I spent about seven hours in the operating room at Johns Hopkins Hospital being worked on by a highly skilled surgical team, followed by a day in intensive care and five days in regular care. I also had a battery of pre-op and post-op tests and consultations to investigate the aortic aneurysm that put me on the operating table. When I asked friends to guess how much all that cost, not one estimated less than $100,000. I probably will never know who came the closest.

I spent about seven hours in the operating room at Johns Hopkins Hospital being worked on by a highly skilled surgical team, followed by a day in intensive care and five days in regular care. I also had a battery of pre-op and post-op tests and consultations to investigate the aortic aneurysm that put me on the operating table. When I asked friends to guess how much all that cost, not one estimated less than $100,000. I probably will never know who came the closest.

I know exactly how much Johns Hopkins and some two dozen surgeons, anesthesiologists, radiologists, cardiologists, and assorted other specialists billed Medicare, the government-sponsored program that provides most of my health coverage: just under $64,000. And I know how much Medicare paid. But those sums aren’t the actual costs of the care I received. Nor do they reflect how much an uninsured patient or a private insurance company would have been billed, though it almost certainly would have been much more than $64,000. Welcome to the bizarre and confusing world of American medical price setting, in which health care providers strive at least to balance their overall costs and payments–and in most cases make a profit–and in which charges vary according to who’s paying.

Because I’m one of about 50 million Americans covered by Medicare, and because I also opted to take out supplemental insurance, which covers costs that Medicare doesn’t pick up, I haven’t received any medical bills. (The only bill I have received directly is $60 for TV feed to my hospital room.) It’s almost like being back in the United Kingdom, where I lived until I was 25 and where people don’t have to worry about being able to afford the next medical bill–or fight with insurance companies about how much they will pay.

Because I’m one of about 50 million Americans covered by Medicare, and because I also opted to take out supplemental insurance, which covers costs that Medicare doesn’t pick up, I haven’t received any medical bills. (The only bill I have received directly is $60 for TV feed to my hospital room.) It’s almost like being back in the United Kingdom, where I lived until I was 25 and where people don’t have to worry about being able to afford the next medical bill–or fight with insurance companies about how much they will pay.

All the bills for my treatment went first to Medicare and then to my supplemental insurance company. That made it easy to get a breakdown of the amounts the hospital and doctors claimed from Medicare: I simply downloaded a record of all Medicare claims and payments from MyMedicare.gov. There were no big surprises, such as huge charges for brief physician consultations that Elizabeth Rosenthal wrote about recently in an excellent article in the New York Times.

The Medicare records indicate that Johns Hopkins billed Medicare just over $32,000 for inpatient hospital costs: “room and board,” operating room services, intensive care, drugs, surgical supplies, etc. Another $7000 was billed by Hopkins and a hospital in my home town for outpatient lab work and diagnostic CT and MRI scans. Physicians’ charges for the surgery itself, anesthesiology, clinical management of my hospital care, and sundry specialist services came to just over $25,000.

The way the system works is that Medicare approves a sum for each hospital claim based on fixed amounts for specific services, such as an appendectomy, and it approves physicians’ charges according to a preset fee schedule. In my case, the hospitals billed Medicare the fixed amounts for the services they provided, so Medicare approved the entire $39,000 they claimed. But Medicare approved less than half the total amount claimed by physicians.

Medicare reimburses hospitals the total fixed amounts for in-patient hospital services minus a $1216 deductible, and 80% of the amounts it approves for physicians’ fees and most outpatient procedures, with a yearly deductible of $147. The patient is responsible for the deductibles and 20% of the Medicare-approved fees. For me, that would add up to about $5000. I’m glad I took out supplemental insurance.

