I met Jonathan Waldman when we were both magazine interns. We had a lot in common–we both got really into working on the magazine’s science column, and we were both really big fans of burritos. (He later sold me a shirt that featured a burrito-powered bike). When I ran into him at a conference a few years ago, he told me about his old sailboat, Syzygy. The boat had been totally rusty, he said–and it had given him an idea for a book.

I met Jonathan Waldman when we were both magazine interns. We had a lot in common–we both got really into working on the magazine’s science column, and we were both really big fans of burritos. (He later sold me a shirt that featured a burrito-powered bike). When I ran into him at a conference a few years ago, he told me about his old sailboat, Syzygy. The boat had been totally rusty, he said–and it had given him an idea for a book.

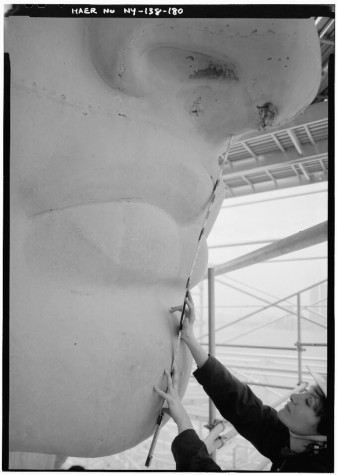

Rust: The Longest War, a chronicle of corrosion covering everything from the Statue of Liberty to the humble beer can to the adventures of a rust photographer (whose lovely image you see above), came out last month. And I’m using this as an excuse to talk with Jonny about rust, mustaches, beer and burritos. Here’s the [slightly edited and condensed] conversation we had over Google Docs:

—

Cameron: I guess I should say first that I feel dumb about rust. I remember asking my dad about it after finding a rusty ax in our yard, but I came away with the sense that rust was something that only happened to cars on the East Coast where the roads were salted, and wasn’t something that would ever affect me much. But then you just wrote a whole book about it, and it’s more than just corroded tools and the undersides of T-birds, isn’t it?

Jonny: I think that’s how we all feel about rust–just dumb enough that we allow familiarity and shame to mask the feeling. I mean, if I see it all over the place on pretty much everything, there can’t possibly be more to it, right? Because we all see it, and it’s not like there are people sounding the alarm left and right. (But, behold! There are such folks, behind the scenes!) Such is the hazard of learning to think of rust in high school as a chemical reaction. If you’re a chemist, maybe, it all worked out — but the rest of us filed away rust in our brains as something super-duper-boring, along with titration and trigonometry.

But halfway through writing the book, I realized what a crazy predicament it was: oxygen, the most abundant element on Earth, is attacking modern mankind’s most important material, everywhere, all the time. The result is not just a chemical reaction, but a phenomenon that amounts to the most destructive natural disaster in the modern world — more destructive, in fact, than all others combined.

So, sure–you may think of rusty axes and plows and rust-tastic old cars, but that’s only because you never went looking for the full scope of the matter. Metal, as I mentioned, is still our most important material (even if they say we live in the information age, we also still live in the iron age–and we use more of it per capita than ever before), and so many elements of the world we inhabit owe their existence to some defeat or prevention or control of corrosion.

When I say everything, I mean almost everything: from server rooms to spaceships to planes, ships, aluminum cans, bridges, the Statue of Liberty, millions of miles of watermains and oil pipelines, and all of the nice shiny stainless steel escalator treads and scissors that we take for granted. Even coins. But yeah, rusty old cars is what lights up most of our eyes. I’m fond of the old bumper sticker that said, “On a quiet night, you can hear a Ford rust.” That’s how most of us feel, and technically, it happens to be true (and not just with Fords).

You talk about the people sounding the rust alarm–are there particular characters/researchers that got you hooked on rust? Also, early in the book you talk about how a majority of “rust guys” have mustaches–what do you think the connection is between rust research and facial hair? (I’m also a bit confused: there are lots of photos of rust researchers in the book, but the most prominently mustachioed person I see is the author. What gives?)

Dan Dunmire, the nation’s highest-ranked rust official (he’s the director of the Pentagon’s Office of Corrosion Policy and Oversight, and his boss’s boss reports to the President), is the alarm-sounder who first hooked me on rust. I met him in Norfolk, Virginia at a Navy conference called Mega Rust. It’s funded by our tax dollars.

At the thing, I heard admirals call rust the number one enemy of the US Navy–the most powerful on Earth–and then also admit defeat. The situation was so dire that they were suggesting some pretty dramatic structural changes to the Navy- and this got my attention. But hearing Dan Dunmire talk about rust as a cultural problem really hooked me.

… And for what it’s worth, he’s got a wispy little white mustache…Trust me when I say that something like two-thirds of corrosion engineers have mustaches–and I think it has to do with a deep recognition of the difference between intently fighting a force force and responding appropriately to a force. That’s maintenance, really. Me: I’m just scruffy.

The Ball brothers (there’s a joke here, I just can’t think of it) were another group of mustachioed men who had a lot to do with stopping rust. I’ve got Ball jars, but I didn’t realize how many cans that the company these siblings started in 1882 produces. I’ll need to start looking on my beer cans for the tiny Ball signature. But actually, reading your chapter about cans made me want to stick with bottled beer. I’d always assumed can liners were to protect the food from the can. But they’re actually to prevent the can from corroding (and exploding), right?

