Investigative journalists seem awfully glamorous – delving into mysteries and catching those liars at their game. Unfortunately, I don’t have any of the aptitudes involved, so I steer clear of it. But recently I’ve had the thrill of that hunt in miniature.

Investigative journalists seem awfully glamorous – delving into mysteries and catching those liars at their game. Unfortunately, I don’t have any of the aptitudes involved, so I steer clear of it. But recently I’ve had the thrill of that hunt in miniature.

It all began when an editor sent me a link to the check above, to illustrate an assignment about in-kind payment. Newfoundland was the last colony to join Canadian confederation (in 1949) and before it did, there was a currency shortage, so people kept credit accounts in the form of their primary export: cod.

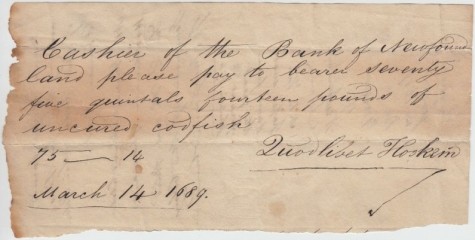

The text of this check, if you can’t make it out, reads as follows:

Cashier of the Bank of Newfound land please pay to bearer seventy five quintals fourteen pounds of uncured codfish 75—14

Quodlibet Hookem (Hoskem? Hoskim?)

March 14 1689

A quintal was 112 pounds of cod. On the website Newfoundlandia.com, it is labeled “1689 Codfish Currency Cheque” and will go to anyone who wants to pay CAD$275. “Overall well-preserved, with some foxing, folds and irregular edge of the paper.”

The part of this check that stood out to me was the word “uncured”. Fresh fish as you may know, doesn’t keep. To put it like a Newfoundlander, it gets “maggoty”. So when I talked to historian Jeff Webb at Memorial University in Newfoundland, I mentioned the image. “That sounds like a mistake,” he said. “It was always salted.”

The salt draws out the water from inside the fish and keeps it from rotting. Undeterred, I followed up on the interview and sent Webb the image:

“I thought you might be interested in the artifact below — the uncured fish cheque we discussed, routed through the Bank of Newfoundland. Presumably this is more rare than orders of salted cod.”

He wrote back:

That is very curious. I don’t know what the “bank of Newfoundland” would have

been, especially in the seventeenth century. I’m going to ask a friend about

that.”

Then he confirmed:

There never was a “Bank of Newfoundland” and there were few residents on the island in 1689. Newfoundland didn’t have much in the way of financial institutions until the nineteenth century.

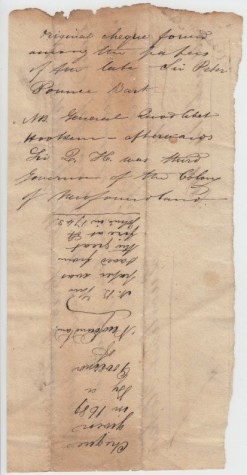

Hmm. Here I start to feel a little silly, but I return to the object in question and see that Webb may have missed something key about the cheque’s provenance. On the back of the paper are two notes. Here is the first:

It reads: “Original cheque found among the papers of late Sir Peter Pounce Bart. N.B. General Quodlibet Hookem. Afterwards, Sir Q.H. was third Governor of the Colony of Newfoundland.

Aha! Perhaps this is the key to the misunderstanding. If the cheque writer was a Governor of Newfoundland, then maybe he could draw on whatever treasury existed for the government, which he might refer to as the “Bank of Newfoundland”. Not unreasonable. But our friend Quodlibet is nowhere to be found in the list of Proprietary Governors of the colony.

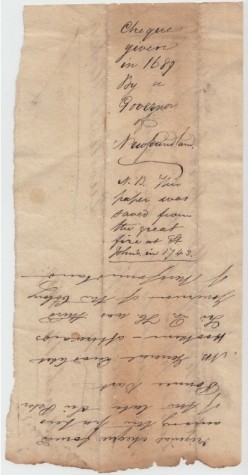

Here it is again upside down:

This way up, the note says:

“Cheque given in 1689 by a governor of Newfoundland. N.B. This paper was saved from the great fire at St. John’s in 1743.”

Nope, there were a few big fires in Newfoundland, but 1743 doesn’t seem to be one of them.

Then another email from Webb, who’s getting into it too, now.

A colleague confirms my feeling that the handwriting does not look like 17th-Century hand. And the name on the signature “quodlibits” is a word that means fanciful text. Without any other evidence I believe it is most likely a hoax.

Wow. A trickster went to the trouble to create a forgery? I look up “Peter Pounce”, among whose papers it allegedly was found, and which sounds like another fanciful name. Sure enough, that’s a character in a 1741 Henry Fielding novel – one of the first novels in the English language. The thing about this hoax is that I feel like a fool even writing about it, for fear that it was blindingly obvious from the start to you, Gentle Reader.

At this point, it was time to take a closer look at the website selling this thing, Newfoundlandia.com. It’s not an extensive collection, and none of the other objects look particularly suspect. Everything’s reasonably priced. $275 doesn’t seem like a king’s ransom worth risking much for, especially now that the Canadian dollar has tanked. And if the site is some kind of society for creative anachronisms, it’s very understated.

I am burning to know the provenance of this thing, so I reverse look up the contact number for the site and find it belongs to a Dr. O’Connor in British Columbia who served his residency in Newfoundland and practiced in a remote outport fishing town there for a while. I give him a call.

Dr. O’Connor mumbles very quickly, but it soon becomes apparent he isn’t going to further the matter, even to the point of putting a caveat on the website. He doesn’t remember who he got the check from — it’s in a box somewhere, but he doesn’t have time to look. He compares the artifact to the Shroud of Turin, in that even if it’s not the real thing, it’s old and therefore interesting. (Here we agree.)

O’Connor maintains, though, that we can’t know whether it is an authentic financial document or not. That the history of Newfoundland from 1600 – 1800 is a black box because of fires and destruction by the French. (An assertion like that, to me, is super spurious — absolutely nothing about this thing checks out.) And if the explanation on the back is apocryphal, he adds, it could have been an honest mistake: the story that had always been told by someone’s grandfather.

Perhaps I have to accept that history is not a science, and that some things are unknowable. Still, I am loath to let this one go. Somewhere out there is the real story of this tall tale.

Yay, a riddle! Here is my guess:

From Wikipedia, the origin of quodlibet is ” Latin for “what pleases” from quod, “what” and lībō, “to taste”).

Hookem – Hook them?

Could the “bank of Newfoundland” refer to the Grand Banks?

In other words, is this check a little joke meaning, “there is cod in the ocean if it pleases you to catch it”?

Becky that’s amazing. I am overwhelmed by your ingenuity!