Within the last three years, two of my closer university friends have died. I moved away from Toronto a decade ago, and with those moves I was less frequently in touch with my college friends, but I always assumed we could go on picking up where we left off whenever I was in town. In attending their memorials and hearing more about their lives, I marvel at the changes they made since I lived nearby.

Within the last three years, two of my closer university friends have died. I moved away from Toronto a decade ago, and with those moves I was less frequently in touch with my college friends, but I always assumed we could go on picking up where we left off whenever I was in town. In attending their memorials and hearing more about their lives, I marvel at the changes they made since I lived nearby.

One friend who was unlucky in love all through university met his true match shortly before a rare cancer struck and separated them forever. The friend who died this month once enthused to me that if he put a phone book on his lap, he could eat his Kraft dinner straight out of a hot pot. But in the final years before his fatal drug overdose, he apparently took up cooking as a hobby.

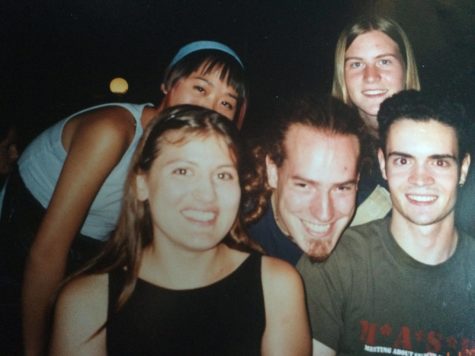

People I haven’t talked to in twenty years are there at the funerals, like some kind of mockery of a class reunion. Twenty years ago, we all lived together in an apartment-style students’ residence, and our friendships were different from any I have now. We had yet to learn the language of emotion that later relationships would teach us, so we couldn’t articulate much of what we felt. In fact, without that intimacy, we didn’t yet know the extent to which others even experienced the world as we did.

We had no use for manners or personal boundaries—everyone else’s dorm room was our own living room. We didn’t yet have real confidence, and so we relied on each other for more elemental things than adult friendships offer. The basic acceptance of my worth was in my friends’ hands, and I’m happy to say they never abused that.

They say that when someone dies, one of the things one mourns is the fact that one fewer person knows the ‘you’ who once existed. Two fewer people now understand who I was when I was 18. I’m not sure I really mourn that part. I don’t miss that me, really. But I’m grateful to those friends for putting up with her, and I would like to honour their memories.

The obituary of the friend who died this month closes with, ‘in lieu of flowers, please do something kind for a friend, as he might have done.’ That’s a suggestion I’m going to take seriously, in the name of friendship.

When we first moved into our neighborhood 25 yo, I would take our toddlers to the play lot around the corner where frequently I would bump into Ruby. She was 94 and spent part of her days walking around the neighborhood chatting with people. She had *fascinating* stories to tell – had lived through both WW, been a nurse in MacArthur’s entourage, watched man land on the moon, seen the entire rise of the technological age. I mentioned that a friend of mine always said he wanted to live to be 100. She said, “Be careful what you wish for.” The most difficult thing, she said, is watching people die. Older distant relatives. A friend or two dies early. Your parents. More friends and classmates. Then … your kids. Maybe a grandkid dies in an accident. “Soon,” she said, “if you’re not careful, no one knows who you are and all the people you share in-jokes and heartfelt experiences with are gone. It’s the worst kind of alone.” So she spent her days getting out and making new friends. Having new experiences. Passing on the stories of her friends and family now gone as if to share time with them for just a little longer and with new people.

Re Ruby: Yes.

I am learning the truth Ruby spoke.

Me too, Ms. Mary.

Thank you for those thought provoking words, and for the feelings they stirred as I read them…