Indeed–not only does rust make food taste bad, it makes cans seem (at least to canmakers) like time bombs. Seriously, I attended Can School, at Ball’s headquarters, and I heard cans described precisely that way: as time bombs, because rust is the number one threat to a can.

A normal consumer (who hasn’t read my book) looks at a can of Coke and doesn’t think twice; but a canmaker knows how much engineering goes into putting something as corrosive as battery acid, under 90 PSI, into a metal container no thicker than a piece of paper — and not just putting it in there, but also knowing both beverage and container will survive for a year almost anywhere you store it.

Which brings up something else I learned at Can School: that the humble, overlooked aluminum can might just be the most-engineered product on Earth. Consider the score line at the aperture — the part that goes psssshhht upon opening: it’s made with such precision that the tolerances are give or take a few millionths of an inch, which is way tighter than pretty much anything on a rocket ship. And Ball, the world’s largest canmaker, spits out 40 billion cans a year! (For what it’s worth, Ball got out of the glass business 20 years ago, and licenses the name Ball to another company — but most of us still recognize the name from glass jars even if Ball’s cans touch our lips way more often.)

Another component of that magnificent engineering is the method by which corrosion is assessed and defended against. At Ball, they deploy some pretty nifty electrochemical lab work to figure out the “pitting potential” of every new product they get, and plugging in the pitting potential to a secret formula gives them a quantitative measure of a product’s corrosivity– which in turn determines how much of a plastic lining they will need to protect cans from that product. And here’s an awesome factoid: one in seven new energy drinks that Ball tests are too corrosive to put in cans with even the maximum amount of internal coating. So Ball’s corrosion guy calls these unlucky energy-drink-makers, and says, look, you gotta change your formula. You can cut down on the dyes, or the salt, or the caffeine– anything to make it less corrosive–because right now we can’t put your overaggressive drink in our cans. Or you can start looking for glass bottles…

And then, because the whole point of a container is to not impart any odd taste on the product within, the guys at Ball (yes, many of them are mustachioed) study the interaction between the product and the coating. As such, there are something like 15,000 different internal coatings, all tailored to whatever foods or beverages they’re protecting–but the crux is that the foundation of all these coatings is BPA. It’s what makes the plastics plastic. Actually, the real crux is that I talked to a guy who has patents on these coatings–the formulas for which are held in utmost secrecy–who told me that he knows what’s in them, and what can go wrong with them, and that as such he won’t drink out of cans. He also told me he thought it’d be a good idea for the Surgeon General to modify the warning from “Women should not drink alcoholic beverages while pregnant” to “Women should not drink canned beverages.” Yikes, right? It all stems from research showing that endocrine disruptors like BPA can have effects far below the part-per-billion levels permitted by the FDA–like one to eight orders of magnitude lower.

So I don’t blame you for seeing some appeal in bottled beer. Then again, beer is really mild, so there’s much less of that internal coating in a can of beer than in a can of Coke or Mountain Dew. As they said at Can School, “cans were made for beer, and beer was made for cans.” (But don’t all writers prefer whiskey, anyway?)

I’m pretty nondiscriminatory when it comes to alcohol. Except Bloody Marys. Just the thought of one makes my stomach churn. It’s not the vodka, it’s the tomato juice–I just don’t like it, whether or not it comes in a can. But cans aren’t really what got you into this–it was your sailboat. Which you no longer own. Although it seems like a lot of good things came out of that boat, writing-wise and otherwise. Do you feel differently about rust after writing about it? And has writing Rust changed anything about your writing?

True, it was a janky old boat that got me started. Do you use the word janky? I love that word, and am guilty of using it to excess. In fact, I’m proud to show off that if you google the phrase “janky piece of shit,” my former boat is the third result that pops up. (It used to be the first.) [CW: as of 8 pm on 4/20, it has returned to first place.]

Regardless, I’m no mechanical wizard, but I certainly enjoy fixing (or at least tinkering with) things–and I’m partial to something I’ve heard repeated by some truly gifted mechanics: “if it breaks, you get to fix it.” The key is the getting part. It’s not that you have to fix something, but that you get the opportunity. After writing Rust, I think of maintenance like that. As an opportunity to take care of things–of our world.

Of course, as much as I admire engineers, there’s also only so much constant exposure/interaction one can take, so as an author I’ve also learned to discern between interests of my own and interests that make a good story. Overlap is wonderful, convenient, etc. — but it doesn’t have to be 100%. A little confusion is good. I’ve always leaned closer toward “write what you don’t know” than “write what you know.” And since I never envisioned book-length authorship, Rust has changed the way I approach potential stories. It’s given me confidence that my story-sensor is calibrated and tuned just fine, and that all I gotta do is give myself some gas (AKA burritos). That confidence is pretty useful for a writer. And to think it came from years of asking a whole bunch of questions!

—

Alyssha Eve Csuk kindly let me use her photograph at the top. The photograph of the Statue of Liberty is by Jet Lowe, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Historic American Engineering Record – HAER NY, 31-NEYO, 89—180.