This is the third and final post in a series about learning a foreign language long past the age when it comes naturally (if you missed the earlier posts, you can find them here: part 1, part 2) . Guest Veronique Greenwood begins at the pro level, with Chinese.

On Monday evenings, I ride my bike into the leafy faculty quarter of the university and teach four ten-year-olds in English. Very suddenly one night, around 6 pm, I started to hear the particles in their speech. They holler and chatter at each other in Mandarin until I shush them and make them speak English, and now my own knowledge of their language is such that these specific parts of speech jump out at me. Even when I don’t understand the rest of the sentence, they tell me something about what the kids mean.

Particles contain information about the speaker’s desires and expectations—even the tense. They can transform the meaning of a sentence, but they’re simple, single syllables—ne, ba, le, la, among others—and so you can start to pick them out, the same way someone learning English might hear “the,” “a,” and “and” in my words. A “ba” often means that someone is asking for confirmation. A “le” often means they are speaking about something that’s past. A “ne” asks a question about something that’s already been mentioned. A “la” makes an order sound more like a request.

These exist in part because Mandarin uses tones to convey meaning and thus cannot use them to convey emotion or expression quite as easily as English. Instead, a particle climbs on to the end of a statement and gives it the specificity that we would give it with the rising and falling of our voices.

–

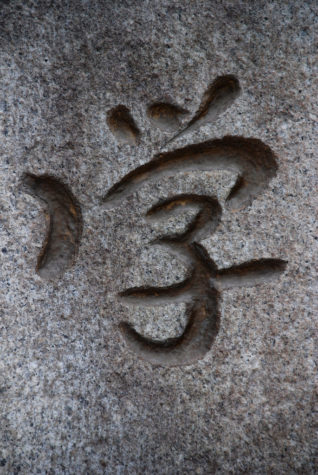

There are other little clues, too, that start to leap out at you. In the classroom, my teacher writes several characters on the board, looks over her shoulder at us, then draws each of their little pieces separately. “Person,” she says. “Water.”

Radicals are fragments that crop up again and again in characters. It helps to think of them as little drawings—the water radical looks like three drops of water. The person radical looks to me like a little man wearing a hat. They sometimes give hints as to what the characters mean: The water radical shows up in words that involve washing or swimming. The person radical appears in words about people, like pronouns. If you recognize the radical, you can guess the meaning of the word. And you can remember it better, because it takes a random assortment of lines and creates meaning from them.

Currently, however, my primary use for radicals is telling the shampoo bottle from the conditioner.

Exhibit A: The conditioner and shampoo bottles as they used to be:

Conditioner is yellow and shampoo is blue. Easy, right?

Exhibit B: Conditioner and shampoo bottles now:

My first thought was, is this post-redesign, or manufacturing error? Did they run out of yellow tops and just had a few tons of blue ones lying around, and spared nary a thought for we illiterates? But actually it looks like I was just unlucky enough to pick up shampoo and conditioner of the same type the second time around. The old conditioner is scented with “the tuber of multiflower knotweed.” The new one and the shampoo just say “deep moisture.”

At any rate, now almost the only way I can tell which is which in the shower is picking up the bottle and squinting at it. The word for shampoo has a water radical in it, indicating its role as a washing tool. The word for conditioner has a hand radical in it, indicating its role as a protector, or coverer, of your hair. I have yet to devote many hours to radical study, but these are two I’m never going to forget.

–

The days grow hotter. Months are passing. Every week, I file into the classroom with the Congolese girl and the Egyptian tour guide and all the others. And now, something deep in my brain has clicked, and one night I am washing dishes and I hear in my head:

“Kan dian ying.”

“Mai dongxi.”

After a few seconds I process them as “watch a movie” and “buy things.” Thank you, brain, I think. That probably means that they’ll be stashed somewhere in that rat’s nest you call recall when I need them.

Not too long afterward, I do need my words. I’m in a not-great part of town, and I’m trying to catch a cab home. I slip through a gap in a fence along the sidewalk to reach the road and walk up to an idling car. I say, “The south gate of the university, can you go?”

The cabbie looks at me and says, “South gate of the university, 60 bucks.”

“No,” I say. “Run the meter.”

“No meter,” he says slyly.

“I won’t,” I say. “I won’t,” and I walk back towards the gap to get back on the sidewalk. But it’s been closed by a bike lock. On the other side, a pair of policemen with the key are lounging in folding chairs. I ask them to open it. They look at me, but say nothing.

All this time I’ve been focusing on learning language. But sometimes language is superfluous. It’s very clear what the policemen are feeling. They’re enjoying this.

So I walk out into the traffic, far, far out. I flag two more cabs and fight with them. I can hear the policemen calling now, and I can understand them—they want me to come back. I don’t turn around, and the next cabbie I hail doesn’t try to give me any kind of a deal. I climb into the back.

I’m pleased to find that even when I’m furious, I can talk. Just a little, but it’s enough. I am beautifully polite to the cabdriver. I remember the right forms of address. I tell him where to pull over. I pay him in precisely the right change. And then I walk in through the south gate of the university, back to the classroom.

______

That’s all, folks! The rest of the series can be found here:

Learning to Talk All Over Again

Shop Owner! Bring Me a Sheet of Table!

Veronique Greenwood is a science writer and essayist whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Aeon, Discover, Popular Science, and many others. You can follow her on Twitter at @vero_greenwood.

_______

Meanwhile, the People of LWON got so excited about Veronique’s posts they decided to write their own, probably about the co-variance of language abilities, reading speed, and accents — or maybe not. Anyway, today’s post is the end of one series and tomorrow is the beginning of the next.

4 thoughts on “All the Chinese You Need to Take a Shower”

Comments are closed.