Somewhere within walking distance of me, there is a dead human body, unburied, in the woods, and it will likely never be found.

Psychiatrist Atsumi Yoshikubo arrived in Yellowknife from Uto, Japan last October 17, one of hundreds of tourists who come to see the Northern Lights every year. She checked into our nicest hotel for one week and inquired about aurora borealis tours, only to be told that the tourist season was over for the year.

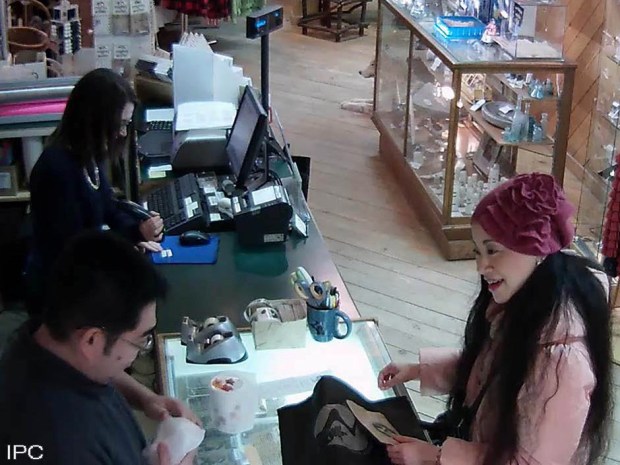

Security cameras show the 45-year-old buying souvenirs at a local gift shop – presents that remained in her luggage, presumably in anticipation of a return home, when her room was searched after she missed both checkout and flight home. She was last seen walking along the highway toward the power station.

I have never seen this city so mobilized as it was during the week after the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) released the missing persons alert. Something about a 100-pound lady in a pink coat and hat having been swallowed by the Northern landscape was enough to rouse even the most self-interested residents’ protective instincts.

Yellowknife’s population of 20,000 is contained in 100 square kilometers, outside of which is an unsettled aboriginal land claim. This has the happy effect of total wilderness within easy view of a small clump of 11-storey buildings. So it is quite possible to go on a walk from the center of town and find yourself out of your depth in a dangerously isolated situation. The temperature was in the negative teens (Celcius) – mild for the season but enough to produce hypothermia with enough exposure.

My strongest fear was foul play. About once every summer a woman is assaulted by a stranger on one of the local walking paths, and we would have been so ashamed if a visitor traveling alone had been victimized in this way.

The search-and-rescue effort started at the last point Yoshikubo had been seen and expanded when no signs were found. Local residents volunteered for the search party, but they also made it their weekend activity, taking the initiative to drive out and wander about in the area with friends, looking for clues.

As soon as you walk any distance at all in that spruce forest you realize the vanishingly slim likelihood of finding anyone at random. Less so if there has been a new snowfall to mask any prints. Even an organized grid of searchers has to be aligned in an impractically compact pattern to avoid passing over an unconscious person. Heat-sensing aerial searches failed to turn up anything either.

Then, a week later, just as suddenly as they had announced the crisis, the RCMP called off the search. Evidence had surfaced that Yoshikubo had “planned to become a missing person”. For reasons best known to herself, she had arrived here intending to disappear into the wilderness, and she had succeeded.

Many suicides in Japan occur in the Aokigahara Forest at the base of Mount Fuji. Perhaps the legendary beauty of the Northern Lights struck her as a poetic surrounding for her last view of the heavens. I found myself wishing for her sake that the weather hadn’t been so grotty and unbeautiful at her arrival. I can’t imagine it met her expectations.

As for the trinkets found in her bag, psychiatrists noted that suicides of this type are sometimes a way of testing fate: “If I am rescued, so be it; but if I am not, then it’s just meant to be.” If that was the case, then I’m very sorry we weren’t able to save her – either through a physical rescue or a psychological one.

Image: Atsumi Yoshikubo in the Gallery of the Midnight Sun