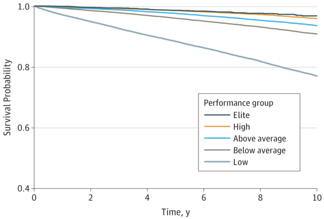

This week, you may have seen the following headline in your feeds: “Not exercising enough is worse for you than smoking and diabetes, study suggests.” For 122,000 patients at the Cleveland Clinic, better fitness—as demonstrated by better performance on a treadmill test–strongly predicted longer lives. Because there have been some questions about possible health risks of extreme exercise, the press release and news coverage focused on the health benefits enjoyed by those with the highest levels of fitness: the elite performers. But the study also reinforces many previous studies that show that a little exercise and a little fitness is better than none at all. On average, the “below average” fitness people outlived the “low” fitness people.

In recent years, study after study have demonstrated that exercise is fantastic for humans. It can help many people fell less depressed and less anxious and can boost everyone’s mood. It can help prevent Alzheimer disease and heart disease. It is so helpful to cancer patients that the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia says it should be prescribed to every single cancer patient. I could go on, but you don’t need convincing. We all know exercise is great for us. The science is overwhelming.

If you are like me, however, you often let exercise get bumped by other things—work, family obligations, endlessly scrolling through Twitter or reading political news, cruising Instant Pot recipes, drinking boxed wine and contemplating society’s inaction on climate change while lying on the floor. You know.

My problem is that I want to exercise right. I want to go all in—to commit to doing yoga three times a week and join a weight lifting class and get back into swimming laps. I want to transform into one of those lean, sculpted exercise people who are forever starting their day with a smoothie and smiling while wearing headbands. And I want to do it all at once. So of course I never do.

This isn’t to say I am a complete slug. I do enjoy a good yoga class when I can make time. I hike with friends and family whenever I can fit it in. But lately, what with the midterms and the colder weather and The Good Place being back on TV…well, you know. Instead I make grandiose mental plans about becoming extremely fit—starting tomorrow.

This is stupid. My visions of perfection are standing in the way of enjoying a more modest amount of exercise. And exercise can be beneficial in surprisingly small doses. My biggest motivation to exercise it to improve my highly volatile and latterly often grim and angry mood. One study from last year suggested that even light-intensity exercise—what one researcher described as “a walk here and there at a comfortable pace”—was enough to provide a mood boost. This year, a review of 23 studies concluded that just ten minutes of exercise a day can make a noticeable difference to one’s simmering rage, despair, and/or feelings of impending doom.

What I need to do—what we need to do—is admit that we are not going to start some super intense training regimen tomorrow. We are not going to be on the cover of Outside or Men’s Health this time next year. But we are going to take a nice brisk walk right now. Maybe just around the block. Maybe more.

Walking is not trendy or glamorous, but it is free and easy for many people. It clears the mind, allows your cramped and overfed eyes to rest on distant and non-digital vistas, and comes with such bonus features as fresh air, spontaneous socialization with neighbors and—at this time of year—leaf crunching. Walking for most of us is a soothing, automatic behavior with extremely deep evolutionary roots. A study from this year shows that the basic neural architecture is some 420 million years old and shared by virtually every land animal–and even some undersea.

And who knows? Maybe we will make it to Extra Hot and Upside Down Yoga tomorrow or pump those bike tires back up and take it to the next level tomorrow. But this is today. And today we will take a walk.

Image: A lady walking along a garden path in profile to right; illustration to ‘The Tragical History of the Children in the Wood’ (York: c.1788-1789); proof. Wood-engraving. Courtesy British Museum.

Some years ago my partner put a sticky note on the fridge that said: “The pursuet of perfection often impedes progress” – including the misspelling which just makes the note perfect.