Convention centers are funny places. They create insular worlds during any given symposium, but on the margins between those events they hold space for some random intermixing of cosmologies—the kind of interdisciplinary cross-pollination that open-plan architects could only dream of. Such a confluence occurred the weekend before the TED conference in Vancouver this year.

Convention centers are funny places. They create insular worlds during any given symposium, but on the margins between those events they hold space for some random intermixing of cosmologies—the kind of interdisciplinary cross-pollination that open-plan architects could only dream of. Such a confluence occurred the weekend before the TED conference in Vancouver this year.

I arrived early to prepare a workshop and get over whatever slight jetlag exists between North American coasts, but the moment I stepped in the elevator I knew there was more happening here than TED. Four children of different heights stood in boredom with their parents, their hair variously sprayed into a strange high pony tail or woven into a hair piece.

Their eyelashes looked like the rays on a child’s drawing of Mr. Sun. The blood-red lipstick was disturbing, and outlandishly large bows that were not really bows adorned the tops of their heads. These children were cheerleaders, and they were here for the international Sea to Sky Cheerleading Championships.

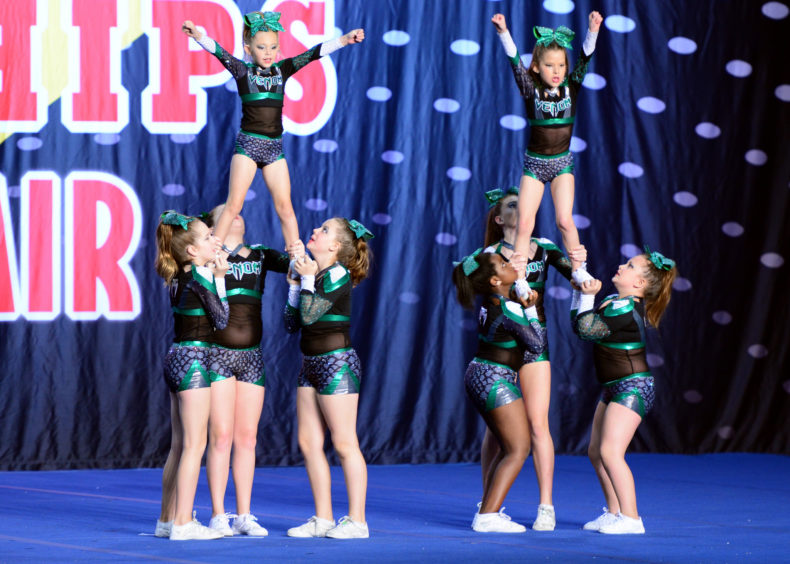

What a hideous distortion of childhood, I thought, as I clutched at the diversion and hurried over to the exhibition hall to pay my $20. Men sported T-shirts that read, “CHEER DAD: The only thing I flip is my wallet,” and other shirts that displayed the Straight Outta Compton logo, only they said, Straight Outta Money. The mothers seemed to fit the stereotype of the stage mother, with way too much invested in their children’s performance. One fierce group out of Seattle, called Natural Venom, bore a striking tonal resemblance to the Borg. Everywhere I saw VENOM ARMY t-shirts on adults and teenagers alike.

I expected some vapid display of vanity, but what I saw on the stage was not girls with the false grins of beauty contestants. Not only were these serious gymnasts, but I saw the girls doing exactly what I had loved to do at their age—memorizing and performing long routines. The bows and the makeup and sexualized outfits were silly, but the activity itself was a true expression of their life stage.

I was never a cheerleader, but I did synchronized swimming, which might as well be cheer in the water. During synchro performances, I spared not one single thought to how we were perceived. I thought only of counting from 1 to 8 and around again to 1. I loved the rote memorization of sequences—together with friends—it fulfilled some cognitive drive that has never been as strong in me before or since. If nobody was teaching them to us, we would make them up ourselves.

This stage of the mind is recognized in the old Latin trivium curriculum, which would peg these girls in the Grammar stage of their education. At this age, in general, kids want to categorize and memorize things. They may enjoy reciting poetry. They might hit their dinosaur phase during this time and learn all of the species names. These days, it would be sorting How To Train Your Dragon characters into types or memorizing crafting recipes in Minecraft. Things adults find boring can be enormously comforting and stimulating to a 9-year-old.

Nowhere was the vacuous cheerleader of pop culture. The same skills these girls developed through cheer would be the bedrock of their later work in building and comparing cognitive models. For all the twisted creatures our modern culture creates, the American cheerleading child did not appear as unhealthy as I had feared. I almost wished I could delay their departures and take a few of them to TED with me.

Image: WalterPro