Splendid, isn’t it. It’s UGC 8335 — one name, so once it was apparently mistaken for one thing though obviously it’s two. They’re spiral galaxies in the process of running into and through each other. This is a photograph by the Hubble Space Telescope; the galaxies are really there; this is real. You could think of this photo as a single frame in an extremely long movie. But you could see the movie only if somebody made it up out of whole cloth, i.e., not real. Like this:

Splendid, isn’t it. It’s UGC 8335 — one name, so once it was apparently mistaken for one thing though obviously it’s two. They’re spiral galaxies in the process of running into and through each other. This is a photograph by the Hubble Space Telescope; the galaxies are really there; this is real. You could think of this photo as a single frame in an extremely long movie. But you could see the movie only if somebody made it up out of whole cloth, i.e., not real. Like this:

The movie isn’t made up entirely: it’s an animation, a computer simulation built out of the behavior of stars and gas, and the laws of gravity. Galaxies really do fly through space, and if they get close enough to feel each other’s gravity, they interact. They do this dance, their stars and gas tracing out the laws of Newtonian and Keplerian physics. All this physics goes into the computer and out comes the simulation.

Simulations are rigged to match observed reality, but they can be rigged only so far. A good match between simulation and observation means astronomers have figured out the physics correctly and can generally believe their idea of what’s going on. This is an example, a running simulation interrupted by real photographs of real collisions.

Over the last 8 or 9 billion years (in a universe nearly 14 billion years old), up to a quarter of the galaxies have probably collided. In the simulations and in reality, nothing truly collides in the way we think of collisions: hit head on, smashed into pieces. The scales here — the size of the stars, their distances apart — are such that the galaxies pass through each other at first. They slingshot past each other, fall back together, wheel back out, fall back in. Their stars are pulled out of orbit, and they change shapes over and over until two galaxies merge into one and the grand spirals settle into the calm equilibrium of an enormous elliptical. Like this:

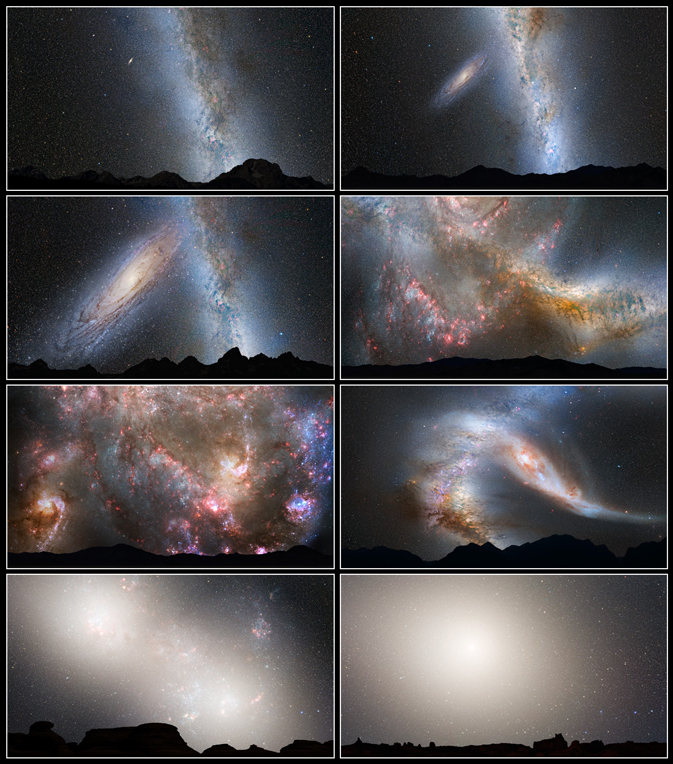

These pictures are a variant of reality, an illustration based not only on physics but also on HST photos. This is us, the Milky Way, and our neighbor spiral, Andromeda; we’re headed straight for each other and it’s a matter of time until we collide. The collision will play out over the next seven billion years in the night sky and when it ends, we’ll be just one galaxy.

These pictures are a variant of reality, an illustration based not only on physics but also on HST photos. This is us, the Milky Way, and our neighbor spiral, Andromeda; we’re headed straight for each other and it’s a matter of time until we collide. The collision will play out over the next seven billion years in the night sky and when it ends, we’ll be just one galaxy.

This is such pleasure — the real splendor, of course; the time scales that you can only simulate, that you’d have to be God to see; and the galactic dances straight out of Romeo and Juliet, spinning away and returning, union and reunion.

_____

The link for Romeo and Juliet takes you to a ballet video. The first bit is romantic hoo-ha; start around 4.00 if you don’t believe that two people, apparently all muscle and no bone, look like colliding, merging galaxies.

Photo credits: UGC 8335 – NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage (STScI/AURA)-ESA/Hubble Collaboration, and A. Evans (University of Virginia, Charlottesville/NRAO/Stony Brook University); simulation of collision of spiral galaxies – NCSA/NASA/B. Robertson (Caltech) and L. Hernquist (Harvard Univ.); comparison of observed and simulated collisions – Visualization by Frank Summers (Space Telescope Science Institute). Simulation by Chris Mihos (Case Western Reserve University) and Lars Hernquist (Harvard University); collision between the Milky Way & Andromeda – NASA; ESA; Z. Levay and R. van der Marel, STScI; T. Hallas, and A. Mellinger

They really do look like a ballet. Loved this.

I think the reason there are so many galaxy collisions but not star ones is because in proportion to their sizes, the distance between stars is much greater than between galaxies…I think.