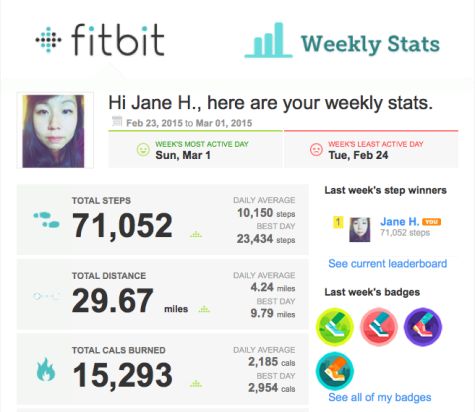

In the weeks after I bought a Fitbit, I noticed I was acting bizarre. I started carrying bags with my left arm so my right arm – the one with the Fitbit – could swing freely to ensure the Fitbit’s accelerometer would count my every step. In the evening, I would pace around my apartment until I got the gentle buzz signaling I’d reached 10,000 steps. And on days I didn’t get to 10,000, I found myself trying to justify my activity. A 30-minute bike ride doesn’t count for anything on a Fitbit, but it’s probably more or less equivalent to 1000 steps, right?

If you believe the tech industry, wearables like the Fitbit are the future. Data on your current behavior can help you better understand your habits and how to change them to meet your goals. The Fitbit, for instance, shows you raw data – steps taken, minutes active, distance travelled – so it’s easy to see progress. The device’s buzz signal is a brilliant application of psychological principles; it uses variable reinforcement, the same principle that makes playing a slot machine exciting. Because you never know exactly when you’ll get the coveted buzz, so you’re enticed to keep going. For even more motivation, you can join Fitbit’s network to “compete” with friends’ numbers.

Because self-tracking tech is fairly new, there are only a handful of studies, but early findings are encouraging. People who were assigned to use Fitbits exercised more and had lower BMIs. The sleep-tracking feature has also been a useful tool for people with sleep disorders to gather extra insight into their sleep-wake patterns.

Because self-tracking tech is fairly new, there are only a handful of studies, but early findings are encouraging. People who were assigned to use Fitbits exercised more and had lower BMIs. The sleep-tracking feature has also been a useful tool for people with sleep disorders to gather extra insight into their sleep-wake patterns.

Like those study participants, the Fitbit worked like a dream for me. I was walking so much, and my dog was getting more exercise too. I had empirical evidence that I slept more peacefully after days I exercised! But I soon found myself becoming a slave to the numbers. Rather than motivating me, the feedback from these apps was making me feel judged. When I got the flu, my Fitbit sent me an email with a red frowning face telling me I’d only walked 1000 steps. And I grew increasingly annoyed that the Fitbit registered more steps for washing the dishes than it did for biking 30 minutes or climbing a bouldering problem.

My meticulous monitoring was sucking the fun out of things. A few weeks ago, I backpacked into the Olympics to leave my digital life behind for a weekend. But halfway up the trail, my Fitbit vibrated to notify me I’d reached 10,000 steps – and that I was I still tethered to the grid, my actions tracked in real time. People always warn that turning a hobby into a job turns fun into “work” – similarly, a nice walk around the neighborhood can feel like a chore when you’re seeking that coveted Fitbit buzz or your community of friends (“friends”) competing for digital badges. It’s a classic psychology finding that getting an external reward for a goal makes people less motivated.

By quantifying success and progress in steps, calories, and minutes, we gamify our goals and risk overlooking the forest for the trees. My pacing around to hit that arbitrary 10,000 steps was a symptom of that, and it turns out I’m not the only one. In a hilarious essay, David Sedaris describes walking aimlessly around his neighborhood at night to gain the approval of his Fitbit, and others report pacing or even doing jumping jacks. It’s easy to forget that the trackers’ metrics are just proxies for the big-picture goal: improved health.

Going overboard with fitness tracking mostly results in quirky anecdotes, but taking other behavior-tracking apps to the extreme can be downright dangerous. Food tracking apps, for instance, turn your diet into a game, by tracking what you’ve eaten. Most apps have an intense focus on number of calories consumed. They represent your calorie count as a progress bar, showing you how many calories you’re “allowed” to have, and warning you when you’re closing in on your “max.”

It’s no surprise to me that these apps can be kryptonite for people who have struggled with eating disorders. I briefly tried a food-tracking app and lost 15 pounds in 3 months, but stopped when I realized how twisted my relationship with food had become. My feelings of accomplishment were tied up with the app’s arbitrary standards – 1450 calories a day – and I felt guilty every time the app displayed in bright red text that I’d failed at my goal. I found myself making questionable food decisions just to game the app: I knew an apple is healthier than a pack of mini-Oreos, but since they were both 100 calories, I’d choose the Oreos. They looked the same in my app, so I knew I could get my sweet fix without the app making me feel bad. Results from a study I read suggest that my experience is not uncommon; researchers found that dieters using a food-tracking app lost the same amount of weight as people using just pen and paper to track their eating, but not because they were eating better – app-users’ quality of diet got slightly worse, while pen and paper dieters’ diets were slightly improved.

For now, I’ve decided that I’ll be using trackers in moderation. Maybe I’ll wear my Fitbit when I’m going for a run, or use MyFitnessPal to look up nutrition information, but I don’t need an app to guilt trip me the next time I decide to skip the gym or eat a candy bar. And that may be the healthiest decision I make for myself.

Jane C. Hu is a freelance science writer based in Seattle. You can read her work at janehu.net, or follow her at @jane_c_hu.

photo by Vernon Chan

a similar confessional about strava http://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2014/jan/14/confessions-of-a-strava-cycling-addict-app