LWON is celebrating the holidays by re-running some of our favorite posts. This post originally appeared in May 2014, but sadly, the fickle inhabitants of this household have moved on to blackjack and Michigan rummy.

*

The jokers in the house are starting to learn the game of kings. The set they play with is piecemeal, with a wooden toy horse for a white knight and a lump of rainbow-colored glass for one of the pawns. The board is metal, designed for playing checkers on the road. But still the jokers learn.

Until now, chess has always seemed like a burden, something I should have learned but never really did–like shorthand, or how to fold a fitted sheet. I don’t think I enjoyed, let alone finished, the few games I played as a kid.

Yet decades later, I’ve now checked out a kids’ book about chess to find something that makes the game seem less daunting. This is it: there are games that you don’t need all the pieces to play.

In one game, The Mad Queen, a line of pawns takes on a single queen. In another, the bishop takes on all the other, stationary pieces in as few moves as possible.

In the process of playing these less-populated versions, we’ve started talking about our favorite pieces. My sons both like the king. It’s true, it’s the most valuable. And maybe I should say the queen is my favorite. After all, when they ask how she moves, I do say, “She gets to do whatever she wants!” with perhaps a little too much glee.

But my favorite–even as a young, apathetic chess player–has always been the knight. It’s got a quirky L-shaped movement; it’s the only piece that can hop over the heads of the others. (It’s also the only movement that the queen can’t imitate, although I’ve read that in some places, once upon a time, the queen could do just that.)

It’s also the only piece I know how to use better than my sons. They haven’t quite caught on to how the knight moves—at least, they haven’t yet. I found a list of descriptions of a knight’s movement that appeared in chess manuals during the last 100 years or so suggesting that even experts have trouble explaining this succinctly:

The knight moves in a peculiar way, viz., one square diagonally and then one square forwards, backwards or sideways, or vice versa, one square forwards or backwards or laterally and one square diagonally. His move combines the action of the shortest move of the bishop and the shortest move of the rook, or vice versa.’ The Complete Chess-Guide by F.J. Lee and G.H.D. Gossip (1914 edition), page 4.

Even though it’s complicated, it’s not new. The knight has moved like this since the earliest days of chess, more than a thousand years ago in India. And today, it can play games by itself, too, including a particular one that’s been of interest to mathematicians: The Knight’s Tour.

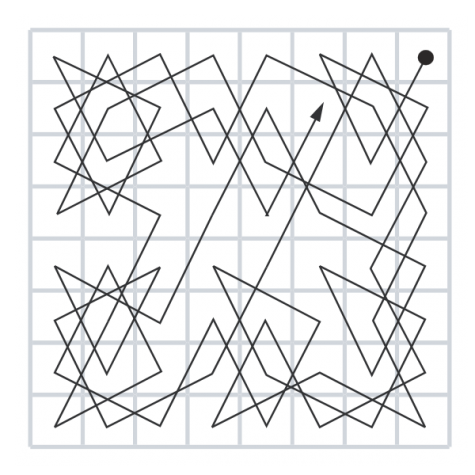

For a much more intelligent description of the knight’s tour (or anything else about chess), I will direct you to Dana Mackenzie, a science writer who also happens to be a chess champion and a former mathematician. Here’s my low-brow attempt: you try to move the knight so that it hits each square once, and only once.

Mathematicians and computer scientists are interested in how many possible variations of the knight’s tour exist, particularly tours where the knight can return to its original square at the end, called a closed tour. Some researchers have found 13,267,364,410,532 ways to do it—and a recent study, using an algorithm that simulates the movements of a group of ants laying pheromone trails, found nearly half a million more solutions.

People had also been trying to find ways that a knight’s tour can also be a magic square—where all the squares on horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines add up to the same number. (Check out this video.) It turns out that you can have a semi-magical square, but not one in which the diagonals also fall into line.

We all have a long way to go before we figure out how to make the knight gallop around the board. But now we’ve started to try it out around the house, too. We have a battered 60-year old parquet floor that we’ve had a love-hate relationship with—until this weekend, when its checkerboard pattern took on new meaning. Last night we played a game of the Mad Queen, in which swiftly, stealthily, each pawn was soon eliminated.

This time, the queen did not vanquish her challengers with a giant sword. Instead, she squeezed the pawns and spun them around until they giggled. And then she ordered them to bed. After all, the queen can do whatever she wants.

**

Images

Los Tres Caballos and Knight’s Tour, Wikimedia.

I think of the knight’s move as a metaphor for things that behave unexpectedly, like for instance, candied orange peels. That’s a real knight’s-move recipe. You’re proceeding in an orderly manner directly ahead and whack! it hits you from the left. Thank you for re-posting this.

How could I forget candied orange peels? Will you direct me to the recipe again?

Happy to be of service: https://www.lastwordonnothing.com/2014/05/15/the-iniquity-of-candied-orange-peel/