Joey Pakes was swimming in a cave in Mexico on July 4, 2008 when she spotted her first remipede. Pakes, a graduate student in biology at UC Berkeley, had seen pictures of these aquatic centipede-like creatures before. But when she encountered one in the wild, the experience was completely different. “They’re such graceful animals,” she recalls. “It stopped me and I felt a certain high… I coudn’t scream or go ‘Oh wow, look at this’ because I was underwater. So I was just really happy, and I just shared it with myself and watched it as long as I could. That was my Fourth of July.”

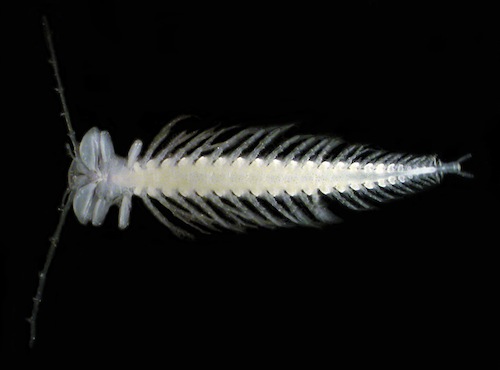

Remipedes are pale, leggy crustaceans, no more than a couple inches long, that dwell in caves filled with layers of saltwater and freshwater. Because these caves are completely dark, remipedes have no eyes. They often swim on their backs, paddling their many legs; their name comes from the Latin word for “oar-footed.”

No one even knew remipedes existed until about 35 years ago, when a teacher named Jill Yager encountered them in a cave in the Bahamas. Since then, scientists have slowly learned more about these creatures’ physiology and behavior. In one 2007 study, researchers observed that remipedes beat their limbs virtually nonstop. They often stayed vertically suspended and waved their antennae, perhaps to filter particles from the water for food. And they occasionally attacked other small animals such as brine shrimp, beginning “with an explosive, ‘jump-like’ motion towards the prey, which was seized… and vigorously shaken, and presumably also stabbed with the maxillules” — sharp mouth parts — “to inject venom,” the scientists write.

Last year, another research team reported that the remipedes’ venom contained enzymes and a toxin to paralyze, soften, and digest their prey. Remipedes deliver this poisonous cocktail by contracting two muscles to shoot the venom out of reservoirs in their mouth appendages. After liquifying the prey’s innards, the remipede can then suck the juices from the animal’s carcass.

Some scientists worry that remipedes are in danger of disappearing before we can learn more about them. For instance, a couple of remipede species live in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, and tourists often visit their caves. Fish take advantage of the divers’ light beams to spot and nab crustaceans. And caves are being polluted by the construction of new resorts.

But even if some remipede species go extinct, others may remain to be discovered. So far, scientists have found remipedes in the Caribbean, Canary Islands, and Australia. Perhaps more of these blind creatures live in dark caves around the world, still unknown, paddling and paddling and paddling.

Image credit: Thomas M. Iliffe, Texas A&M University at Galveston

2 thoughts on “A tiny cave creature, eyeless and deadly”

Comments are closed.