We haven’t had a Triple Crown winner in 36 years, since a horse named Affirmed won in 1978. This year, there’s a lot of buzz around a chestnut colt named California Chrome. He’s already won the Kentucky Derby and The Preakness, and word is he has a good chance to win Saturday’s mile-and-one-half Belmont Stakes, one of 12 horses slated to run.

I know that the horses are gorgeous; I’ve loved horses all of my life. The pageantry of thoroughbred racing at this level is hard to resist, and California Chrome is already getting rock star treatment, with video of his arrival at Belmont Park in New York, journalists in tow. The gleaming horses, the racing silks, the landscaped racetracks varnish over a sport with an ugly underbelly that’s been lost in the pre-race excitement.

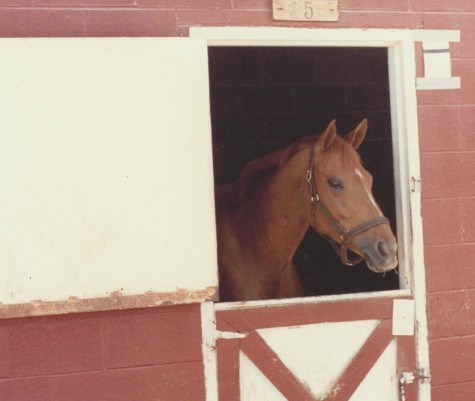

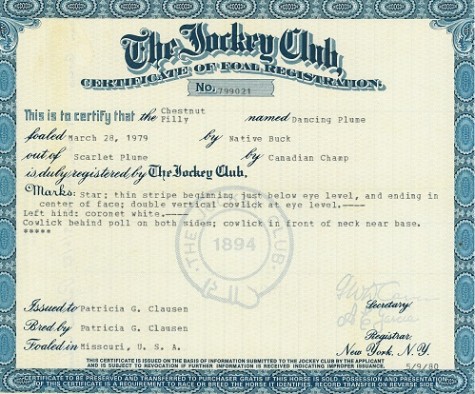

I bought my first horse, named Hank, not long after college, when I finally had an income. I wanted to learn to jump and eventually go to horse shows (which are another abusive environment because owners and trainers of show horses can be just as abusive as the owners and trainers of racehorses). At the time, I couldn’t afford anything fancy, but Hank and I did well together. My second horse was a chestnut thoroughbred mare that I bought “off the track,” an expression for horses that don’t succeed in a racing career. Her registered name was Dancing Plume (she was nicknamed Natalie) and she had good bloodlines: She was the great granddaughter of Native Dancer, perhaps not a household name outside of horse racing but a talented horse who only lost one race, the Kentucky Derby in 1953. He was also a prolific sire whose offspring were top racehorses.

Natalie hadn’t lasted long at the track. She was fast but lazy. She also learned to ever-so-subtly drop her left shoulder, ridding herself of riders without much effort on her part, so she probably wasn’t the most popular girl in the training barn.

During my 17 years with Natalie I learned to love thoroughbreds for their elegance and spirit. But I learned to hate horse racing. Racing isn’t kind to horses. Thoroughbreds are raced as two-, three-, and four- year olds because they’re not fully muscled yet, which makes them lighter and faster. Even training is hard on their legs. Thoroughbred racehorses can also suffer injuries serious enough to require euthanasia, just from a flat out gallop.

I’d pretty much had it with racing by the time the great Barbaro broke a leg during the Preakness Stakes in 2006. In 2008, a filly named Eight Belles collapsed right after the Kentucky Derby, and was euthanized at the track. By then, my horse friends, which include my in-laws, knew I would no longer turn on any of the Triple Crown races.

Horses like Barbaro, Eight Belles, and Ruffian, a filly who broke down in a “girl versus boy” match race at Belmont Park in 1975 against a horse named Foolish Pleasure, had such public deaths. So many others happen on small tracks, in less heralded races, during training, during racing season.

Lately, fortunately, I have noticed more attention brought to the darker side of thoroughbred racing. I’d always wondered why animal rights groups went after the research use of animals but seemed to give racing a pass. That changed recently when PETA went undercover to expose abuse by prominent trainers. I can’t say that I’m a huge fan of the organization but the resultant story by Joe Drape ran in The New York Times on March 19, 2014. Drape’s story links to another series The Times ran in 2012 stories on the dark side of thoroughbred racing.

After the PETA story, Andrew Cohen of The Atlantic posted a commentary on the PETA video and he Times story that’s far more eloquent than I could ever muster. In it he writes:

“You can be cruel to a horse by hitting it or “buzzing” it with an illegal device. You can abuse a horse by forcing it to race lamely when it is lame. And you can abuse a horse by giving it too many drugs to get it to the races (or to make it race faster). So if racing officials won’t stop this practice for the sake of bettors or owners, how about stopping it for the sake of horses?”

