When Kentwood Wells was 12 years old, he and his parents stumbled across a magic lantern in an antique shop during a Maine vacation. The instrument, an old image projector that used a kerosene lamp for illumination, came with beautiful German glass slides depicting scenes of hunters, soldiers, and children. Wells’ family became fascinated by these historical objects and started collecting them on trips. One of their rituals was to bring a bottle of kerosene and project pictures on the wall of their room. “Luckily, we didn’t burn down any motels,” he says.

Wells grew up, went to college to study biology, and dropped the hobby. He became a herpetologist at the University of Connecticut, investigating questions such as how frogs communicate and care for their young. But after his parents passed away in 2003, leaving him a collection of about 85 magic lanterns and roughly 5,000 slides, he decided to return to the topic. “That was the main motivation—just to do something other than having all this stuff sitting in a cabinet in my house,” he says. Wells began editing The Magic Lantern Gazette, a publication of the Magic Lantern Society of the United States and Canada, and scouring newspaper archives for details about the use of these instruments in 19th- and early 20th-century American society.

The magic lantern, invented in the mid-1600s, preceded the 35mm slide projector and movie projector. Typically made of tin or another metal, it included a compartment for a light source and a concave mirror and lenses to focus the light and project the image. Small magic lanterns were about the size of a toaster, while others could be as big as a mini-fridge. Performers who entertained large audiences often used limelight for illumination, produced by burning hydrogen and oxygen to heat a piece of calcium oxide. Users displayed hand-painted or photographic slides of everything from wildflowers to the Eiffel Tower.

In his newspaper searches, Wells found that these instruments were commonly advertised as toys from the mid-1800s to early 1900s and were available for as little as 25 cents. “Practically every middle-class family in America probably had a magic lantern,” he says. Sellers usually targeted boys; an 1895 ad by the department store Hale Bros. in The San Francisco Call declared, “What better or more instructive present for ‘that boy’ could we suggest? He will stay home nights if he has a good Magic Lantern.” In children’s letters to Santa published in newspapers, girls sometimes tried to get the toys by requesting them for their brothers. One child named Mildred F. Jones in Virginia plaintively wrote, “I want a magic lantern but papa is afraid for me to have one”.

Sunday schools also used the projectors to show Biblical scenes and astronomy illustrations, since the cosmos were thought to reveal God’s creation. The pictures, clergymen hoped, would entice more children to attend. “Ministers throughout the 19th century were constantly complaining that not enough people were going to church,” Wells says. “So these were just mechanisms to get more people in seats.” One enthusiastic reverend wrote to a colleague, “I rejoice to hear of the adoption of any expedient which may increase religious knowledge, or promote the piety of our people… I see no reason to doubt its beneficial effects.”

A couple of years ago, Wells started studying the use of magic lanterns in popular science lectures. Ministers, doctors, and researchers used the instruments to illustrate topics such as protective coloration in insects or Earth’s orbit around the Sun. One amateur lecturer, Charles Came, was a furniture-maker and headstone carver in New York; he gave talks on astronomy and electricity using magic lantern slides accompanied by organ music. Doctors offered sex education lectures, discreetly advertised as “practical human physiology” for gentlemen or ladies only.

One colorful character was Dionysius Lardner, a polymath who started his science lecturing career in England. In 1840, Lardner scandalized British society by eloping with a married woman named Mary Heaviside. According to a historian’s account, the lady’s husband, Captain Heaviside, confronted the couple during their breakfast and beat his rival with a cane; Lardner “saved himself by taking refuge under a piano, while Heaviside seized incriminating papers and threw Lardner’s wig into the fire.” The disgraced couple fled to New York. Lardner then revived his lecturing career in the United States with magic lantern presentations on topics such as comets and the steam engine.

American newspaper commentators voiced their disdain. One wrote, “this Lardner is the same individual who, a year or two since, while in England, destroyed the peace of a happy family… And now the villain, instead of being scoured from all decent society, is invited to deliver a course of lectures in New York!” Prim onlookers were particularly shocked that women attended Lardner’s talks, the implication being that “ladies shouldn’t be giving support to this guy,” Wells says. Still, others praised his shows as “truly enchanting”, “exceedingly attractive”, and drawing “unqualified admiration”.

Alas, Lardner’s success did not last. One night in October 1844, he stored his magic lanterns and slides in a theater in Providence, Rhode Island. A fire burned the building to the ground. After some failed attempts to restart his tour, he returned to Europe with Mary Heaviside, who then divorced her husband and married Lardner.

Magic lanterns have since fallen out of fashion. But enthusiasts can pick them up on eBay or find performers on The Magic Lantern Society’s list of “active lanternists.” The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston is running an exhibition until June 24 about the Phantasmagoria, a spooky 19th-century magic lantern show about demons and spirits.

Wells, now retired, is devoting more of his time to studying magic lanterns. This early technology is not just a predecessor of the cinema but “a visual medium in its own right” that was used for centuries, he says: “Three hundred years of cultural history of something is pretty important, even if most people have forgotten about it.”

___________

Roberta Kwok is a freelance science writer based near Seattle. Her work has appeared in publications such as Nature, NewYorker.com, Audubon, Hakai, and U.S. News & World Report.

*Ed. note: Roberta is not exactly a guest but a respected and admired former Person of LWON who not only is a lovely writer but possesses such technical expertise that she’s called only ROBERTA!

__________

Image credits

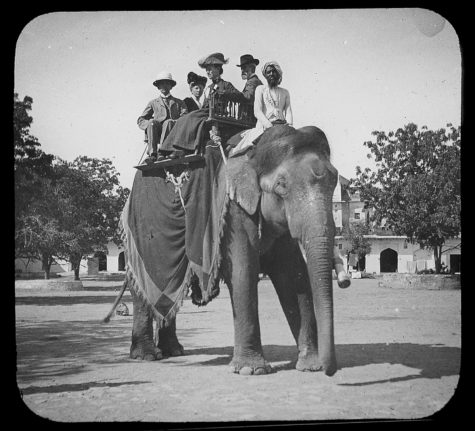

Magic lantern and slide images: Courtesy of Kentwood Wells

Lardner image: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)