This is the second in a series of posts about learning a foreign language long past the age when it comes naturally (if you missed it, here is part 1 ). Guest Veronique Greenwood begins at the pro level, with Chinese.

A month into learning Mandarin, I notice that something has changed. When I am out riding my bike now, the sea of sound that surrounds me at all times sometimes parts, and words leap out. On my way to teach English to some kids the other day, I heard the word “now” three times. It’s staggering the clarity with which I hear things I would not have noticed a few weeks ago.

On the university campus, the azaleas and camellias are blooming. The place is full of birds whose songs I hear but whom I can never see in the thick foliage. And today it rained like there was no tomorrow, starting with a hiss and rising to a roar as it pounded against the courtyard tiles. I picked my way through leaf litter and bent ferns to reach the teaching building. In the lobby, I encountered an army of umbrellas, like the tents of a very damp invasion force. Spring is definitely here. Up in the classroom, the windows were open, and the calls of the birds distracted me while I was trying to understand a new measure word.

What I’m realizing now, having never thought about it before, is that nouns in English fall into two categories. There are things like “a sock” or “a table,” and there are things that you preface with a unit, like “a cup of water” or “a pound of flour.” You wouldn’t usually say “a flour” or “a water” (unless you were really saying “a [bottle of] water”). If you think about it, you’ll see that English nouns fall mostly into the first category.

But in Mandarin, a huge proportion of the objects in the world, from paper clips to computers, falls into the second. Each is spoken of as if it were part of a greater whole—a drop from the great well of sock or table. To say “a sock,” you must say “one unit of sock.”

And it has to be the right unit, or measure word. A sheet of table, a handle of umbrella, a stick of pencil. The measure words sometimes make a kind of spatial sense. You have strings of cooked noodles and rivers—but you also have a string of headline, a string of rule, a string of toilet paper rolls, a string of dog. Cigarettes share a measure word with guitar strings and matches.

Who decided this? Who looked at their dog and thought, “Definitely a string.” Who decided that guitar strings and cigarettes were related?

But the measure words are not negotiable. Creativity is not allowed. If you hazard a guess (shouldn’t pizza come in the same units as tables? They’re both flat), it produces the strangest kind of cognitive dissonance for a Chinese listener. When I called a chocolate bar a loaf, the teacher looked at me like I had lost my mind. “Chocolate does not come in loaves. It comes,” she said, as if talking to someone not very smart, “in sticks.”

—

You just have to learn measure words, the way other people have to learn every strange quirk of English. And of course, when it comes to learning arbitrary information: Flashcards are the way and the light, y’all.

I’m not saying anything that’s never been said before, but when I found out with less than 24 hours’ notice that we’d be having a test, I was not sure how much I’d actually be able to cement in my mind beforehand. I spent all morning making flashcards—at least a couple hundred—and sure enough, when I looked down at the test sheet, I knew what was going on. Amazing to me that I can know these things. I, busy knowing so many other things, also know some of these.

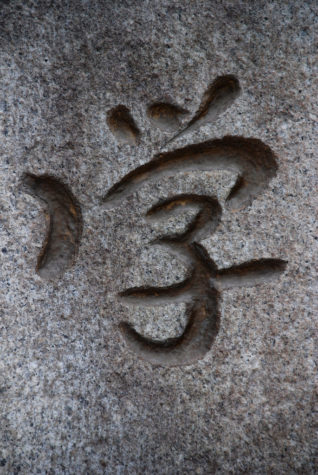

My handwriting still has a long way to go. One night, proud of my sentence-making skills, I wrote on a piece of paper, “Shop owner, I will buy a beer.” When I showed it to my husband, he laughed. Was there something wrong with it? I asked. Did I get something wrong? No, he said. It just looked like something a six-year-old might write on a Mother’s Day card.

—

But despite my best efforts, a tidal wave of information is engulfing me. When I got to class the other day, Maged the Egyptian tour guide, usually the most talkative and hardworking student, had a glazed-over look. “So many characters,” he murmured. “I don’t remember even what we learned two weeks ago.” And in the middle of learning the names of colors that lesson, I felt the class recede away from me and I thought, “I will never go back and learn if a chair is really a sheet or a handle. There’s too much.” I felt a great fatigue at the enormity of the task of learning a language.

The street market near my house gives me hope. If I’m honest, it’s what I first thought of learning Chinese for—so many things to buy, no way to buy them, so many interesting people, no way to talk to them—and when I go back there I can see all the possibilities opening up again. The mushroom sellers have an easy physical affection for each other. They’re a young couple, and the wife leaned over the husband’s back to give me a basket to sort my oyster mushrooms the other day. Since it’s spring, the market is full of odd things people have dug up and put up for sale—bamboo still covered in red clay, unfamiliar roots, edible branches, thick-stemmed wild mushrooms. At one stall, next to a basket of long-necked turtles, I saw a bowl of live scorpions.

“Tasty?” I asked the woman selling them. I could believe anything. “Not for eating,” she said, and after that I lost it, but even to know that—were they for feeding the turtles?—was something.

______

Next up next Monday: All the Chinese You Need to Take a Shower

Last Monday: Learning to Talk All Over Again

Veronique Greenwood is a science writer and essayist whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Aeon, Discover, Popular Science, and many others. You can follow her on Twitter at @vero_greenwood.

Japanese is like this as well. Unlike English where we have count and non-count nouns (as you mention in your article), there are counters for everything and they are sometimes far from intuitive, nor is there always agreement as to their origin.

An often cited example of this is the use of “WA” to count rabbits. “WA” is meant to count birds, but it is also used for rabbits. There are several theories as to how this happened. One is that because the seem to fly when they hop, they looked like birds. Another is based on the way the were bundled together after they had been hunted, with their wing-like ears flopping around. Yet another is that monks wanted them classified that way so that they would be allowed to eat them, as they were not allowed to eat “meat” other than fowl.

I think it is important to approach the whole endeavor as a grand puzzle to be worked out over time and by trial and error. If you stick to it long enough, you will get it. It has taken me 25 years with Japanese, but it has been an adventure.

@Kurt, yes, you’re right! I always want to look for an explanation, but sometimes these things really are arbitrary.

I love the image of rabbits’ ears flapping like wings after they’re caught.

I’m loving this series Veronique! And looking forward to next week’s. Learning a second language is so like learning another way of thinking about most everything. It’s kind of dazzling.

@Sean glad you’re enjoying it! The series has been a rare pleasure to write.