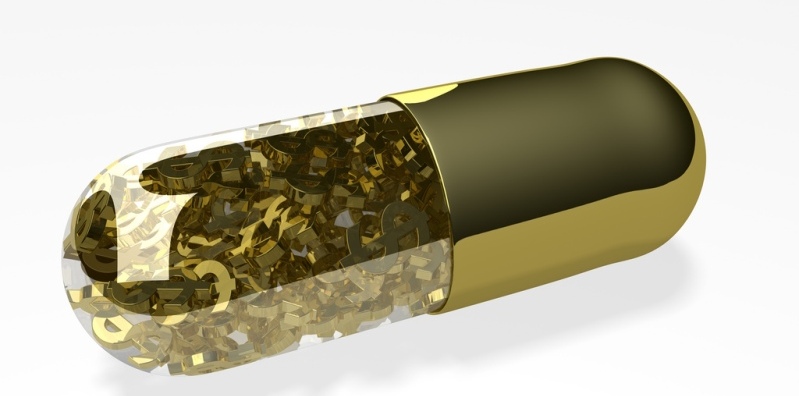

For Americans who lack medical insurance and who don’t qualify for Medicare or Medicaid—the government-sponsored program that covers people with limited incomes and no further assets—the consequences of treating a medical condition like mine would be catastrophic. Not only would the patient be liable for the entire charges but the bill for the treatment I received would likely be much higher than $64,000. The reason: Hospitals wouldn’t be constrained to charge the amounts Medicare pays, which are generally lower than the actual costs. If the difference between the physician’s claims for my treatment and the amounts Medicare approved is any guide, the total bill could easily exceed $100,000—just as my friends guessed.

It’s easy to see why Medicare has become a hugely popular program, at least for those over 65. That popularity was evident in 2012 when House Republicans unveiled a budget proposal crafted by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc) that would turn Medicare into a voucher program. Democrats pounced and made it a campaign issue in the presidential election that year, in which Ryan ran as the Republican candidate for Vice President. We know how that turned out. Of course, other issues played a big role, but it’s best not to antagonize millions of seniors—who, unlike the majority of eligible voters in the United States, actually tend to vote.

It’s easy to see why Medicare has become a hugely popular program, at least for those over 65. That popularity was evident in 2012 when House Republicans unveiled a budget proposal crafted by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc) that would turn Medicare into a voucher program. Democrats pounced and made it a campaign issue in the presidential election that year, in which Ryan ran as the Republican candidate for Vice President. We know how that turned out. Of course, other issues played a big role, but it’s best not to antagonize millions of seniors—who, unlike the majority of eligible voters in the United States, actually tend to vote.

It wasn’t always that way. Although the bill that created Medicare passed in 1965 with a healthy bipartisan majority, the idea of a government-sponsored health care program was highly controversial. Opposition lessened over the years, though, as more and more people enjoyed the benefits. The same could happen with the Affordable Care Act (why did even Democrats get suckered into calling it Obamacare?)—if the Republican Congress doesn’t cripple it by picking away at its core provisions, if the Supreme Court doesn’t nix subsidies in many states, and if enough people sign up for coverage under the Act. Yes, that’s a lot of ifs.

In my case, I think it was money well spent on first-class care. But that’s easy to say, since most of it wasn’t my money (though Medicare taxes I paid over more than 40 years plus interest probably covered the costs). But the $60 for TV in the hospital wasn’t as well spent: I only watched it once, to see the Washington Nationals get beaten by the New York Mets. But $60 is about the price of a ticket to the game plus a beer and a hotdog–and I did watch it in the high-priced comfort of my hospital room.

§

This is the seventh and last in a series.

__________

Colin Norman has been a science journalist for more than 40 years. He is the former news editor for Science magazine and currently lives in Lewes, Delaware.

______

Photos: Bill Brooks, via Flickr; Evlakhov Valeriy, via Shutterstock; Djembayz, via Wikimedia

Just a couple of years ago I had a mild heart attack (splints in and out in one day) and just a couple of years away from retirement and Medicare I appreciate this series. Thanks for sharing.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals are the only company with legal rights to sell Xyrem (natriumoxybate/GHB).

A substance made for some $10 pr. gallon. Because they know that the insurance companies will pay, they charge $5000 (yes five thousand dollars) for a bottle of 180ml. Pharmaceutical cynicism at it’s best.