This post originally ran January 5, 2016

In the quarter light of a few remaining bulbs in a decommissioned hall of the Smithsonian, Kirk Johnson, the museum director, pushed back drapes of clear plastic. The National Fossil Halls was being undressed for demolition, dioramas and murals half torn down, everything had to go. In his business outfit, a coat and tie and polished shoes, he showed me through shadows of skeletons and cases unbolted from the floor. It was the end of the work day, the knot of his tie loosened.

“Watch the nails,” he said as he stepped across a floor stripped down to concrete and wood. “Some are still showing through.”

The museum outside the hall was closing, guards ushering the last people out of the Smithsonian. It felt as if iron doors had shut around us leaving the space silent but for our footsteps. Passing models of Paleozoic fish being packed into wooden crates, and the skull of a Cretaceous horned dinosaur, Johnson wanted me to see one of the murals before it came down. We’d spent part of the afternoon in the catacombs and cabinets in Smithsonian’s storage, opening drawers on tusks, sloth knuckles as big as softballs and the curved incisors a giant beaver that stood six feet tall.

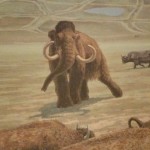

In the hall half torn apart, Johnson was taking me to see a famous late Pleistocene mural before it was rolled up and put in storage. There were actually 4 murals still up, a series of wall to ceiling canvases depicting ancient North America at different, geologically recent time periods. They’d been installed in 1975, painted by Jay Matternes, one of the great museum muralists.

We past his rendering of the Eocene in Wyoming, a warmer, wetter time just this side of the dinosaur extinction about 56 million years ago. Extinct animals were block-headed, tusked and horned with flanged skull was the size of a trash cans. A saber-toothed creodont as small as a house cat was ripping apart a big lizard. Shiny little horses, Orohippus, fled a crocodile and a sort of mountain lion with a pit bull’s face. It looked as if Darwinism were just brainstorming. The first widespread mammals were beginning to feel their legs in the world.

The next mural being unfastened from the wall was of the Miocene, which ended five million years ago, a tropical savanna with muscular long-necked horse-like beasts with claws instead of hoofs. One was fighting off a pair of long-tailed Daphoenodon, the American bear-dog. This was before ice ages. The earth was in its greenhouse phase, still wet and warm but sliding gradually toward a cooling phase. The first snow topped mountains were beginning to hold ice through the summers by the time the Miocene was over.

Next, behind a sheet of plastic, was the early Pleistocene two million years ago when animals started looking familiar. Johnson pulled back the plastic revealing cloud-dotted hills overrun with ungulates, some bearing uncomfortably bizarre horns. Evolution was adjusting to the first extended glacial periods. Ice ages were moving into the picture. We could have been looking at Kansas or Central Texas, far south of the ice caps that came to dominate North America at the time. Tusked proboscideans roamed wooded grasslands along side rhinos, hippos and bears. It was an amalgam of early Africa and America when a northern land bridge occasionally linked one side of the world to the other.

Johnson had said to me, “Time seems like it’s going faster now, you can measure it in minutes and hours. It seems like history is always moving out ahead of us. But now we might be catching up with it.”

I had a certain date I wanted to reach. We had to slow down or we’d skip it. Ladders were propped up to access wires being pulled out of the high black ceiling. A mammoth skeleton had been wheeled next to a case holding the mummified corpse of a steppe bison from Siberia, its withered, bluish body on its knees, forever in supplication, exactly how it died.

Johnson found a power cord and hit the lights. The rest of the hall seemed to go dark as spotlights landed on a mural at the center of the hall. We were looking at central Alaska in the late Pleistocene. One of Matternes’ masterpieces. He’d painted a grassy terrace crowded with megafauna in a broad, treeless river valley. Glaciers in the distance swallowed a mountain range that stretched from one side of the canvas to the other. He’d depicted the infamous wall of ice, the edge of the world.

The concentration of animals Matternes conveyed was impossible, as if we’d arrived at a crowded megafauna convention. Scimitar cats were a jump away from a pride of American lions. A short face bear trotted after a bull elk. A grizzly bear headed the other way across a patch of spring snow, almost sheepishly glancing over its shoulder making sure the larger bear wasn’t taking an interest. A sabercat was posed going after a juvenile mammoth, claws extended but, thanks to the Matternes’ discretion, not yet ripping into the hindquarters of the poor creature.

Matternes could not have resisted putting in our species. It was just the right moment, a verge of history, the most important human moment on the continent. I looked out past a wallflower mastodon hanging at a margin, my eyes tracing in and out of horses and shaggy headed bison with horns spanning ten feet from tip to tip.

“They’re hunting a Jefferson’s ground sloth,” Johnson said.

I looked for the sloth and found five people gathered in a field of short grass steppe. They had encircled this hapless and stolid looking animal, which was reared back on its hind legs. Half a mile away from the rest of the animals, doing their own thing in a far quarter of the painting, the people were dressed in heavy skins and leggings, arms lifted with spears ready to take down their quarry. I’d found the first people.

Images: Craig Childs

A great piece Craig.

Extraordinary writing. To the edge and the Smithsonian. Thank you Craig.

Just a point of clarification — we’re talking about the National Museum of Natural History, right? There are lots of Smithsonian museums, of course.