Honestly, horses can find any number of ways to hurt themselves without this kind of abuse. Natalie tore up an ankle once without leaving her stall. She hurt a different ankle in a turnout pen. But intentionally harming creatures under our care because racing is big business is unforgivable.

With all of the Belmont buzz surrounding California Chrome, it seems wrong to look the other way.

Some former racehorses do end up with the kind of lives that Natalie had. I showed her for a few years and then retired her to a life of recreational riding. She did love trail rides. At first, I balked at the idea of taking such a spooky, fast horse into wide open spaces far from the relative safety of an enclosed riding ring, but Natalie relaxed so much on the trail, and it was fun to actually let her run like the racehorse she was bred to be.

One day on such a ride, I felt what it must be like down the final stretch of a race. There were three of us: Natalie, a horse named Mansfield (whom Natalie had developed a mare-ish attachment to), and a third horse and rider who tagged along that day. Natalie was used to having Mansfield to herself and spent much of the day keeping him just ahead of her and keeping the other horse behind her, easily done on a narrow trail. Then we reached an open field that would allow a nice gallop. With little urging, the horses were away. Not long after we starting our gallop, Natalie felt the third horse trying to pass her. In one quick action, she moved to the left, stretched lower to the ground, and pushed into warp speed. It was so smooth that I doubt an inexperienced rider would have felt the motion. The horse behind Natalie, even though he was taller and leggier, never caught up.

That was actually one of the last times I rode Natalie. One day, not long after, at a trot in a ring with good footing, she tripped badly on her left hind leg. The diagnosis was bad: equine protozoal myeloencephalitis, or EPM. It’s a progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by a parasite. She needed a spinal tap for the diagnosis, and then expensive daily medicine, dispensed orally in a big syringe. Natalie healed in time, but I decided not to ride her anymore.

In 2000, when we moved to our current home, I moved her to the backyard stable of an ex rodeo rider named Jerry, who’d survived a serious head injury in a training accident. Jerry never recovered his balance and he had to be careful around horses. He taught his small herd to line up at the barn door in a certain order, and then walk to their respective stalls for dinner. As Jerry recounted the story in a shaky voice on Natalie’s first evening at his place, Natalie stayed in the pasture and watched as the other horses lined up waiting for dinner.

Then, Natalie did what Natalie did best. She galloped.

Jerry could see her coming and thought he could stop a hungry, charging, red-haired mare by standing in her path and waving his arms. Natalie sped past and came to a skidding halt in the barn aisle, upending a wheelbarrow. Eventually Natalie settled in and spent her last days there. About a year later, complications from EPM returned, and I knew that she was in a lot of pain. I decided to put her down.

I tell Natalie’s story because all racehorses should have the kind of life, and the kind of death that she had. With help from thoroughbred rescue organizations, some will. Others are left to the scrupulousness or unscrupulousness of their owners.

I’m not even sure it will matter to me if thoroughbred racing manages to ferret out the cheaters. Horses will still break down. Rescue organizations can’t save them all. Why should so many people make so much money from an animal’s willingness to do what we ask, only to be discarded when they’re not good enough?

On Saturday, I will be rooting for California Chrome and every other horse in the race to finish unharmed. And I will be sending out the same tweet I sent this year, and last year: Thoroughbreds run because they love to run. They race because we ask them to. We should stop asking.

Jeanne Erdmann is a freelance health and science writer based in Wentzville, MO. She also co-founded and co-produces The Open Notebook. Follow her @jeanne_erdmann

Images: Jeanne Erdmann. The Jockey Club

Wonderful story about Natalie. I am not necessarily a fan of horse racing but I think that it should be allowed. I wonder if your premise about horses only racing because we ask them. When Natalie took off in a competitive bent against the unnamed horse, it did not appear that you had asked her to. I agree that the abuse that stems from unscrupulous individuals wanting to win at any cost should be detected and stopped. This subject of racing horses (or dogs for that matter) has a lot of interesting ramifications that are not very black and white as PETA would have us believe. Thanks for posting such an interesting story.

Hi David, thanks so much for the comment. Yeah, I spent a lot of time last weekend reading papers from animal geneticists working at a foundation in the UK who are trying to identify genetic variations that would eventually allow breeders to test whether horses would be at risk for some of the most common and devastating leg injuries. If those results clashed with a test that showed the same horse to be potentially really fast, I wonder what owners would do? I guess all sport brings out the unscrupulous. I did learn from the wonderful woman who bred Natalie and so many other thoroughbreds that some just love to race. I just can’t get past the breakdowns.