The Arbor Day Foundation, which I have supported since I became a taxpayer at age 16, has a wonderful program called Tree City USA. To become a Tree City USA, all you have to do is have a tree board, have some kind of community tree ordinance, spend at least $2 per capita on forestry, and celebrate Arbor Day. It’s a good program and an easy one to join, which is why somewhere around 3,400 communities have done so.

But it turns out that being a Tree City USA, or a Tree City Wherever, is also a much more important distinction than you might realize. Urban trees, at least when there are lots of them, can provide as much carbon storage per hectare as a rainforest.

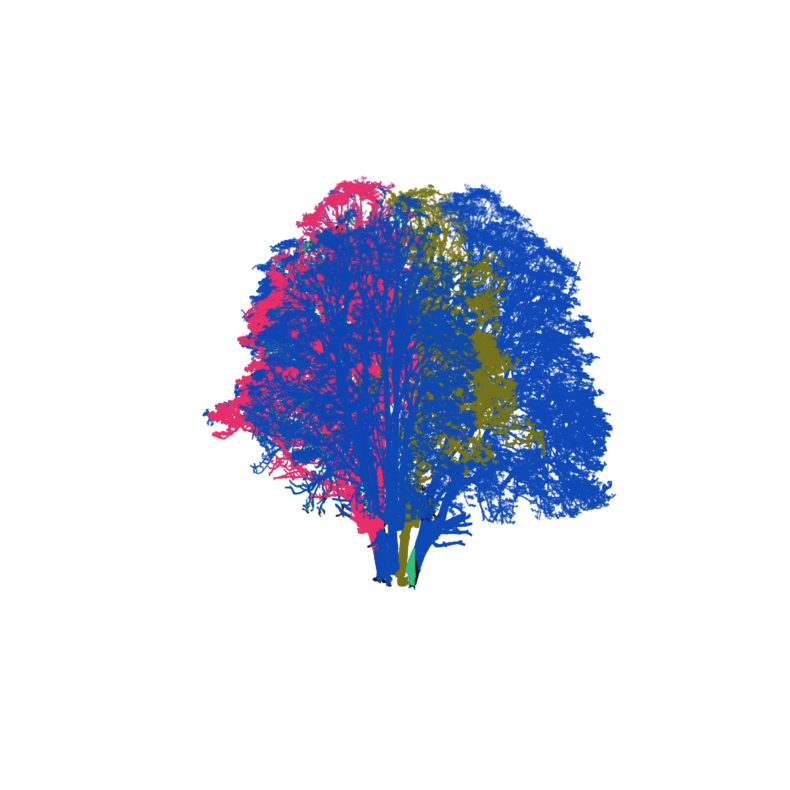

To figure this out, researchers from University College London used LIDAR, which is basically the same as radar but with lasers (and, like radar, will one day be wordified and no longer capitalized). They mapped the size and shape of every tree, all 85,000 of them, in their home borough of Camden (a great name).

The research team from UCL had already done this work in tropical rainforests, where they put together tree density maps to figure out the trees’ structures. It looks really cool — see one here.

By making these ghostly tree renderings, scientists can then figure how much carbon the trees have absorbed throughout their lives. Trees, you’ll recall from the 5th grade, use photosynthesis to make carbon dioxide into oxygen and food. Carbon dioxide can thereby be locked up in a tree’s woody innards for centuries, making trees incredible carbon consumers. Tree-led carbon sequestration is worth $2 billion per year in the US, according to the study.

People have tried to estimate just how much carbon urban trees suck up as a collective, but this is hard to do. City forests are often made up of lots of different species, which are broken up by buildings and roads, making transects and other population-density work more challenging. Also, previous carbon-sink estimates have relied on measurements from trees not in urban areas, which might live different lives than trees accustomed to the vagaries of city life, from bus exhaust to urban heat islands.

To measure Camden’s “above-ground biomass,” geographer Phil Wilkes and colleagues at UCL used LIDAR to detect individual trees. They had previously done this in tropical rainforests, but in their paper, they say this is the first time anyone has used such LIDAR techniques to measure trees in an urban environment.

And what they found was heartening: in some London neighborhoods, urban trees store up to 178 metric tons of carbon per hectare, compared to the average 190 tons per hectare in rainforests. Not bad, city trees!

Unfortunately, this doesn’t mean that we can just carpet our (increasingly more populous) urban areas with more trees to save the world. It won’t be enough. Studies have shown that trees do not gulp down excess carbon and increase their growth sufficiently to mitigate global warming. But I think it’s still nice to know. Those trees on your commute, in your neighborhood, in the park down the street that you wish you wanted to go jogging in — those trees are doing much more than looking nice and giving you some shade. Tree City USA trees are doing their part to fight back against our profligate pollution.

Photo credits:

Top, Flickr user richard777, CC-BY-2.0

Middle: Mat Disney, UCL

One thought on “Save the Main-Street Forest”

Comments are closed.