While Murph was still at Princeton, in his first years there, he was spending summers consulting, sometimes for defense contractors, sometimes for the Los Alamos National Laboratory. (A lot of physicists did this: academic scientists’ salaries run for nine months; they needed summer money.) Then a little later, during the post-Sputnik years, Murph gave the government advice on science matters (radar, nuclear bombs, and missiles are just physics) as a member of an unusually-powerful President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). So between defense consulting and PSAC, not to mention the Manhattan Project, Murph developed a sense that he and other scientists should take over from the first generation of science advisors — whom he respected but didn’t much like and who were usually from MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass. So he thought he should, as he said, “step up to the plate.”

So one summer he participated first in a sort of briefing on science-related defense problems called Project 137; and then the next summer, he and two other physicists formed a group of contractor/advisers who were independent, who were full-time physicists advising for summer money only, whose salaries didn’t depend on their advice. Nothing like this group had been done before and really, nothing has since.

Mildred named the group, Jason. Murph was its first head; he stayed active in the group until around 1967. By this time, Jason was being asked how to stop North Vietnamese infiltration into South Vietnam. Jasons, Murph included, came up with a plan by which the enemy would set off hidden sensors whose signals were to be detected by our airplanes which would bomb the infiltration routes. The Jasons called it the Air-Suppported Anti-Infiltration Barrier. When the military took over the plan and used it to bomb the enemy everywhere, the newspaper called it (wrongly) MacNamara’s Wall. The Senate hearing on its use, years later, called it the electronic battlefield and said “it has the possibility of being one of the greatest steps forward in warfare since gunpowder.” Which it did: it’s the way wars are fought now. But it’s not what the Jasons intended. And when the Pentagon Papers published the Jason report, Jason’s was confused with reports by the older Cambridge physicists, and caught high-temperature hell from the activists. For some Jasons, Murph in particular, the episode could have come straight out of Faust.

Here’s Murph talking again, starting at the beginning:

§

Project 137, the briefings were very intense. And they went sort of from morning to night, and it was hotter than hell in Washington in the summer, as it always is. I remember some of them being dreadfully dull and some of them being quite interesting. I can’t remember in detail, but there was one involving biological warfare, which involved infecting rats with some terrible disease and driving them against an enemy. It made everyone sort of sick to the stomach. I remember one of the briefers was a man named Herman Kahn. He worked from Rand, he was a big nuclear war, I wouldn’t say “enthusiast,” but he was. He could talk for four hours on almost any subject, and in these briefings he did.

§

You have to put yourself back into the spirit of those times, of Cold War, concern about the level of scientific expertise in the military which was not at all great at that time, and a feeling of patriotism and a feeling of obligation that we couldn’t continue to rely on these older people. And that we had to take some responsibility. There’s a kind of glamour, of course, of knowing secrets. I had a security clearance – I had had a security clearance since I was 22 years old – and continuously had been cleared throughout my life.

§

In 1966, Jason met in Santa Barbara. And I had decided that it might be useful for Jason to take a look at aspects of the war in Vietnam and see whether we could make any contribution. Now quite independently of me, the pundits in Cambridge came to a similar, unrelated conclusion. That gang – you know, there was a common misperception that the real seat of government was in Washington but it was in fact in Cambridge. Anyway, the Jasons were in Santa Barbara, five or six people, who worked pretty hard on aspects related to the electronic barrier, having to do with sensors and communication.

§

I think people do worry about the consequences of the things that they work on. When we worked on this MacNamara Line in Vietnam, our objective was not to kill the North Vietnamese but to lower the temperature of the war so it could be solved by political means. So we were at least able to convince ourselves that we were not nasty people. The fact that on the MacNamara line, certain people did in fact get killed in order to discourage them from coming down [the Ho Chi Minh trail], well, that’s the price you gotta pay.

§

[The Jasons planned the electronic barrier, but the Air Force carried it out] That was another one of these revelations of the military for me. They were very skeptical about the barrier, initially. And they were finally ordered to do it, to implement it. And whereas we had gone into this with the notion of slowing the infiltration, that’s not the way they looked at it at all. We looked at it as a replacement of the bombing in the North, which we knew wasn’t worth a damn. But they looked on us as an add-on, they would bomb the North and they would do this. And that’s the military philosophy: any small advantage, no matter if it’s one percent or two percent, their point of view is to do it.

§

The contact with the Department of Defense was through this Cambridge gang. And it was almost a textbook demonstration of the arrogance of physicists. After all, we had won World War II, a much bigger operation. To mop up this little thing was clearly something we could do and everybody else was fucking it up, so it was time to take it over. And it was the greatest mistake that any of us ever made. What we should have told McNamara at the time was to take a flying jump, we don’t want to have any part of this. We subsequently took a tremendous amount of heat, Jason did — undeservedly in the sense that the center of gravity of the operation was in Cambridge but deservedly to the extent that we agreed to have something to do with it.

§

I’m going to quote myself. I once gave a talk to the American Physical Society and the first sentence was, “It’s part of the folklore of physics that physicists not only can do anything but they can do it better than anyone else.” So the idea is, that there are hard problems here, that we’re physicists, we’re so goddam smart, we will solve those problem for you poor bastards. So there’s an element to that, there really is an element of that. That you can take something you really don’t know anything about and make a contribution. And since it’s a bunch of extremely smart guys, they ordinarily can. That’s part of the attraction, to show these drones that the thing they labor over all the time can be dispatch with a few clips and swaths of a sword by a brilliant theoretical physicist.

