In this month’s issue of National Geographic, I tell a story of an ancient dynasty of Maya kings who made perhaps the region’s best attempt at creating what we might call an empire. It’s a twisting tale of political maneuvering and ambition unlike any other in the Pre-Columbian world.

In this month’s issue of National Geographic, I tell a story of an ancient dynasty of Maya kings who made perhaps the region’s best attempt at creating what we might call an empire. It’s a twisting tale of political maneuvering and ambition unlike any other in the Pre-Columbian world.

It’s actually kind of incredible that we have the story at all. The reason we do is because the Maya were the only culture in the Americas to devise a complex form of writing. Originally, archeologists thought the bizarre scribbles on the sides of pots or walls was either pictograms – more of a stick figure cartoon – like the Mexica (Aztecs) used or else maybe a series of spiritual astronomical images – more of a drug-addled vision quest. But it wasn’t until the 1970s and 80s that experts realized that these bizarre pictures were neither, rather they were a complex form of writing that I could theoretically use to write this post.

So what is this form of writing? Isn’t it just a bunch of squiggly lines and wacky pictures? Well yes. And no. As I have written before on this blog, our own form of writing began in a similar way – a series of pictures of swords and oxen and other images. And just like the Maya, ancient peoples in the fertile crescent started adding rules and sounds to their collection until we ended up with the modern alphabet you are reading now.

In the story, I profile many incredible characters – both historical figures and the scientists who study them. But the real central character isn’t a person at all but an emblem glyph for the Snake kings.

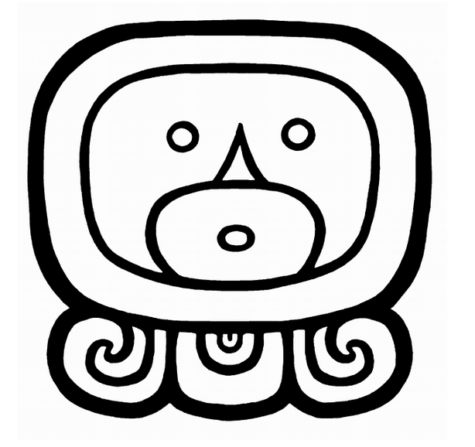

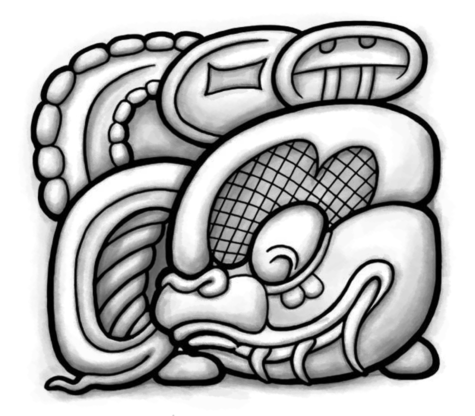

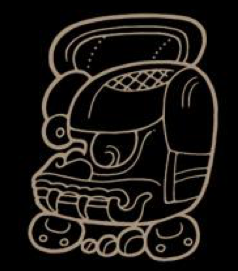

Or maybe I should say glyphs, because every writer among the ancient Maya often had their own style. All of these say the same thing as the glyph above.

Emblem glyphs were a sort of coat of arms or a flag that identified where your allegiances lay. But they were also phrases. For instance, the Snake emblem glyph above reads “ajaw k’uh kaanul” or “the holy lords of the snake.” Ish.

Let me break that down. Start with the word ajaw or “lords,” which looks like this: ![]() Unless it looks like this:

Unless it looks like this:

The confusion comes in because almost any glyph can be written by itself (the latter one) or smushed in with several others. Think of it like a Maya contraction, I suppose. Thus a single square on a Maya tablet can be either a word, a phrase or a whole sentence. If you want to be fancy, cram a bunch of words into one glyph. If you don’t have room, as with this spine used for – there’s no nice way to say this – penis blood sacrifices, then write each word out.

![]() The next part of our phrase is k’uh, which means “holy” in this case. But it also references a bloodline, which may explain why it looks a little like drops of blood but not why those drops seem to be falling onto a shell. Nevertheless, every great city used the same phrase and the same words to designate a great dynasty. And if you get use to seeing them, you can start to spot them all over the place.

