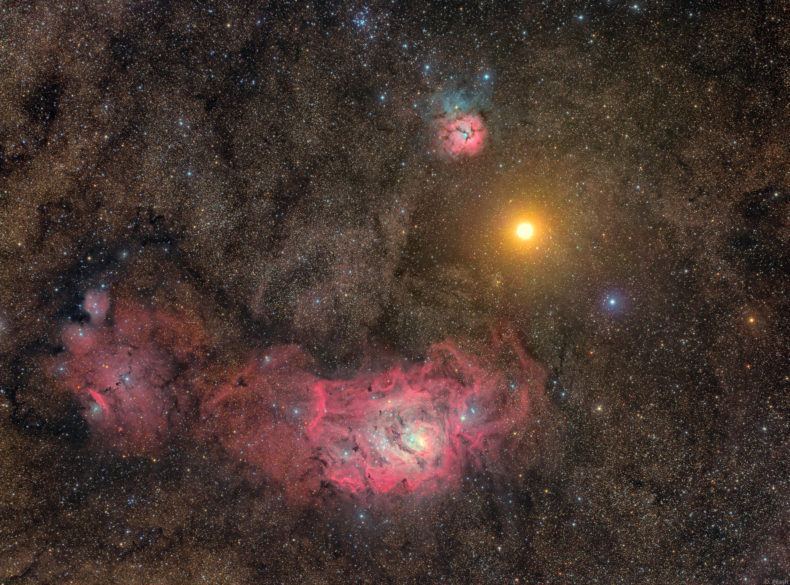

Early on 20th March, professional theoretical cosmologist and amateur astrophotographer Peter Dunsby of the University of Cape Town was imaging a beautiful part of the sky, in the constellation of Sagittarius. When you look at this part of the sky, you’re staring toward the centre of the galaxy, and your view is filled with beautiful nebulae and clusters. Dunsby was using a small telescope, with a lens just a few inches across, yet he saw within it something that shouldn’t be there – a bright, new object, glowing red next to the nebula itself.

Dunsby checked previous images of the same region, both his own, from a few weeks earlier, and from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a survey of the sky carried out a decade ago from an observatory in New Mexico. Neither showed any sign of the object, and so Dunsby took the next, obvious step. Something as brilliant as this object – brighter than all but a handful of stars – would soon be spotted by others; only by announcing quickly what he’d found could Dunsby secure the credit. More importantly, the only plausible explanation for such a bright transient would be a supernova in the Milky Way galaxy, in which case observations while it was still brightening would be essential.

Dunsby turned to the Astronomer’s Telegram, or ATel, service to announce his discoveries. These bulletins, issued to observatories around the world are web based, rather than physical telegrams, but their terse reports still attract the same attention you’d expect if a uniformed courier rapped on the door. Early next morning, astronomers all over the world were reading of what Dunsby had found, and deciding whether to interrupt their observations to follow-up the discovery of the century.

Forty minutes later, a second telegram – number 11449 – was released. It was brief: ‘The object reported in ATel 11448 has been identified as Mars. Our sincere apologies for the earlier report and the inconvenience caused.’

I think it would be wrong to say that the astronomers of the world were annoyed at Dunsby’s brief distraction – little telescope time, if any, was wasted and, as this rediscovery brought cheer to many, not least those who enjoyed cocking a snook at a cosmologist. The ATel twitter feed awarded Dunsby a certificate for his discovery, and even he seems to have enjoyed the mistake, telling Newsweek that ‘The world needs to smile more, so that’s something good that has come out of this episode’.

The episode will be forgotten soon by pretty much everyone. It did highlight, to some surprise, how informal the networks astronomers use are. Astronomers’ Telegrams can be sent by anyone who is a professional astronomer, and yet they have the power to cause people to redirect telescopes costing many millions of dollars. At the largest facilities, such decisions are usually handled via formal requests for what’s usually known as ‘discretionary time’ – a small sliver of the night, held back for use in case of emergency – but in many cases it’s the decision of individual observers. Many of those people will have fought hard for the time they are now asked to give away to follow up on another’s discovery.

My recent experience is that things are getting still less formal. I’m a minor part of the team following up on Boyajian’s Star. Most of the time this object appears to be perfectly normal, but at apparently random intervals it suddenly dims; it has just done so again, suddenly dropping by five percent in brightness in the last few days. This behaviour is so odd that it was proposed that a vast ‘alien megastructure’ in orbit around the star, blocking its light, might be the reason, a hypothesis now ruled out by the discovery that the degree by which the star fades depends on the wavelength of light one observes in. (The idea is that solid objects – megastructures included – block all visible light equally).

Despite the lack of aliens, it remains an object of fascination, but its latest changes are announced laconically, on Tabby Boyajian’s Twitter feed (@tsboyajian). Collaborator Jason Wright (@Astro_Wright) responded to the recent dip: ‘Does anyone happen to have time tonight or very soon on a telescope with an IR camera? Out to 5 microns, preferably’. This, it seems, is how cutting edge science gets done, with a request on Twitter.

Indeed, I strongly suspect that the end of the world might be played out within astronomers’ informal networks. On March 7th, Luke Dones (@lukedones) drew attention to 2018EB, a newly discovered near-Earth asteroid, likely more than 100 meters across. The next day, Tim Lister (@astrosnapper) announced it had been observed again via robotic telescopes in South Africa, and by March 9th that data had shown that the probability of impact was down to 1 in 11 million. A day later, new data had shown that we’re safe from 2018EB for at least the next century. From global threat to yesterday’s news, in a matter of days and all in public.

In a world where science is increasingly done by big teams on large projects, I find it refreshing that astronomical collaboration relies on a bartering network of observers around the globe, all willing to be distracted by someone else’s new discovery. You’re very welcome to follow along too.

————

Chris Lintott is an astrophysicist at Oxford University. He helped found the Zooniverse, the internet’s largest and most redoubtable collection of citizen scientists and science; it’s been responsible for real science; also fun. @chrislintott

Ed. note: as of March 28, “11448 Very bright optical transient near the Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae Peter Dunsby” and “11449 Erratum to ATel #11448” were still the most-viewed Atels.

Photo: Mars near the Trifid nebula, used with the kind permission of Damian Peach