You know it’s bad when you have to dig a hole and crawl in to survive. That’s what is going on in a creek bed at the bottom of the canyon below where I live. The creek stopped running a little more than a week ago. I walked down the other day and lifted one of the dried stones bumpy with once-living things. A crayfish was underneath, backed as far as it could into a burrow. One small dark club of an eye stared baldly into the sun. The creature hadn’t seen water in several days.

Naturita Creek being dry is something I haven’t seen in the four summers I’ve lived here. Other people who remember at least 30 years say water used to get cut off at a reservoir up top, but mandates for instream flow were established and it has flowed freely ever since. This year, the drought was too much.

At low water, with a running start, you can jump across Naturita Creek. At no water, it’s a chalky bed of stream cobbles.

The crustacean squirmed slightly, pushing itself tighter into its hole. The array of antennae sprouting from its head was neatly folded back into the burrow. I’d been expecting to find a creek bottom strewn with baked, stinking exoskeletons, their claws pointing this way and that. Now I could see these were cunning little buggers. This wasn’t their first rodeo.

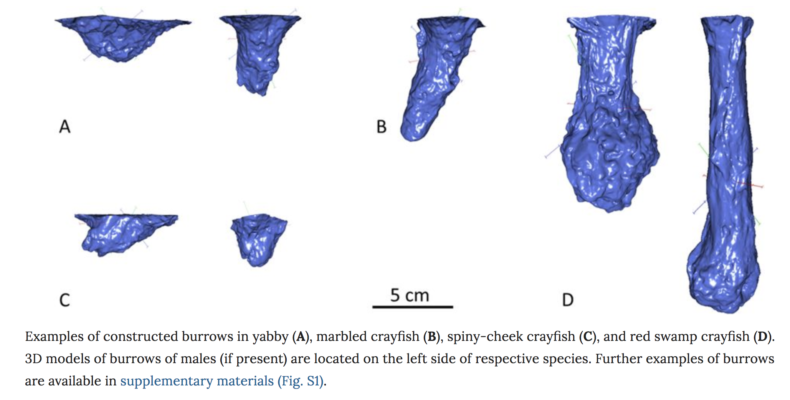

Naturita Creek is well populated with these miniature lobsters, decapods with feathery gills that draw oxygen from water. As long as their gills are moist, they can survive out of water. That’s the limiting factor. A study of several kinds of crayfish showed that some species survived a week of drought, though some were weakened by the experience and died shortly after being placed back in an aquarium. Other species experienced high mortality in their completely desiccated environment, and one lost all its individuals within five days. The species that did best, not one of them dying, was the most proficient burrower, settling underground in a state of torpor, metabolism lowered, gills given a controlled climate by the burrow. This was the red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii, the only species in the experiment that closed off its burrow entrance with a mud plug.

The red swamp crayfish is originally from northern Mexico and Southeast US, and has spread invasively across Europe, Asia, and Africa where populations are still expanding. It prefers warmer waters, able to withstand low levels of dissolved oxygen, reported to survive for months in a drought. It is an ideal crayfish for adapting to drying conditions, which are becoming more common.

What species this was under the rock I didn’t know, nor could I guess how long it might live. Olive green and packed tight, its head was visible, but most was underground.

I once encountered a dried-up creek in the desert of southeast Arizona. It would flow at night, then dry up around sunrise, turning a tunnel of alders and sycamores into a babbling arena, fireflies dancing. By mid-morning, it would be dry again. This happened every day. The culprit was the riparian forest around it. When the sun was up, the trees pumped water to sustain themselves on summer days pushing 115° F. When the sun went down, photosynthesis stopped and the trees rested, letting go of the water table. After sunset, wet patches in sand grew into pools that within an hour began to connect, then flow into each other. Little mud turtles gradually scuttled through pools. Sonoran desert toads screamed at each other. Finger-length fish known as dace darted through fresh currents. In the morning, the trees turned back on, and every living, mobile thing dug its way back into damp sticks and leaves, scratched under rocks, and wriggled into moss cavities. There they sank into torpor as the creek bed roasted in daylight.

My creek was not going to come back tonight. Torpor would have to last a good long while. Rights to this instream flow were established in 1984, while two senior water rights from 1884 and 1885 have been keeping their share, drying up the 1984 creek. It’s a matter of drought and politics, and for the crayfish, biology. Unless rains come hard or we get a good, early snow on the peaks, the creek could remain dry for months.

Every out of focus picture I took of this crayfish under the rock probably stole a day or a week from its life. It’s been a hard summer. Jackrabbits are looking bony and ravens stand around with their beaks open as if gasping in the heat. With wildfires sending up plumes visible out most windows in the house, I’ve been thinking of chipmunks and rabbits baked to death into their burrows, deer bounding with their hides on fire. It’s been hard on everyone, some more than others, but no species escapes. The crayfish shoveled its tail deeper, grinding back and forth, and I lowered to stone into place, sealing the animal, waiting for water.

Photos by me of Naturita Creek, CO; image of crayfish burrow casts from “The significance of droughts for hyporheic dwellers: evidence from freshwater crayfish.”