“I have an idea,” said my friend Chris. We often walk and talk briskly together in the California beach town where we live. Not long before, we’d talked about how the Earth’s huge population is a major contributor to global warming. So I was only slightly amazed when she followed up with, “I think we should write to the pope.”

Although Vatican City has no families and a fertility rate of zero children per family, the Catholic Church opposes contraception. As leader of the Church, the pope has the power to make women half a world away bear children they do not want and which the world does not need. Would it do any good to ask him to change that policy? I wasn’t convinced. But I loved the idea of writing a letter that might move a pontiff and help save the world.

I knew the Vatican of the last few decades cared about science, accepting evolution and the Big Bang, for example, and sheepishly forgiving Galileo in 1992 (it takes guts to admit you were wrong). And the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, in the Casina Pio IV (shown above), looks like a great place for a sabbatical.

Chris wrote up a draft of a letter to His Holiness, tactfully pointing out that the Catholic Church has a pivotal role to play in solving the problem of global warming. I added facts, references, and polish.

We had plenty of time. Our deadline was the encyclical on climate change to be released in the summer of 2015. That was a year away, a balmy summer and a dry winter away.

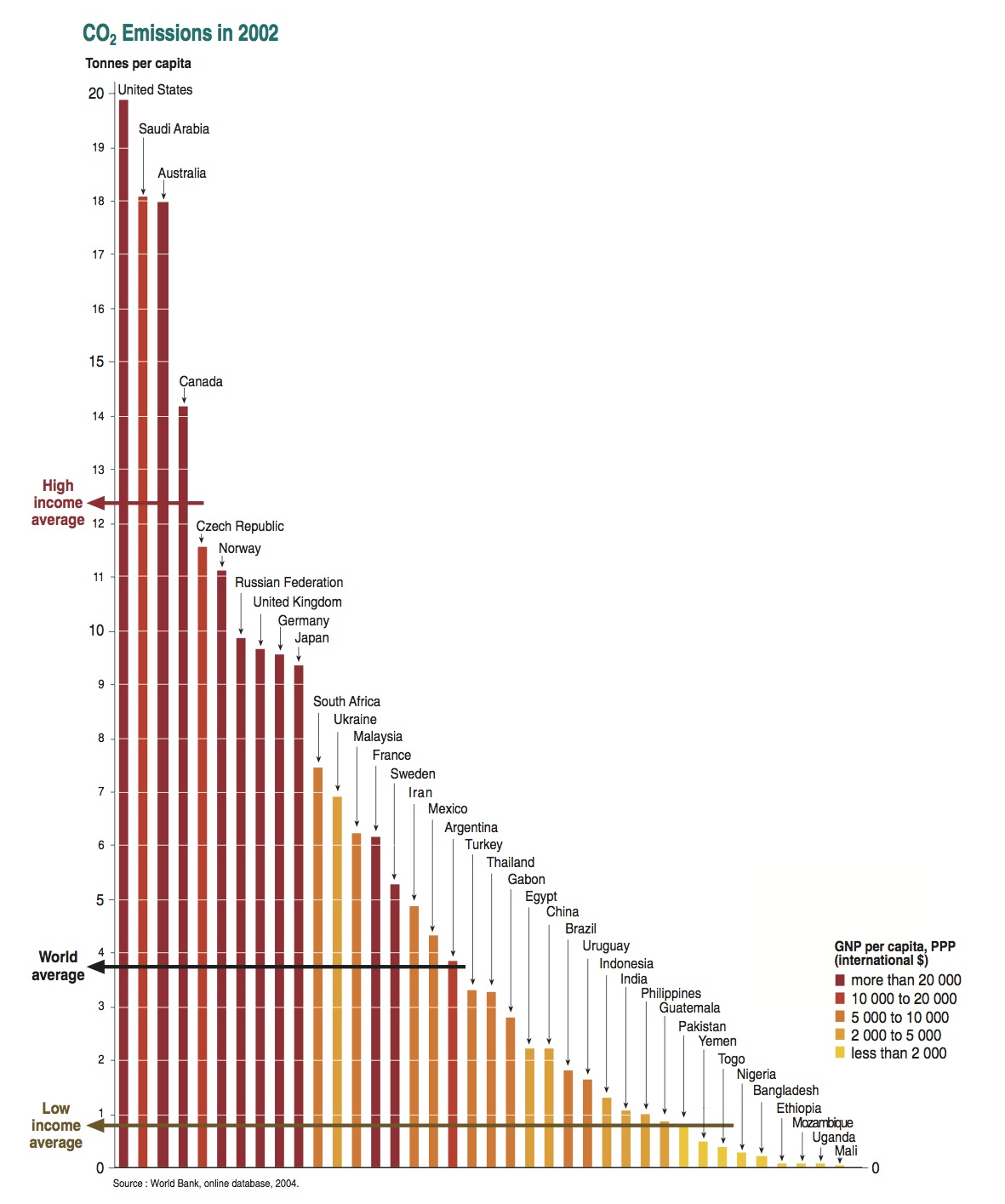

Our lives were comfortable, so why did we think we needed to save the world? To avoid global disaster, a growing consensus of scientists believe, we should reduce our carbon emissions as fast as possible. The average person living on Earth has a carbon footprint of about four metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. We need to drive that per capita number down to basically zero, through conservation and a massive build up of renewable energy.

But even if we halved the global average, multiply that number by 6 billion, 7 billion, and, right around the corner, 8 billion people, and it will still be a huge number. In the long term, becoming fewer would make a huge difference. But in the short term—like next year—the effect is nil. It can seem less important, even unimportant.

And even among the greenest of liberals the “p” word is fraught. “I wouldn’t want anyone to tell me how many children I could have,” said an acquaintance who is childless by choice. “We just need to educate women,” says another. “The problem is people in [insert developing region here] who have so many children.” Please don’t make me think about this, their eyes say.

And, anyway, even if our absolute numbers are still going up, they’re not going up as fast as before. If we do nothing, the problem will solve itself, right?

We’re almost out of gas; why brake?

Except it’s not. Even with a rate of increase of only 1.14 percent per year, our global population is growing at the rate of about 83 million more people a year.

