often to go camping; to hell with that fancy babysitting called ‘high school’. Helping my fledglings establish themselves in their own lives – 10 yrs ongoing. When should I help? When should I just listen, hands-off? Was I a good dad? Am I still one? Am I a good friend?

Sigh.

I look at the remaining squares. Maybe a few rows left, now. What will those be? How many will be exciting? How many tragic? How many will I spend as an invalid? Will those squares yield more interesting stories? Will I look back and say, “Hell yes, I carpe’d those diems!”? (Apologies to Latin teachers everywhere. And punctuation people. Sorry. I don’t have many squares left. I’m in a bit of a hurry to live and am letting things fall by the wayside.)

Carpe the hell of those diems Dr D!