I recently became familiar with a scientist whose productivity makes me exhausted: Georges-Louis Leclerc, the Count of Buffon, who produced a 36-volume work on natural history in the mid-18th century. Trained as a lawyer, he became interested in mathematics and then botany on his family’s lands in France. His work propelled him into a choice position as the curator of the royal botanical gardens—which included cataloging the natural history collection of Louis XV–and to writing his best-selling Natural History: General and Particular.

I recently became familiar with a scientist whose productivity makes me exhausted: Georges-Louis Leclerc, the Count of Buffon, who produced a 36-volume work on natural history in the mid-18th century. Trained as a lawyer, he became interested in mathematics and then botany on his family’s lands in France. His work propelled him into a choice position as the curator of the royal botanical gardens—which included cataloging the natural history collection of Louis XV–and to writing his best-selling Natural History: General and Particular.

The volumes covered everything from birds to minerals to the formation of the earth. European newspapers raved about it; Paris salons discussed it. It was the natural history book that could—how delightful it sounds to be in a time where you, your friends, and everyone you know is looking at pictures of the head structure of reptiles and talking about what would happen if you shot a musket-ball from a mountain top through the earth’s atmosphere.

Then he wrote about quadrupeds. To write about the four-legged creatures in the Americas, where he hadn’t been, Buffon relied on reports from travelers about the region’s inhabitants. His conclusion: the continents’ cold climates and humid swamps led to weaker, smaller animals, with only puny species in comparison to the majesty of Old World representatives like the elephant, lion, or tiger. Even animals that had been imported to the west fared poorly—dogs were mute, sheep were more skeletal (and less tasty)—the only domestic animal that seemed to do well, Buffon wrote, was the hog.

And this is where Buffon got in trouble with Thomas Jefferson. The result: a series of interactions that ended with a large dead moose on Buffon’s doorstep.

I learned all of this in the highly entertaining Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose, by University of Louisville biologist Lee Alan Dugatkin. It came out several years ago but caught me at the perfect moment, when I find myself with two obsessions—the founding fathers of the United States and the moose. (They go together like peanut butter and jelly, right?)

Buffon was not the only one who wrote about America’s pale comparison to other continents. The idea, known as the degeneracy theory, was also touted by other European intellectuals, and extended beyond quadrupeds to both the bipeds who first lived here and those who had left Europe to settle in the New World—they were thought to be lazy, corrupted, dull, and even “vegetative”.

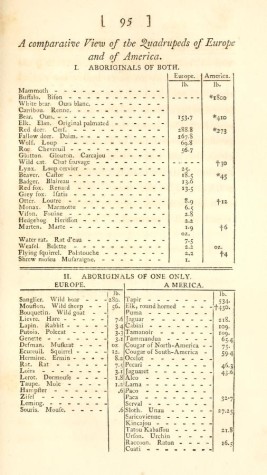

That didn’t sit so well with Jefferson and his compatriots, who worried, among other things, that no one would trade with the new United States if the country was so enfeebled. It particularly irked Thomas Jefferson, a lover of natural history–so much so that he published a response to Buffon in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, including charts with size comparisons between European and American quadrupeds.

Jefferson thought showing Buffon a moose would really seal the deal, but he didn’t know much about them. He sent out surveys to the people he corresponded with to learn more about the animal: what do they eat, how big are they, even whether “they make a loud ratling sound when they run?”

Through a series of complicated events, Jefferson ended up getting a dead moose shipped to France. The moose looked a little travel-worn when it arrived, but still, he had it delivered to Buffon.

Buffon never responded as Jefferson had hoped; he died six months later.

In the entrance hall of Monticello, there is a pair of moose antlers that measures 39 inches from tip to tip, likely acquired around the time of Jefferson’s moose quest. But the moose that Buffon received? Like the degeneracy theory, it seems to be lost to history.

**

Moose image by Kevin Dooley via Flickr/Creative Commons license

Table from Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia

One thought on “Ding Dong Moose”

Comments are closed.