Pope Francis could help. Like no other recent pope, he has the attention of the whole world, both Catholic and non-Catholic. Because of the Church’s work providing health care throughout the world, he can make it possible for millions more people to gain access to contraceptives and he can make it acceptable for people who want to use them to do so.

This pope had shown a remarkable concern for the environment, so although it was a long shot, maybe our kernel of an idea would land in fertile ground. In July, 2014, he visited Italy’s University of Molise and observed:

“I fully agree with what was said about ‘safeguarding’ the land, so it may bear fruit without being ‘exploited.’ This is one of the greatest challenges of our time: changing to a form of development that seeks to respect creation. I see America—my homeland, too: many forests stripped, which become land that cannot be cultivated, which cannot give life. This is our sin: exploiting the land and not allowing it to give us what it has within it, with our help through cultivation.”

I was heartened. Maybe Chris and I just needed to persuade him that the natural expression of his concern is to address birth control, and therefore population. In an early draft, I tried to explain about Earth’s carrying capacity without getting too technical. But it didn’t seem right to lecture him. I tried to keep things short, tried to speak his language: “Our numbers burden creation,” I wrote.

A friend asked why we were writing to the pope. Were we picking on Catholics? Not at all. Pope Francis has said climate change is something we ourselves inflicted on the Earth; he is listening and willing to talk about what that means for us—what we can do. And he has a moral authority few other people in the world have. We weren’t asking him to speak only for or to Catholics, but for all of us. And, more concretely, we hoped he would find a way to reverse the Church’s opposition to contraception.

Another friend wondered why we didn’t support the education of girls and women and back away from talking about contraception and families. She urged us to temper our arguments, make them vaguer and more circumspect.

Chris and I talked it over. Of course, we both believe in the education of women. But literacy isn’t a contraceptive. And let’s face it, one of the biggest barriers to access to contraceptives is the Catholic Church. The Church has the means and will to do enormous good, opening and funding health clinics in places of dire need, managing 26 percent of all the clinics in the world. But health clinics funded by the Church don’t offer contraceptives, giving the Church the power to keep contraceptives at bay even in communities where many are not Catholic.

Still, I toned down the letter, fuzzing the message. Don’t ask for what you can’t get. But the letter lost its focus, and Chris and I lost momentum and enthusiasm. Were we wrong to write to the pope at all? Were we wrong in our approach? We had work and then holidays. We skipped walks and didn’t see each other for weeks at a time.

