There a few moments in your childhood that stick with you the rest of your life. I don’t mean first kiss, prom, or that time you punched Kelly Weir in the stomach for stealing your bike (believe me, he had it coming). Those are big moments. I mean the little things – the things that everyone else has forgotten but you.

There a few moments in your childhood that stick with you the rest of your life. I don’t mean first kiss, prom, or that time you punched Kelly Weir in the stomach for stealing your bike (believe me, he had it coming). Those are big moments. I mean the little things – the things that everyone else has forgotten but you.

For me, one such moment was during my first week of seventh grade. It was gym class and Mr. Morris wanted me to do something. I don’t remember what it was, that’s not the crucial bit. I just remember it was on the grass, near the softball field that no one ever used. Morris, who had the sort of chiseled, aged face that you could imagine drove all the girls nuts in 1962, snapped his fingers and said, “Focus!”

Then he said something I’ll never forget. “Focus on what you are doing, Erik. You’ve heard that before, haven’t you?”

Indeed, I had heard it before. I heard it every year, in fact, in elementary school. Mrs. Ward, Mrs. Kraft, Mr. Manegetti, they all probably said it. What – I was kind of a space cadet, okay? I daydreamed. I had my own world that was way more interesting than cloud charts and “To Kill A Mockingbird.” So sue me. My grades were good and I didn’t cause trouble.

But this shocked me. I had a reputation. Teachers were actually warning each other about me – prepping next year’s gym coach for the terror that was Erik Vance. Was I really that bad? Sure, I’d make up stories in my head and stare at ants, who doesn’t? Sure, maybe an elementary school teacher would warn another about me in the coffee lounge during recess. What else were they supposed to talk about?

But my reputation was so bad it actually leapt from elementary school to middle school. Back in 1988 Ritalin wasn’t really a thing (it goes back to the 60s but only took off in the 90s) – I only knew one kid taking it and we all thought it was because he was broken somehow. Besides, being raised in a Christian Science family it was hard enough to get aspirin, let alone a powerful psychostimulant.

But after that day in the 7th grade, I had a perverse sense that there was something wrong with me. Now, a lot has been written about kids who can’t pay attention, and I’m not going to wade into a pool that deep without my floaties.

But I might nibble around the edges.  You see, currently there’s a debate in child development circles raging over when and if touch screens are good for kids. One of the many participants is a guy named Dimitri Christakis who I have written about before and who’s taken some heat for partially endorsing iPads for young kids.

You see, currently there’s a debate in child development circles raging over when and if touch screens are good for kids. One of the many participants is a guy named Dimitri Christakis who I have written about before and who’s taken some heat for partially endorsing iPads for young kids.

Christakis is probably my favorite developmental psychologist (yes, such a thing can exist) because of an amazing study he did in 2012. Essentially, he overstimulated a bunch of mice for 42 days with frenetic noises and light. Afterwards, they seemed to have the mouse version of attention deficit disorder.

When I spoke to him a couple years ago, he laid out a convincing case for the dangers of extended TV watching. For instance, he said in 1980, kids started watching TV at four. Today they start at four months and by preschool they watch 4.5 hours of TV in the 12 or so hours they’re awake. “That’s about 30 percent of their waking hours in front of a screen. It’s hard to imagine that that doesn’t have some effect on brain development,” he said.

The key, though, is the kind of TV they watch. This is where Christakis is different from most researchers, he doesn’t lump all TV together. He often starts his talks with a clip from Mr. Rogers. The iconic friendly neighbor slowly sits down at a restaurant table and slowly lays out a napkin to put on his lap – narrating every action as he does. For an adult, it’s a bizarrely drawn-out process. Next he shows a clip of the Powerpuff Girls – a dizzying barrage of images of explosions alongside an angry monkey who seemed to be there totally at random.

He says there’s a difference between fast, violent TV (which he equates to the light and noises inflicted on the mice) and educational TV (for instance, “healthy” shows ask a question and then wait a moment for the viewer to answer). Sesame Street might be healthy while Baby Einstein – with its crazy bubblegum pace, is not. Christakis theorizes that really young kids who watch TV at the wrong pace are setting their brains up for a different pace than real life – hence, ADD.

I have no idea how this theory will shake out, but it’s a fascinating notion. A sort of internal ticking that shows toddlers when to expect what. There’s no question that TV has gotten faster. Just for the hell of it the other day I watched an episode of 80s-era Transformers, which I remember as being violent, crazy, and super fun. I expected the terrible dialogue and cheesy graphics but I was shocked to see just how slow it was. I mean, dude, Optimus, stop sermonizing and shoot the bad guys.

As I read reports like this one that try to apply what we know about TV watching to the more dynamic world of tablets and online gaming, I see scientists like Christakis struggling to draw lines across what is healthy and what is not. What’s the Mister Rogers of the iPad?

These days I’m contemplating having my own children and imagining the genetic, pharmacological, and high-speed entertainment influences on their world. I wonder if they will be better or worse off than I was.

In high school, I found activities that honed my mind and forced me to pay attention – music, theater, rock climbing. I remember that after a weekend of climbing – where fear and adrenaline tend to keep you on target – I’d come to school on Monday and be able to retain more than on the previous Friday.

Yet to this day, I have trouble concentrating (wow, cicadas are kind of crazy, right?). It doesn’t help that I’ve chosen the very worst field for people whose minds wander (oh look, “True Blood” is in its last season!). All day I sit at home and try to look at a computer screen that, frankly, hates me (whoa, Palestine is insane right now – any decent person would take a hour and read about the crisis).

But every time my mind wanders, I see Coach Morris’s craggy and weathered face and feel a pang of embarrassment. Then I repeat a simple mantra that I have held from that day until this.

“Focus, Erik. Focus.”

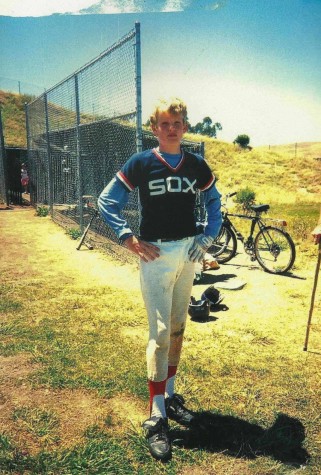

Photo Credit: Shutterstock and the Vance family album.

Thank you. That is all.

Thank you for this article Erik. I had a space-cadet reputation as a child as well. We were not necessarily aware of our “mental drifts”, until someone from the outside told us. In your case, it was Coach Morris. But growing older, this new-found awareness enables us choose when we want to focus on the present moment and when we simply want to shut it out (like when we are fed information we do not consider accurate for example, or when we are bored) . I think that’s a great mental advantage and it yields great mental flexibility. Our imagination is vivid and we are learning how to use it. I don’t think it’s a “bad” thing nor should it necessarily be perceived as a disability (i.e. ADD) in all cases. As for the TV issue, I think you are either a “space-cadet” or you are not and the impact of technological changes on mental development will vary from child to child.