Blacksmith Scene (1893), thought to be the first staged narrative in film

Last summer, after a decade in Canada’s Northwest Territories, I moved south to Ottawa. It is a city that holds deeper roots for me the longer I dig. Every day, I pass the park where my high school friends used to hang, and I pick up my son from an after-school program in the church where my parents were married.

Here, the experimental farm where my mother had her first summer job, picking strawberries. There, the yellow thing that has usurped the lot of my grandparents’ house. Its windowpanes have prominent Xs instead of + shapes. (Actually, maybe I like it.) We play at the beach in Britannia Bay, where my great-great-uncle drowned in a sailboat accident. His body was never recovered, so presumably he’s still there.

But there are clear familial voices from still further back – ones that blend with the ghost of another city in the same place. It wasn’t Ottawa in the early 1800s when my four-times-great-grandfather arrived from Montreal – it was a timber hub called Bytown, and Confederation was yet to bring Canada into being.

Bytown was divided socially into Lowertown, east of the Rideau Canal where oppressed French Canadians and Irish Catholics lived, and Uppertown where the ruling Scottish protestant elite lived. Though my Ottawa forefathers were originally Irish, their ancestors were Protestants from Tipperary – the site of a large British military barracks before the Irish War of Independence – so their place was deemed to be Uppertown.

My great-great-grandfather George Holland remembers participating in a teenaged raid on the stronghold of the Lowertown boys, “my brother and myself being ignominiously captured and taken home by an unsympathetic parent, who could not appreciate our desire for glory and our zeal for the cause of upper town.” Soon enough, at 19, he would get his chance with a real musket, resisting raids from the Fenian Brotherhood across the US border.

According to his memoirs, the great issues during his childhood were the Crimean War, the Mutiny in India, “panoramas of the trek of Joe Smith and his Mormons to the Great Salt Lake” and the Gold Rush in California. Nobody knew what tomatoes were. “The Indians played lacrosse on Barrack Hill, and we looked on with admiration and envy.”

“How many of us can remember when we used to have daguerreotypes taken at Lockwood’s gallery, near Sapper’s Bridge [now the Plaza Bridge east of the Parliament buildings]. It meant an exposure then from three to five minutes and the results were sometimes awful. I have some of those horrors yet. In another generation they will be worth their weight in Buffalo robes, to a photographer’s society.”

That’s my uncle Andrew talking (George’s brother). He goes on: “The marvels that we have seen since then are only an indication of what the present generation will see long before the year 2000.”

Obviously, that’s a safe bet for him to make, writing in the year 1903, but I can’t quite describe the feeling of reading a distant ancestor’s thoughts about the year 2000, the turn of which I spent on the roof of a theatre in Kyoto, Japan, having reached that country in less than a day’s journey.

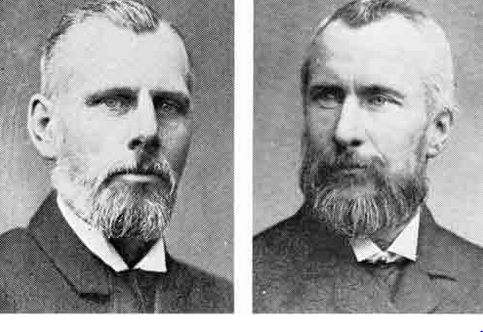

The Holland Brothers (George and Andrew) played an active role in the politics of the day, running the Daily Citizen newspaper (now The Ottawa Citizen) as a Conservative organ in support of their friend, John A. Macdonald (the first prime minister). George successfully talked Macdonald out of resigning the party leadership after a discouraging election, after which he went on to be Prime Minister again. But in essence I think the Holland Brothers’ hearts were always in tech.

Wherever the Hollands went, the new inventions of the time popped up. In 1892 they marketed phonographs — “the perfect stenographer!” — to federal government departments, then the Smith-Premier typewriter and the new technique of verbatim shorthand. They had a close affiliation with Thomas Edison, for some of whose inventions they were the exclusive Eastern US and Canadian agents. Edison had begun his career as a teenaged telegrapher in Stratford, Ontario and had a fondness for Canada.

In 1894, the first ten Kinetoscopes, or “peep show” machines, were delivered to Andrew who set up a parlour at 1155 Broadway in New York and at the Perley Building on Sparks Street in Ottawa. Patrons could pay their 10 cents to peer into shoulder-high contraptions and see some seconds of silent action – a boxing match, a ballerina dancing, a barber cutting hair. They showed the Blacksmith Scene (posted above) and this film of German strongman Eugen Sandow voguing:

Two years later when Edison manufactured the Vitascope — an improved version that could be projected onto a screen — the brothers Holland set it up in West End Park (now Fisher Park school on Holland Avenue). Twenty-five cents got you an audience seat and a tram ticket to get there. The silent films were accompanied by the Governor General’s Foot Guard Band, which seems like a strange accompaniment to their greatest hit: this rather repulsive 35-second film called The Kiss, which was part of a New York stage comedy starring May Irwin.

They also showed this presumably thrilling display of a Coney Island water ride:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uERSsS5E_x4

Footage of the Black Diamond Express:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–0axU7DDWQ

and this fancifully hand-coloured footage of Laloie Fuller’s Serpentine dance, which must be a first attempt at special effects.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fIrnFrDXjlk

A racially exploitative film called “Watermelon eating contest” also appeared, and I won’t link to it.

It’s odd to think that Ottawa was cutting edge in the film industry, and the lead didn’t last – perhaps because the Holland brothers put their energies elsewhere. Andrew sailed to Australia and helped set up the steamship line from Sydney to Vancouver. George started up the Hansard system of debate reporting in Canada and became Senate reporter for forty years. The brothers died in their late 70s, within a month of each other, but they left behind reams of their writing. One of these days I’ll sit down to read it.

All films in the public domain.

Hi Jessa, I was thrilled to find your page here. I am a history buff myself with family roots in the area going back before By Town. I am currently researching your forefathers and I have found much on the first picture show here in Ottawa but find your personal accounts of their youthful explorations and comments on the events of the day fascinating. The City Archives have biographical material on George but not much unfortunately on Andrew. I hope you post more on them in the future.

Great post! Thank you so much for sharing it.