Rounding a corner in Manhattan last week, I saw a handprint spray-painted on a wall. It was my hand. I had put it there last summer, my first and only piece of graffiti. It was nothing special, no artistic flair other than my five fingers. I had gloved my hand in plastic wrap and waved spray paint over it, creating a simple stencil out of part of my body, one of the oldest forms of enduring human expression.

The wall of the building had originally been a sprawling gallery of graffiti until, against the wishes of those living inside, the city whitewashed the whole thing. I was staying with one of the residents when the white-washing occurred. She invited me to go to the wall and plant a new seed. She was hoping graffiti artists would soon return and start the process again. A print was needed to kick off the next wave.

Last week, I was glad to see that the seed had taken hold. Several new images had sprung up.

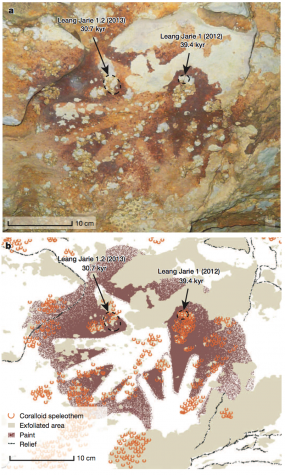

The oldest known rock art of a handprint was recently dated at 39,900 years ago in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The technique was more or less the same as mine. Wet pigment had been blown across and hand pressed against the rock to leave a negative impression.

Is there anything more indelible and primally human than the image of a handprint? The oldest print in the cave on Sulawesi is part of 12 prints painted at different times around images of animals. What was on their minds is hard to say, but it is a sentiment that is seen around the world. Other Paleolithic stencils of hands have been found throughout caves in Southern France, the oldest in Chauvet Cave dating to 31,000 years ago. El Castillo Cave in Spain has handprint stencils in red ochre dating to 37,300 years ago. From Indonesia to Europe, give or take 10,000 years, people were leaving the same expression.

I’ve seen this sort of imagery on rock faces and in sheltered alcoves across the American Southwest where dates range to the last few thousand years. Seeking shade in the summer in the desert of Southeast Utah, I crawled into a low rock overhang. On the ceiling were at least 40 handprint stencils made in the same fashion. These were adults and children, some fingers long and slender like those of piano players, some meaty like fieldworkers and masons. I lay on my back looking up at the arrays of personalities, each a different individual. I wondered if this was a tally of those who lived here, a telling of some agreement, a prehistoric constitution signed by the people of this canyon system, or if it was a celebratory gathering.

A study of caves in France found that the majority of the Paleolithic prints are arguable female. Women tend to have ring and index fingers of about the same length, whereas men’s ring fingers tend to be longer than their index fingers. This pattern revealed that 3/4 of the painted prints in the region came from women. The social differences between genders tens of thousands of years ago may have had nothing to do with divisions we see now. There is no way of knowing their intentions or why exactly prints came to be on these hidden walls, but the ultimate impetus may have been the same as mine. Beyond gender and culture, we keep doing the same thing, pressing our hands to some surface and leaving a mark as if to say, we were here.

The drive to leave this five-fingered print is not something I can consciously explain. We’ve been doing exactly this across vast geographies since the beginning of our own time. These are perhaps the marks of the first journalists, the first story-tellers that wanted more than words to pierce through time. I hadn’t placed it on the wall out of some homage to the past, but because I looked at the tools at my disposal and it seemed like the quickest and easiest way for an amateur to leave a mark without getting caught.

I’m not a fan of modern graffiti in the backcountry or natural settings, but in the city I feel as if I am in a labyrinthine cave. Under the green torch of a streetlight, I gave my story, a simple narrative, the cleanest, oldest story I could ever tell.

Top image shutterstock. Second image from the Nature article, Pleistocene cave art from Sulawesi, Indonesia, October 2014. Third from me last week.

We can’t know for sure, but I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest that those somewhat ancient handprints were left because of a consensus amongst the community members that it was a good thing. Among other things, it is also likely that no one person “owned” the cave in which those were deposited. And so, these many thousands of years later, we marvel at these artistic endeavors.

Today, society generally rejects the placement of “art” on the walls of buildings that are not the property of the “artist.” What might have been the clue that this “art” wasn’t appreciated by the masses? Perhaps it was fact that the city whitewashed the graffiti that had been previously deposited by a multitude of individual “artists.”

Now, if you had truly believed that spraying paint was some sort of “expression” of artistic merit, you should not have wrapped you hand in plastic. Spraying your hand along with the wall would have been so much better. Just think. When anyone asked why your hand was covered in paint you could tell them all about the wonderful contribution you had made to the aesthetics of the city. As well, you could explain how you artfully convinced the building’s owner that it would be a good thing. You did contact the owner didn’t you?