Two nights ago I sat in a theater watching the film “The Martian.” I loved seeing a viable spacecraft making gravitational slingshots around planets while a stranded, potato-growing astronaut claimed himself the first colonist on Mars.

Two nights ago I sat in a theater watching the film “The Martian.” I loved seeing a viable spacecraft making gravitational slingshots around planets while a stranded, potato-growing astronaut claimed himself the first colonist on Mars.

What’s there not to love?

Meanwhile, in my coat pocket I carried an object from an entirely different age of colonization.

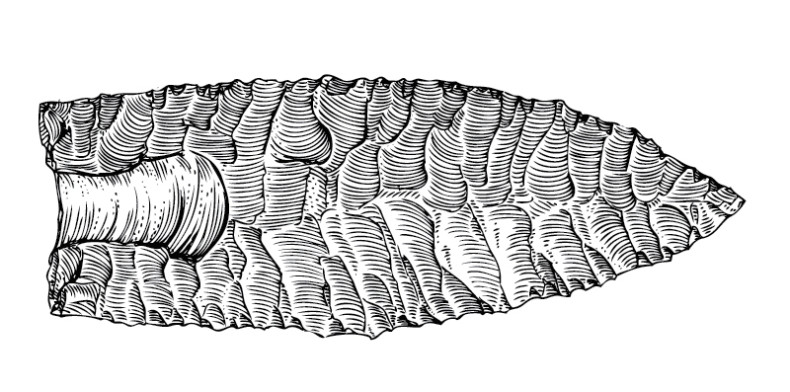

I had just spent three days with flint knapper Greg Nunn in Utah. I had commissioned Nunn to make a replica of a Clovis-era spear point, a megafauna hunting tool from the American Paleolithic. I had put the rocket-shaped artifact — the length of my hand from wrist to fingertip — in my pocket and forgot it was there until I walked out of the theater. Reaching in, I found the sharp-edged stone and pulled it out.

Like everything I had just watched, the Clovis point was the height of technology for its time. It was a tool being carried into an unknown land 13,000 years ago. As thin as a letter envelope and long enough to glide into the heart or lungs of a mammoth or Pleistocene bison, the Clovis point was a tool of colonization. It was a landing module on Mars.

Greg Nunn is a renowned replicator of ancient stone tools. He is often called into archaeological sites to look at artifacts, and from them he has cracked the codes of their original techniques. I had gone to him to understand the procedures for making one of the most complex pieces of technology for its time. He started with a big nodule of chert and worked it from above and below until it began to resemble a teardrop.

Meanwhile, in “The Martian,” engineers from the Jet Propulsion Lab sweated out their calculations while astronauts used all the brain power they could muster trying to intercept their stranded companion. Perhaps I saw a similar deftness in Nunn.

Nunn employed only original tools, the butt of red deer antler for its softness and flexibility, billet of moose antler for its hardness. He had a row of hammerstones lined up on a cottonwood log, each the size of a doorknob, selected for their weight, grain and shape. For three days I listened to his blows against different pieces of chert. It was the music of a different age.

Pieces that came off cleanly like he planned were shaped like angelfish. Nunn reached down and picked up the best ones, fitting them back into place to admire the ease with which they flew.

He struck with a cobble and didn’t get the flake he wanted, just a puff of impact dust, smell of ozone.

“You can hear the difference, your ears are as much a tool as anything,” he said.

He took another swing and the impact sounded like a hunk of steel.

“You hear that,” he said. “It was dull, not as sharp.” He struck again and again, listening to tones. Third strike, the stone rang like crystal and another angelfish popped off the back. He picked up the piece and fit it back in place. “I could have drawn that with a pencil,” he said.

Have we gotten smarter since the Ice Age, or have we just changed focus?

When the stranded astronaut Mark Watney, played by Matt Damon, said, “I’m gonna have to science the shit out of this,” he might have meant something like Nunn working for three days puzzling out a tool that would have been utterly useless to a person stuck on Mars.

As far as brain size, we aren’t much different now than we were then. Our brains are slightly smaller than they were in the Paloolithic. The largest Homo sapiens lived 20,000 to 30,000 years ago with an average weight between 176 and 188 pounds and a brain size of 1,500 cubic centimeters, 150 cc’s larger than our modern average. It’s hard to say what was lost between then and now.

Our brains may have become more efficiently and densely packed. This may be related to our fealty to unseen agents such as societies and institutions. The parts of the brain operating in abstraction, relating to the unseen, are small and concentrated. The angular gyrus located in the back left side of the human brain is a semantic processing organ that controls reading, number processing, the retrieval of memory, spatial cognition, reasoning, and social cognition. It is the size of a couple grapes.

We now look at large spatial navigation as a mathematical problem, not a tactile one. This has allowed us to slingshot probes around the gravity wells of other planets. In August of 2012, our first probe still in communication, Voyager 1, passed beyond the sun’s solar winds and entered interstellar space, the first relay we’ve gotten that far out. The mental acuity required to find a way through mountain ranges and glaciers populated with mammoths and giant bears is not needed as much any more.

When Clovis points came into vogue, they were part of what appears to have been the first widespread settlement of North America approximately 13,000 years ago. Alhough humans had definitely arrived on the continent earlier, this is a big continent. They would have still been finding mostly undiscovered places.

When Clovis points came into vogue, they were part of what appears to have been the first widespread settlement of North America approximately 13,000 years ago. Alhough humans had definitely arrived on the continent earlier, this is a big continent. They would have still been finding mostly undiscovered places.

In the film (and the book), Watney said, “It’s a strange feeling. Everywhere I go, I’m the first. Step outside the rover? First guy ever to be there! Climb a hill? First guy to climb that hill! Kick a rock? That rock hadn’t moved in a million years! I’m the first guy to drive long-distance on Mars. The first guy to spend more than thirty-one sols on Mars. The first guy to grow crops on Mars. First, first, first!”

It must have been a strange feeling in the Paleolithic, too.

When I pulled the point from my pocket outside the theater, snow was coming down hard. The dark and sharply fashioned chert held enough warmth from my body that every snowflake that touched it melted. I was for a moment balanced between two different eras of colonization and technology. Holding the rock on my hand, the distance between the two did not seem so far. We are still doing the same thing, charging ahead with all our intellect and skill and hoping for the best.

Images: 20th Century Fox and Shutterstock.

One thought on ““The Martian” and Ice Age Astronauts”

Comments are closed.