The pope was often in the news, though, and, I couldn’t help but notice, making increasingly strong comments about climate change. He even addressed population! It came in January, when he traveled to the Philippines—densely populated, rapidly growing, and critically vulnerable to climate change. Already, thousands had been killed when Typhoon Haiyan struck the islands in 2013. The country had recently passed a law allowing the government to distribute free birth control pills and condoms, and although Pope Francis vaguely criticized the law during his visit, he also argued that the Church’s ban on contraception does not mean that women need to bear child after child. Instead, he advocated “responsible parenthood,” arguing that women who have more children that they can care for are irresponsible.

And then came the appalling kicker, “God gives you methods to be responsible. Some think that—excuse the word—that in order to be good Catholics we have to be like rabbits. No.”

Okay, that was really offensive. The contraceptive methods that work best are all banned by the Church, leaving only one, or two if you count abstinence, neither of which work well at all. And why is it only women who are blamed for having too many children? I was really annoyed with the pope! He was showing his true colors—those of a guy who has never really had to come to grips with the messy realities of reproduction.

But I could also see the silver lining. He was conceding that there’s such a thing as too many kids. This was big. Really big! I wanted to hug him, or at least kiss his papal ring or something.

I returned to the letter. If there was a chance that the pope already agreed with us, we should strengthen our arguments, not weaken them. I revised again and now I liked the letter. It felt right. Another writer friend read it and suggested changes. She offered to sign it, too. But I still didn’t send it. I thought maybe we should get more signatures.

I was pope googling near the end of May when I saw a date. The encyclical was June 18th! I hadn’t sent the letter! I’d thought I had another month or even two. Now there would be no time for him to respond to our thoughts. And by now I’d figured out that he would probably never even see it. He gets thousands of letters and, naturally, others scan these, reading for the very few that might interest him. He’s been known to call people who have written to him. He says, “This is the Pope.” Quite often they hang up on him because they naturally assume it’s a prank call. He calls back until they talk to him. This is the pope with a sense of humor.

I accepted that he probably wouldn’t see it. But someone at the Vatican would. Maybe it would push someone to do something, to say something, to show it to one other person. I tried to figure out how to send the letter as quickly as possible.

Email was out. For a short period, when the pope had an email address, the influx of letters crashed the Vatican servers. There was, however, a Vatican Communications office email address where you could supposedly write. I emailed the letter there; it bounced.

If I was going to use snail mail, I needed to turbocharge the snail. I looked for a full service FedEx location in Rome. I would email them the letter and they would print it out and then deliver it to Vatican City. Strangely, FedEx’s website didn’t show me any locations in Rome, or anywhere in Italy. So I FedExed the letter—two sheets of paper—half way round the world. I mourned the carbon footprint of that letter. At home I tracked its wanderings—from a tiny office in Soquel, California, to Memphis, then to Paris and finally, on a Sunday afternoon, to Lonate Pozzo, at the airport near Milan. I let Chris know it was in Italy. The next day, FedEx told us it had arrived at the Vatican.

Praised be.

_________

Jennie Dusheck is a California freelance science writer, who writes about all things biological, occasionally in guest posts for LWON. She can rant about biomedical topics, but her heart belongs to the furry and the feathered, the scaly and sublime. Facebook, LinkedIn

________

Photos: Casina Pio IV, Vatican City; GRID/Arendal; from the movie Thelma and Louise;

Good for you, Jennie and Chris! I hope I was not the friend that asked you to temper your arguments, because I remember suggesting that instead of asking the Pope to approve contraceptives outright you ask him to meet with knowledgeable women about it, because of the symbolic power of such a meeting. Anyway, everything you and Chris have done is positive for the world and I support you completely. Thank you!

Italy has one of the lowest birthrates in the world, despite the catholic church.

Scientists lack consensus on a target/goal world population at a given standard of living. Without a goal how do we have a meaningful discussion on reducing world population and its impact on climate change? How do we come up with plans and strategies? Pope Francis has opened the door to the discussion with his “Laudato Si’ On Care for Our Common Home”. How far will this go?

Catholicism* is a religion with many rules and dogmas and severe penalties for violations. Beyond abstinence and rhythm, birth control and abortion are not permitted. Yet in most developed countries (including Italy), Catholics practice multiple forms of birth control, violating the rules. Interestingly, the highest birth rate in the U.S. is among Mormons (recently published stat in NY Times). The point of this letter to the Pope was not to call out Catholics about reproduction, but rather to ask the Pope to exercise his moral leadership and popularity to address the impact of world population on climate change.

*I was raised Catholic and educated in Catholic schools, although I now identify as “religious dysphoric” (to borrow a term from the trans community).