The next part of our phrase is k’uh, which means “holy” in this case. But it also references a bloodline, which may explain why it looks a little like drops of blood but not why those drops seem to be falling onto a shell. Nevertheless, every great city used the same phrase and the same words to designate a great dynasty. And if you get use to seeing them, you can start to spot them all over the place.

Lastly we have the city name, in my case Kaan, Kaanal or Kaanul, depending on how you want to read it. That’s the crazy-looking snake, though as you can see above, any image can work to represent your city. Just what that snake means isn’t clear and this is where glyph-reading gets tricky. You see, the Maya also had a sort of punctuation. If you look at the various snake heads above, you’ll see that some of them put dots below the snake while others don’t. These aren’t words as much as a sort of suffix. Erik Valazquez, a brilliant epigrapher at the Autonomous National University of Mexico, says you can think of them as meaning “ish.” The snake-ish people. Or maybe “ville.” The people of Snakeville, where there are lots of snakes.

Or maybe just skip it, as many of the ancient writers seemed to do. But between the different styles, punctuation and contraction choices the scribes made, it extremely hard to figure out what’s what. Take one of the earliest Snake kings I describe in the story: K’altuun Hix, or Bound-Stone Jaguar.Except a few years ago experts realized they had read his name wrong and it was actually more like Tuun K’ab Hix, or Stone Hand Jaguar.

Or maybe just skip it, as many of the ancient writers seemed to do. But between the different styles, punctuation and contraction choices the scribes made, it extremely hard to figure out what’s what. Take one of the earliest Snake kings I describe in the story: K’altuun Hix, or Bound-Stone Jaguar.Except a few years ago experts realized they had read his name wrong and it was actually more like Tuun K’ab Hix, or Stone Hand Jaguar.

Either way, the writers seemed to be describing something that’s hard to wrap our minds around. Similarly, Jaguar Paw Smoke gets reinterpreted as Jaguar Claw and then Fiery Claw. One expert told me that the problem there seems to be that “claw” was meant as a verb and not a noun.

And to add even more complexity, the ancient Maya scribes had a choice to either spell something out (like P-r-i-n-c-e) or else use a proper noun sort of shortcut (as in, whatever that love symbol was that The Artist used in the 90s). And without a lot to go on, it can be tough to figure out what you are looking at. Suddenly it becomes clear why the translation of ancient texts is anything but.

However, what is amazing is that there were rules and from one city to the next, people used roughly the same complex written language. And so can we. Though admittedly it would be infinitely easier had the Spanish missionaries not decided that Maya writing was Satanic and burned the thousands of Maya books including, I assume, one about grammar. But it does make being an archeologist that much more interesting. For example, when I was on assignment, researchers found a fragment of bone with writing on it inside a burial in Sak Nikte’ – formerly called La Corona and even more formerly called  . It looked like this:

. It looked like this:

Can you see the cartoon head at the top? For a brief moment everyone was excited. Was it a snake? Could this be a Snake queen of some kind? The significance could be huge. They waited with baited breath as an epigrapher thousands of miles away looked at photos of the piece. Finally, he said no. It’s not a snake, it’s a shark. And the scientists went back to work. I guess it all just depends how you read it.

Photo Credits: Simon Martin, Erik Vance, Prudence Rice

Erik, According to Zach Zorich’s Archaeology article of 12/13/12, the movement of the planet Venus held a special meaning for the Maya. “Tables that mark Venus’ position throughout the year are recorded in ancient Maya books called codices and on monuments throughout the Maya kingdoms.” Erik, I’m an amateur astronomer who observed Venus transiting (crossing in front of) the Sun in 2004 and 2012.

Knowing of the Maya interest in Venus, I’m wondering if they ever recorded a transit of Venus across the Sun. Even if they didn’t have telescopes with dark filters, they could have eyeballed Venus on the Sun in

puddles or through clouds, or even naked eye on a rising or setting Sun. Since they kept track of Venus’ movements, they should have known when it was heading for a rendezvous with the Sun.

Sincerely, Herman M. Heyn

Web: hermanheyn.com