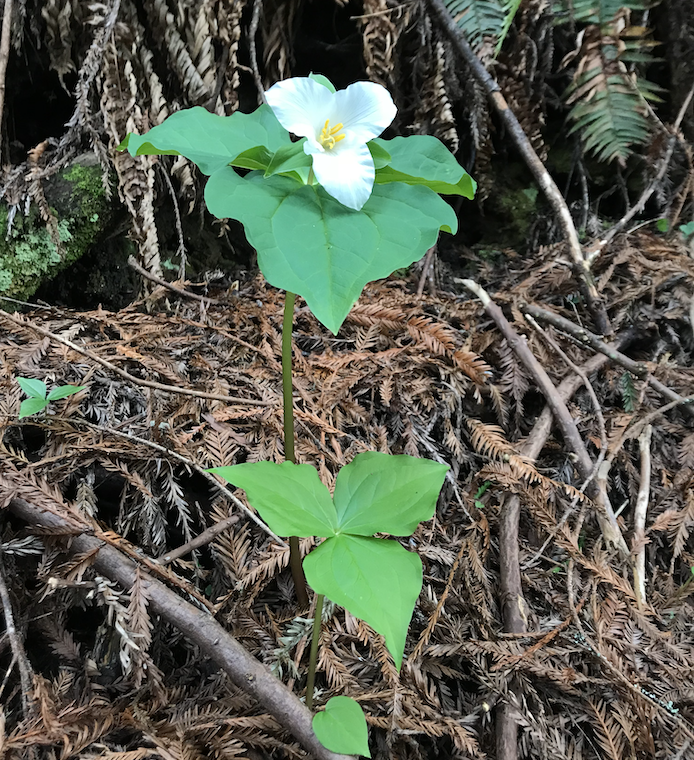

It is spring in the mountains, for I have seen my first trillium.

These extremely elegant woodland flowers are called trilliums because they have just three lovely petals. They are also known as “wake robin” because they traditionally bloom in little patches of sunlight in the forest around the same time the spring robins appear.

My mother taught me never to pick trilliums, because they aren’t annuals; the same plant emerges from an underground rhizome and flowers year after year. They can grow to be over 70 years old.

There are dozens of species, but I am most familiar with Trillium ovatum, whose petals start out a creamy white, then turn to pink or purple as the weeks pass.

Trilium have a deal with ants. The plants produce seeds attached to a tasty morsel called an elaiosome. Ants take the whole package back their nests, eat the fatty, protein-rich elaiosomes, and then throw out the seeds in their trash, where they can germinate in a rich compost of ant-refuse. This mode of dispersing seeds is tidy but doesn’t take the seeds particularly far. One study found 67% of new Trillium plants within one meter of their parent plants.

This slow creep across the forest floor could have made it difficult for trillium to recolonize northern North America after periods in which glaciers covered the land. Luckily for wildflower admirers, there is also a faster route. In yet another entry in the annals of scientists peering into poop to learn the Universe’s secrets, Mark Vellend—now at Université de Sherbrooke in Quebec—and his colleagues found that deer who eat the flowers can poop out viable seed as far as 3.7 kilometers away.

Widespread timber harvest hit trillium hard in the Pacific Northwest. Erik Jules, an ecologist at Humboldt State University in California, spent years studying the reason in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It turns out that mice love the edges of forests and clearcuts. They can eat the seeds of a lot of the sun-loving species there, and the lack of mature forest means there are fewer owls and hawks around to eat them.

Mice like trillium seeds, and unlike ants, they eat the elaiosomes and the seeds. In re-growing clearcuts and nearby forests, there are so many mice that nearly all the trillium seeds are eaten. Sometimes, you can still find trillium flowers in clearcuts. But they are older than the cut, re-blooming and setting seed each year, but without any of their seeds surviving. Jules feared that the enthusiastic harvest of timber in the Northwest would doom trillium in a plague of mice.

But contrary to Jules’ worst fears, logging has dramatically declined in the Pacific Northwest. There are far fewer clearcuts hosting hungry mice populations, and that’s good for the trillium. But the re-growth is not yet ideal for the flower. These plantations, thick with trees all the same age, are extremely dense and dark. There simply aren’t any patches of sunlight in which the trillium can bloom, and the soil isn’t deep and spongy enough yet to make them happy.

On average, Jules says, today’s re-growing plantations are between 30 and 60 years old. “You are looking at it needing to be 90 to 120 years old before it is starting to be good for the trillium,” he says.

In the meantime, populations of the flower in the remaining bits of old forest will probably stay stable, so there will be sources for seeds when the surrounding forest becomes more hospitable to the flower, when some trees start dying, creating gaps in the canopy and building up forest soil.

Jules chose trillium to study because unlike most herbaceous plants, you can estimate the plant’s age by counting leaf scars on its underground rhizome. But he also chose it “because it is beautiful.”

Trillium is really a wildflower for all of us, Jules says. “It is not super rare but it is not a weed. It is a fairly common plant in older forests.” One doesn’t have to be a devoted botanist to find or identify one, nor is it cryptic and tiny. It is easy to spot, showy and bright against the greens and browns of the understory. But it isn’t so common as to be unremarkable. Each trillium is a lovely surprise, a gift all the more wonderful because everyone knows that it is not a treasure to be plucked or taken, but one to be admired, then left to please the next person who passes by.

Just as we share each flower now, so we can share the species with the future by letting today’s plantations mature and open up. It is nice to think that generations that come after us will have more of them that we do, as the ants and deer usher them into forests ripening into a complex, diverse, flower-bedecked early middle age.

Fascinating history. Thank you! Mine are almost open in NE Wisconsin.

We were just out trillium watching today on the Little River Trail just outside Olympic National Park. There were trilliums everywhere, most white, but a few turning pink. We always consider them an important part of spring. We had no idea that they can live for decades, though we suspected. An awful lot of them pop up in the same places year after year, and we’ve been hiking some trails for two decades now.