My fascination with bears began on a family road trip from Wisconsin to Yellowstone. To pass the time, my parents and I took turns reading from a book whose title now escapes me. Was it “Bear Attacks”? Or “When Man Becomes Prey”? Well, you get the gist. It was gruesome and terrifying, a delicious read when one is safely tucked inside a moving vehicle. But later, alone in my tent with only a thin sheet of nylon between me and the bear-ridden blackness, the most devastating passages came back to haunt me.

I’m no idiot. I didn’t bring any food into the tent. But my pants, no doubt infused with the heady scent of hot dogs and toasted marshmallows, lay wadded near the flap. So I worried. My ears strained to hear everything—every creak, every snuffle, every twig snap. Even the tiniest noises echoed through the still air like the crack of a gunshot. Near dawn I drifted into a fitful sleep punctuated by dreams of bear maulings.

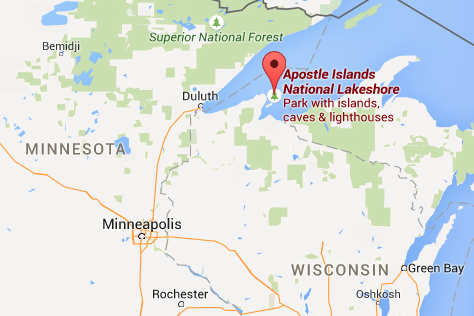

I never encountered a bear that trip. But last summer when I visited the Apostle Islands, an archipelago that juts out from Wisconsin’s northernmost tip into the deep blue of Lake Superior, memories of that terrifying book flooded back. My husband and I had reserved an idyllic and isolated campsite on Sand Island, part of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. We planned to kayak there. For weeks I had been nervous about the kayaking. Lake Superior is cold, and I am woefully inexperienced. But as I read up on the islands, a new worry emerged: The Apostle Islands are positively riddled with black bears.

According to the National Park Service, Stockton Island, a blip of land that covers less than 16 square miles, housed 31 bears in the mid-1990s, making it one of the most bear-dense spaces in North America. But the island bears are a transient bunch, and by 2010, the Stockton bear population had fallen to just 13. Meanwhile, on Oak Island, which is about a third of the size of Stockton, rangers counted 18 bears in 2010. And on Sand Island, which is smaller still, the tally was ten. To count the bears, researchers set up barbed wire enclosures and baited them with a rotten log laced with fish oil. When the bears came to investigate, they left a little hair stuck to the wire barbs. DNA analysis revealed the number of individual bears on each island as well as their sex.

According to the National Park Service, Stockton Island, a blip of land that covers less than 16 square miles, housed 31 bears in the mid-1990s, making it one of the most bear-dense spaces in North America. But the island bears are a transient bunch, and by 2010, the Stockton bear population had fallen to just 13. Meanwhile, on Oak Island, which is about a third of the size of Stockton, rangers counted 18 bears in 2010. And on Sand Island, which is smaller still, the tally was ten. To count the bears, researchers set up barbed wire enclosures and baited them with a rotten log laced with fish oil. When the bears came to investigate, they left a little hair stuck to the wire barbs. DNA analysis revealed the number of individual bears on each island as well as their sex.

I knew, of course, that bears populate Wisconsin’s heavily wooded north. And I guess I knew that bears could swim. But the idea that bears—so many of them!—would choose to take up residence on this tiny cluster of islands came as a shock.

Small populations of animals living on islands tend to rapidly lose genetic variability. But the Apostle Island bears seem to have avoided this fate. In a 2005 study, researchers found genetic variability comparable to other bear populations, which suggests a high rate of immigration from the mainland. The bears also seem willing to island hop. A 2010 study tracked one female bear that had Sand Island ancestry, was captured on Basswood Island, bred with a male from Oak Island, and gave birth on Hermit Island.

The high density of bears has caused other problems, however. In 2008, the National Park Service temporarily closed Manitou Island after a 200-pound bear backed a park volunteer into an outhouse and then laid down in front of the door, blocking escape. That same bear later developed a taste for Spam. “The Spam came from park visitors who not only had bad taste, but violated good sense as well as park regulations, and were long gone before we could find out who they were,” writes Bob Krumenaker, superintendent of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. “Bears are smart, so a single visitor not doing the right thing with food can corrupt a bear for a season.”

In 2013, rangers had to close Sand Island after a bear raided one tent and poked his head inside another, this one inhabited by people. The final straw came when a bear (the same bear, or perhaps a co-conspirator) stole sausages from a cooler on board a beached boat.

Troublemaking wildlife are often destroyed, but that approach doesn’t appeal to Krumenaker or his colleagues. Like therapists, they prefer to work on behavior change. “We’re the visitors to his home, so we will continue to give him the benefit of the doubt unless his behavior changes for the worse. And even then, we’ll close the island indefinitely unless he’s actually exhibited threatening behavior,” Krumenaker writes. “I’d rather take the heat for closing part of the park to people than kill a bear whose ‘guilt’ is the result of the temptation people have created for him.”

The Apostle Island bears may be numerous, but human-bear conflicts are relatively rare. The bears tend to be timid and wary of humans. I didn’t even catch a glimpse of one. And now that I’m in the safety of my office, I kind of wish I had.

****

Bear images courtesy of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

Map via Google

I have always thought of black bears as cute, harmless creatures. But I heard recently that they are more dangerous than grizzlies because of frequent human contact.

Really, Erik? But that seems like a strange way to measure dangerousness, doesn’t it? So would that mean that dogs are more dangerous than black bears because of an even greater frequency of contact? Surely more people get bit by dogs than get mauled by bears.