§

Following the publication of the Pentagon Papers, we were just harassed terribly. It was unpleasant, it was extremely unpleasant. [Part of the reaction] to being so harassed was a feeling of shame, that we’d gotten into it at all.

§

I remember the first time I met Daniel Ellsberg – it was in connection actually with a Jason study, I don’t know what the study was and I better not talk about it – in the Pentagon, and he had just come back from Vietnam. And he said, “You are being fed a continual line of bullshit. Everything they say about these body counts and winning the hearts and minds of the people is just sheer baloney.”

§

I had just come back from a briefing – I was on the President’s Science Advisory Committee at the time – and Walt Rostow, who was the National Security Advisor, came and fed us some absolute bullshit about what was going on in Cambodia and Laos. And we knew that it was a lie. And I was just furious about it. By that time, giant brain had kicked in and I’d become extremely disillusioned about the whole Vietnam operation.

§

I’m ashamed of how long it took me to recognize this. I had a lot of friends in the academic world who kept telling me this, and there is this terrible arrogance of power that you have. If you know inside information, you think everyone who is on the outside doesn’t know what they’re talking about. And the sad fact of it was, they knew what they were talking about and I didn’t. And I’ve always been ashamed at how slow I was in making that realization.

§

I was a supporter of the nuclear freeze movement. Not in a clandestine way. I often encountered groups would say, “why don’t you goddam scientists just stop doing these things?” And I pointed out to them that scientists as a group are just as patriotic as the next person. And if our government says, in our judgement we have a national need to build ballistic missiles or bombs, whatever it is, as patriotic citizens, as a group, we have an obligation to help what the public has decided is our national need. Every individual can act on their own conscience as to whether they want to participate in that or not. But to expect the scientists to withhold their favors, like the women of Lysistrata, is unreasonable. And it’s unfair to put the blame on the scientists for doing something that you have said has to happen.

§

I was asked to write a scientific autobiography by the Sloan Foundation. And I was supposed to provide for them 4 or 5 chapters and they would look at it and decide [whether to publish it]. It took me 3 or 4 years to write those first 4 or 5 chapters, during which time two things happened. One was that the Sloan Foundation decided it would discontinue this series. And they also changed the publisher of the volumes that had come out in the past. And the new publisher said he was tired of publishing books that sold 1500 copies to libraries and that’s all. I was to some considerable extent relieved. Because I’d felt all along that what I’d write might be interesting to some subset of my friends. I have had an interesting life. But the kind of audience it is interesting to, I think is relatively small. I just lost my enthusiasm for it. Maybe someday I’ll finish it.

_____________

I think Murph never wrote more than those 4 or 5 chapters.

The arguments Murph is making are moral. Physicists have no better handle on moral arguments than the rest of us, but they can be in the position of having to make decisions based on them. That is, unlike the rest of us, they’re sometimes asked to help figure out the next gadget to either kill people or ensure our national security, both are the case. I have no talents of use to national security, so any moral arguments I made, or judgments I make of other peoples’ moral arguments, are airy theory.

And as everyone is probably tired of hearing, I wrote a book about Jason.

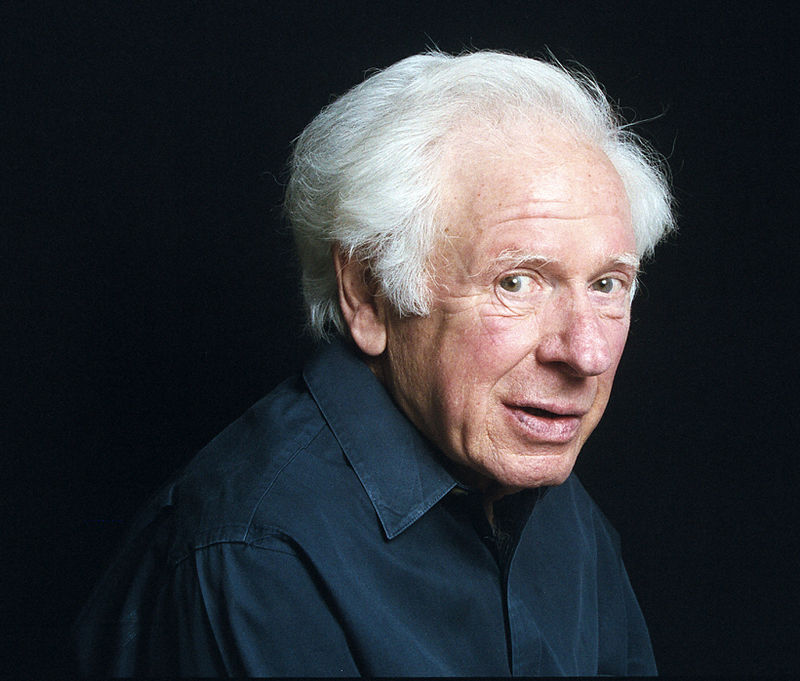

Gorgeous photo of Murph by Manny Rotenberg, and used with his kind permission

One thought on “Marvin Goldberger, Always Called “Murph”: Part 2”

Comments are closed.