When I was a teenager, I started writing letters to myself, sealing them, and promising not to open them until a few weeks later. This is how I trained myself not to act on the suicidal thoughts I started having around 11 – the same year I got my period, and around the same age a pediatrician wrote me a prescription for Prozac. If I could wait until it was time to open the letter, something worth waiting for almost always happened.

I’ve always felt embarrassed about those letters, and ashamed of being such an angsty teenager. There were extenuating circumstances –specifically, a non-cancerous brain tumor that messed with my moods and made me lactate (fun!) — but it was nothing worse than what many teens deal with. Why couldn’t I have channeled my emotions into a vigorous sport like soccer (I could barely run the mile) or made friends (too tired and sad) or for God’s sake learned some math?

As I’ve researched a story I’m writing on suicide, however, my feelings toward my younger self have softened. For one thing, it turns out my suicidal thoughts arrived on schedule. In American teenagers, 11 years old — the onset of puberty in many girls these days– is a pretty standard age for suicidal ideation to begin. Researchers estimate that about around 20 percent of teenagers think about suicide, although only a small fraction of teens make an attempt.

Also, it turns out letter writing was a pretty clever trick. Expressing feelings in words engages the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in cognitive reappraisal. Cognitive reappraisal is reinterpreting a negative event in a more positive light. It’s the mental transition from “he dumped me, my life is over,” to “he dumped me, but there’s good reason to believe I will survive.” It’s the difference between “I feel awful – I will feel like this forever” and “I feel awful – let’s get a good night’s sleep and see how tomorrow goes.”

Not coincidentally, reappraisal is one of the main techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. As an adult, I use it to transform thoughts like: “I’m going to file my LWON post late, all will shun me” to “I’m going to file my LWON post late, some people will still probably want to be my friend.”

Scientists don’t know for sure why suicidal thoughts ramp up with puberty. But the researchers I’ve been talking to think it is mainly horrible timing. As teenagers enter the social meatgrinder of junior high and high school, their hormonal responses to stress, and especially social stress, get much more sensitive. Simultaneously, brain areas key to managing stress and making good choices are under construction.

Given all this upheaval, it’s not entirely surprising that some teenagers respond with suicidal thoughts and in rare cases, an attempt, researchers say. Add the adolescent onset of psychiatric disorders like depression — and sexual trauma which increases after puberty and is a major suicide risk factor — and the sharp uptick in suicidal behavior during adolescence is easier to comprehend.

The fact that suicidal ideation is relatively common among teenagers does not make it less serious. It is tempting to think of suicidal ideation as a phase that teens will grow out of, but research suggests this is not the case: people who experience suicidal thoughts as teens are likely to continue to experience them as adults and are at increased risk of death by suicide throughout their lives. Ideation is one of the strongest predictors of a suicide attempt, and although death by suicide is rare among teens, it is increasing, particularly among girls. The problem is global: among all countries that collect mortality data, teen suicide is a leading cause of death.

The researchers I’ve talked to consider this a call to action: even though teenagers often lack the ability to regulate their own emotions, studies suggest that they can learn through CBT and other techniques. The acute vulnerability to social stress in adolescents should also inform how we think about the impact of social media – particularly for girls, who are socialized to invest so much of their self-worth in relationships and physical appearance, scientists say. (We should also make teens safer by dismantling sexism.)

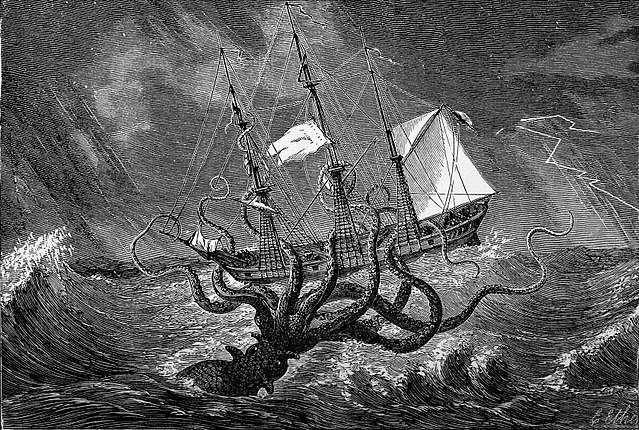

As an adult, I still experience suicidal thoughts from time to time. I’ve always imagined the thoughts as octopus tentacles wrapped around my brain — a dull, squeezing pain, black ink dribbling. Writing letters to myself taught me that the tentacles typically let go within a few hours or days. They are an internal signal that I’m overloaded, that I need go for a hard run (I can run now!), call a friend and get some rest. If those things don’t work, it’s time to seek professional help. Hello, evil octopus, I say when the unwelcome thoughts arise. You and I are not on the same side, but I am cleverer than you, and more patient.

If you think you may hurt yourself:

- Call your mental health specialist.

- Call a suicide hotline number — in the United States, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (800-273-8255) to reach a trained counselor. Use that same number and press 1 to reach the Veterans Crisis Line.

- Call 911 or your local emergency number.

- Seek help from your doctor or other health care provider.

- Reach out to a close friend or loved one.

*This* is one of those things that should be taught in school. If I had known in 7-12 gr how common suicidal thoughts are, I might not have felt so singular in this. If I had known ways to deal with it (e.g. cognitive reappraisal), those years might have been much better than they were. I’ve added this to a growing list of “things I wish I’d learned in high school”.

Thank you for writing this article and revealing a bit of yourself.

It is oddly nice to know we weren’t alone, isn’t it? Thank for reading and sharing your experience, too.

Interesting how we reach out for underwater metaphors, like David Foster Wallace’s great white shark of depression, and its remoras, in “Infinite Jest.” CBT has worked well for people I know. What to do, though, when the impulse is blinding and nonverbal, and so cannot be reasoned out of–as mine were when I was younger?

Emily this is beautiful. Like Dr. D, I also wish I had had this guide when I was a teenager. You always feel so freakish and alone when you’re that horrible, perilous age.

This is a lovely and very appreciated post. Thank you for sharing.