This story has a happy ending. I promise.

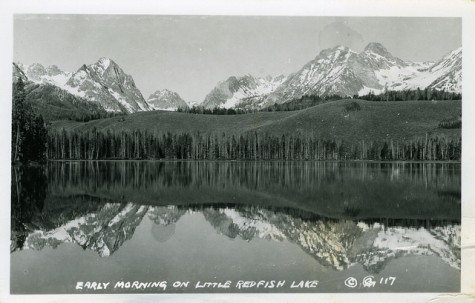

Every year before the turn of the last century, some 150,000 sockeye salmon made an epic journey: They traveled from the Pacific Ocean up the Columbia River, hung a right into the Snake, a left into the Salmon, and finally, after swimming upstream for 900 miles, arrived in the clear, icy waters of central Idaho’s Redfish Lake. In late summer and early fall, the lake was so thick with sockeye that white settlers named it after the fishes’ scales, which turn from silvery-blue to brilliant red in breeding season. But in 1913, a new dam on the Salmon blocked fish access to Redfish Lake. After the Sunbeam Dam was blown up in 1934, the sockeye began to return, but their numbers were still recovering in 1962, when the first large federal dam went up across their migratory route in the Snake River. Eventually, four large dams were built across their route in the Snake, and another four across the Columbia.

The tens of thousands of sockeye that had struggled upstream to Redfish Lake each year became a few thousand, and then to few hundred, and then a few dozen. In 1991, there were four. In 1992, there was one.

His name was Lonesome Larry, and while his life was unlucky, his death was quite another matter.

In 1990, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes—whose members have caught, eaten, and revered sockeye for generations— petitioned the National Marine Fisheries Service to list the Snake River sockeye population under the Endangered Species Act. The Snake River fish travel further and to a higher elevation than any other sockeye in the world; they’re also the southernmost population of the species. And it was extremely obvious that they were about to disappear forever. So for once, the wheels of government turned swiftly, and by the time Lonesome Larry showed up at Redfish Lake in 1992, Snake River sockeye were listed as endangered.

Biologists knew that the sockeye couldn’t be saved without serious human intervention. The previous year, they had caught the three male and one female sockeye that returned to Redfish Lake and used their sperm and eggs to found a Snake River sockeye hatchery program. Larry (the origin of his name is apparently lost to history) was also sacrificed for his species’ cause: He was caught and injected with hormones so that he produced an alarming amount of sperm, which was then collected and frozen. Over time, biologists collected sperm and eggs from other Snake River sockeye to enlarge the gene pool.

For the next few years, though, the sperm stayed in its freezer: no female sockeye appeared in Redfish Lake. Finally, in 1996, a few females returned, and Larry’s legacy went to work. Each year, eggs were fertilized with sperm from Larry and other Snake River sockeye in a hatchery, and the hundreds of thousands of young fish that resulted were released into the lake. “We froze him and thawed him and froze him and thawed him,” remembers Paul Kline, assistant chief of fisheries for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Still, the waiting wasn’t over. During the 1990s, despite the hatchery work and fish-passage improvements downstream, a total of 16 adult fish returned to Redfish Lake to breed.

Larry’s luck turned in 1999, when the first hatchery-born fish began to return to the lake. (Biologists now believe that the recovery was helped along by a few non-migratory sockeye that managed to overwinter in Idaho.) In 2008, 650 adult fish returned, and in 2009 there were 833. As of this week, almost 1,500 sockeye have returned to Redfish Lake, more than in any single year since 1955. About 1,000 of those fish were released from hatcheries, but the rest were born in the wild; genetically, all are Snake River sockeye. Managers hope that over time, the proportion of naturally-spawned sockeye in Redfish Lake will grow, and the need for hatchery fish will shrink. Lonesome Larry’s genetic legacy, however, will persist.

I promised you a happy ending, but the prospects for salmon, in general, are shaky. Climate change is causing multiple problems, especially for southern populations, and dams have been devastating salmon habitat for decades; on the Columbia, some young sockeye must be barged around dams as they move downstream. Full recovery for the Snake River sockeye is still a long way away, and hatcheries are an expensive, imperfect way to get there. Still, the story of Redfish Lake is one of several bright spots for salmon in the Pacific Northwest this year, and all are due to people, however belatedly, doing the right thing for some very cool—not to mention ecologically important—fish. These stories may not be good enough, but they are genuinely encouraging.

Lonesome Larry—the corporeal Larry, that is—was preserved and is now mounted on the wall of the Morrison Knudsen Nature Center in Boise. In 2012, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Larry’s heroic solo return to Redfish Lake, Idaho Rivers United took him on a tour of the state. Today, if you look closely at his hooked jaw, you might be able to discern a smile.

Top photo of sockeye salmon eggs courtesy of NOAA Fisheries-West Coast Region.

Postcard of Little Redfish Lake in the 1950s courtesy of WaterArchives.org.

One thought on “The Legacy of Lonesome Larry”

Comments are closed.