Right now, parents newly versed in the vocabulary of doom are discussing the Cascadia subduction in Seattle backyards, in Portland parks. They’ve read the recent New Yorker article about the devastating earthquake overdue in the Pacific Northwest. Maybe they’ve also read the stories in Outside and Discover. They know that three thousand schools around the region could collapse in the quake and that kids on the coast will be trapped in their elementary schools by the tsunami that follows.

Right now, parents newly versed in the vocabulary of doom are discussing the Cascadia subduction in Seattle backyards, in Portland parks. They’ve read the recent New Yorker article about the devastating earthquake overdue in the Pacific Northwest. Maybe they’ve also read the stories in Outside and Discover. They know that three thousand schools around the region could collapse in the quake and that kids on the coast will be trapped in their elementary schools by the tsunami that follows.

Right now, their kids, playing among the rhododendron, are overhearing this conversation. Some will ignore it; by silent consensus, they’ll move their wild games farther away. But some kids will creep closer, hoping to remain unnoticed so the grown-ups will keep talking. These are the ones prone to catastrophizing, who are always attuned to a hint of apocalypse, who have been freaking out about climate change perhaps too much. These are the magical thinkers, the worriers. I know these kids; I once was one of them.

I grew up in Santa Monica in the 1970s and 80s under blue sky and under the threat of what we referred to only as The Big One, the inevitable mawing of the San Andreas Fault. I don’t remember when I learned that I lived on a faultline, or that the ocean, which was a mile and a half from my bedroom, would rear up and swallow anyone on its shore. I only remember always having knowledge of the earthquake. I only remember trying to stop it.

I loved the ocean and I was terrified that I would be killed by the ocean, a dualism that has continued in my adult relationship with nature. I loved the ocean precisely for its wildness, for all the ways it wasn’t a swimming pool. I loved the stink of seaweed and the thrash of the waves. I loved the reach of horizon. I loved the narcotizing effect of sun against sand. My father also loved the ocean for these reasons, and because he could sit on a folding chair grading papers for hours while his three daughters mostly ignored him. My mother hated the beach. And so, on summer days and weekends, my dad would bike with us to the Pacific Coast Highway and lead us through a rank tunnel and onto the sand.

The days were relaxed, but I wasn’t, at least not at first. Not until I’d performed my three tasks to still the earth. First, even before I put on my bathing suit, I devoted an hour to worrying that the earthquake would hit while we were at the beach. (Worrying is a crucial preventative ritual of magical thinkers. Sometimes we worry that we’re not worrying enough.) Second, just before we left, I’d stand in the doorway of my mom’s bedroom and ask if there’d be a tsunami that day. She would say, no, not today. This was our script. Finally, once I arrived at the beach, I’d search out cigarette butts and bring them to a trashcan plastered with an ad for Coppertone, that lewdly menacing illustration of a black dog pulling down the bathing suit bottom of a little girl. The trashcans smelled. Flies hovered. Before I could play, I threw in the butts to stop the tsunami.

If you’re wondering why the big one never happened between 1977 and 1987, you could ask a geologist. Or you could thank me. Oh, it was worth it, I’d say modestly.

During those years I often recited to myself lines from two poems I’d memorized over a week in first grade when I stayed home with chickenpox and my mom handed me a book of Robert Frost. The first was “Fire and Ice” which fascinated me because it admitted that the end of the world was a certainty —Some say the world will end in fire,/ Some say in ice — and yet its tone was sanguine. I thought obsessively and privately about whether the world would end by nuclear war or by earthquake, but I never imagined that anyone joked about such things. The second poem I memorized was “The Road Not Taken.” Two roads diverged in a yellow wood. This poem is irresistible for its meter, but it was the last sentence that fascinated me.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

I didn’t interpret this oft-quoted ending as inspirational. I read it as a warning, ominous. Any decision, it seemed to suggest, even the decision to bike to the beach on a sunny summer day, might make all the difference. Over time, the messages I took from these two poems blended together in a kind of dialogue: Catastrophe. Choice. Catastrophe. Choice. The world would end and my decision would make all the difference.

Right now, I imagine, some kids in Pacific Northwest are forming rituals of their own to stop the end of the world, to counter uncertainty, to master an unmasterable situation. I’ve been trying to decide what I would tell these kids. Would I reassure, promise daily that today won’t be the day? Would I minimize the concern, point out gaps in scientific knowledge, the limits of probability? Would I try to convince that we each are, in fact, without power over the shifting of land masses, that nothing we do will change anything? Would I lie and say that I’m not frightened, modeling a healthy denial?

I’m not sure. I’ve learned that there are few words that can reassure a mind bent on worrying about catastrophe.

The only thing I know is that I’d take them to the ocean. More than explanations or reassurances, It was the place that frightened me that ultimately calmed me. It still does. The waves can counter my grandiosity with their grandeur. The gusts of sand flies, the seagulls and half-chewed crabs and occasional arcs of dolphins — all this distracts me. The wildness of the sea returns me to my small size.

I felt neither relief or victory at the end of my childhood beach days, when we finally biked away from the inundation zone. I’d forgotten all about the tsunami by then. I was sunned and tired and lulled. I was happy. Two roads had diverged in a yellow wood, and it hadn’t mattered at all which one I’d chosen.

Heather Abel is the author of the Kindle Single Gut Instincts: Dispatches from the Wide Open Space Between Sickness and Health. Her debut novel, THE PRESERVATION OF THE WORLD, will be published by Algonquin in 2017. She can be found on twitter.

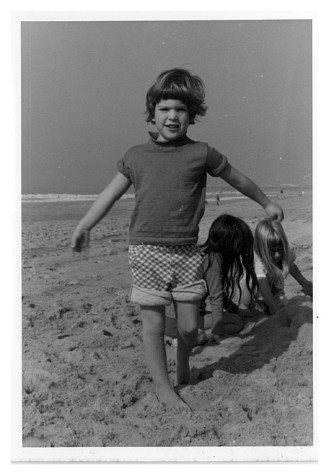

Photo of author looking worried at the beach is by her mother.

Beautiful piece.