I’ve got a confession to make. Despite living in the age of the BuzzFeed quiz, I’m not one for personality tests. I don’t know what Harry Potter house I would be in, what Myers-Briggs type I am, what “Big 5” personality type I have, or what Disney Princess I would be.

But recently I have been thinking about my personality, my shortcomings, and how I might try to think about changing things about myself that I don’t like. I don’t mean things like “remember to take off your makeup even if you’re really tired you garbage monster.” I’m talking about bigger things like “be less quick to dismiss things out of hand.”

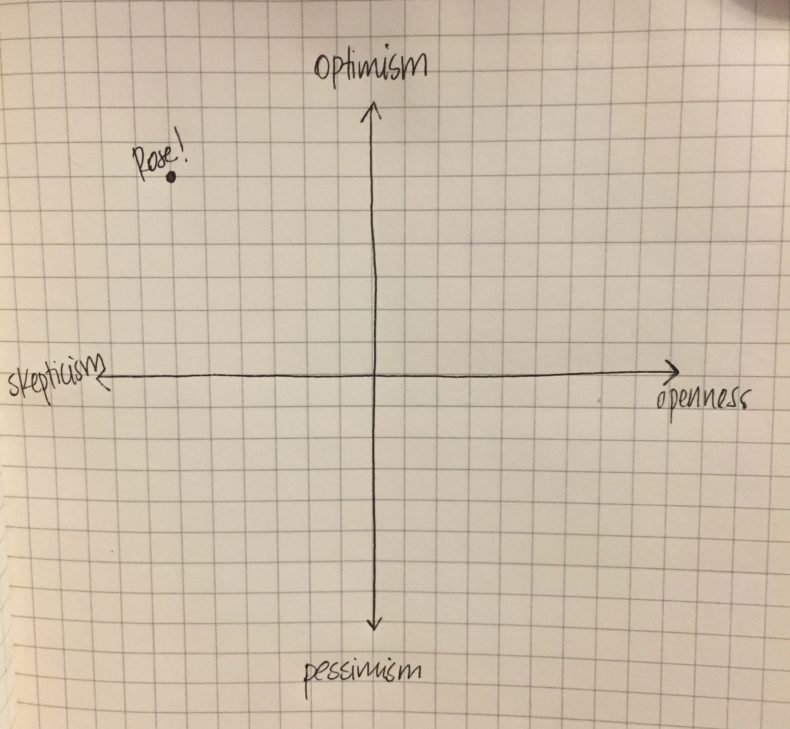

In order to really change something like that, I need to understand my baseline personality, and figure out where that quick judgement comes from. So I’ve developed my own little personality matrix, which I am very maturely calling POOS. As in, many poops.

The POOS matrix has two axes: optimism/pessimism and skepticism/openness.

So in my matrix you can fall into four main boxes:

The Open Optimist: This person is very nice and lovely and perhaps a bit gullible and easily confused by the world. But so nice! The nicest.

The Open Pessimist: I’m guessing this is the rarest of the types here. This is someone who is open to the world, and ready to believe all sorts of things, but also thinks that everything will end badly. Someone who is so convinced that everything is going to go to shit, that they’re just willing to sit back and let whatever happens happen.

The Skeptical Pessimist: This person is not very fun at parties or on the internet. Hobbies include: yelling at people about religion, ruining magic tricks and choosing very sensible footwear.

The Skeptical Optimist: That’s me! I’m skeptical of all things, but also generally positive about the world and how things are going to turn out.

Now, you might think that skepticism and pessimism are the same thing. I argue that they are not! I can be skeptical that dinner will turn out well, but optimistic that perhaps this time I will not completely screw it up.

I may be biased, but I think skeptical optimism is a good place to be. And I think it’s inherent in the work of journalism. As journalists, we’re skeptical by nature. We ask questions and want to know how you know that and why that’s true and are you really truly sure? But we’re also, generally, optimists. We believe that our work can and will make the world better. We take jobs at websites that will almost certainly fail, and scrape a living together without health insurance because we believe that this is an important thing to be doing. Journalists risk their lives because they think that if people could just see what was really going on, they’d make a change, they’d do something about it. Our whole field is built on skeptical optimism.

Personally, going back to my quest to be less judgemental, it means moving my little dot a little more to the right on the openness scale. Maybe just a couple of millimeters at a time. But now that I have this chart I can check in with myself, and plot my progress. It might not be science, but it will definitely make me feel like I’m doing something.

So where are you on this scale? And where do all the Disney villains fall? I must know.

I’m in the same quadrant as you, Rose, but a square or so west and several squares, too many squares, south. That’s not always a comfortable place to be and I tell myself to work on having faith.

I have been dragged through personality tests in the past to no good effect, so immediately (the skeptic side winning for the moment) find a reason to argue with yours. But I argued about Meyer-Briggs, too, so it’s not a personal attack. The only innate personality traits identified in (and it’s hard to know how “innate” and “basic” they are, since even young infants used in the research have had constant contact with humans. Some approach “novelty” at once, some are “slow to warm” and some avoid novelty all the way until it isn’t. Impossible to know how much of that is developed from experience (and a day’s experience to a two-month-old is a much higher % of their total experience than with a 4 year old–or an adult.)

As an older adult, with a lifetime of watching people and experiencing people (including myself) I’m aware of how the traits often listed in personality surveys depend on context: individuals may be eager to engage in novelty in one context, and novelty-averse in another; the strength of any “trait” goes up and down. Adverse events (being sick, very tired, hungry, in pain, having just been scolded, having flunked a test or been fired from a job, having quarreled with a friend, having been put down) change the vector of “openness” in most people to varying degrees. So do positive events, mostly (but not exclusively) in the opposite direction: when things are going well for them, most people become more open to [some] novelty, but will easily shy from novelty they believe might threaten their current safe/happy state. It’s not as simple as ‘optimism/pessimism’. And the oversimplification in one supposed axis multiplies when categorizing a personality on the basis of combination of linear axes. Your system has four possibilities–Meyers-Briggs has sixteen–and still isn’t enough, not only in “not enough axes” but in “not enough consideration of the experiential dimensions (and there’s more than one of those: the obvious are “individual” and “structural” adverse bias in that experience. A child who faces an adverse response from one or a few people who don’t like her for personal reasons–something that she can get away from by avoiding them, or (if they don’t like her because she’s rude and mean) by changing her behavior, versus a child who faces widespread social disapproval because of her race–something she cannot escape by moving, changing her behavior, anything. )

So while I find personality types useful in creating (secondary and tertiary) characters in fiction, I don’t find them useful in real life, dealing with real people, or in self-examination.

You would be Moulin, Rose. She counts as a Disney princess, right?