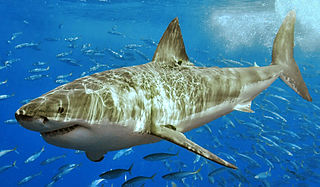

This week, a great white shark named Lydia may be the first white shark seen crossing into the eastern Atlantic. Scientists tagged her a year ago in Florida; since then, she’s swum 19,000 miles and as of yesterday morning, she was about 1000 miles from the Irish coast.

This week, a great white shark named Lydia may be the first white shark seen crossing into the eastern Atlantic. Scientists tagged her a year ago in Florida; since then, she’s swum 19,000 miles and as of yesterday morning, she was about 1000 miles from the Irish coast.

White shark populations, along with those of many other shark species, are dwindling because of bycatch and other threats. The more we can learn about them, the better we can help protect them. But there’s a small part of me that wants to toss a fig leaf over Lydia’s sensor, so that something about her journey is still unknown.

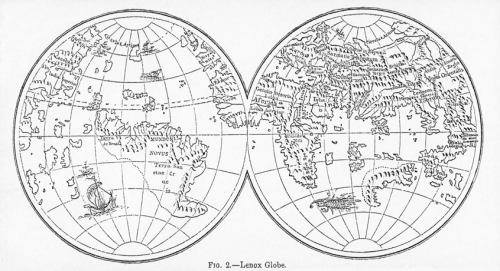

I think that’s one of the things I’ve always loved about marine species, that there’s still so much mystery involved. A lot of species, particularly migrating ones, have been falling off the map for years at various parts of their life cycle. Where do baby sea turtles go once they hatch? Why do migrating eel populations fluctuate so wildly? How do albatross make such long journeys?

I think that’s one of the things I’ve always loved about marine species, that there’s still so much mystery involved. A lot of species, particularly migrating ones, have been falling off the map for years at various parts of their life cycle. Where do baby sea turtles go once they hatch? Why do migrating eel populations fluctuate so wildly? How do albatross make such long journeys?

When I visited a royal albatross refuge in New Zealand in 2005, the literature there described the veil that fell over the young albatross’s flight after it departed from the Otago Peninsula. I loved the idea of these big-winged birds soaring off, fade to black…until they returned to breed. Now, at least one study has followed young northern royal albatross with GPS as they took wing to Chile; many are also known to stay a hundred miles or more offshore by the Patagonia Shelf to find food, or make circumpolar rounds in the southern ocean.

Researchers now know much more about just-hatched sea turtles setting out from Florida. These baby turtles were fixed with flexible solar-powered satellite tags (with a little extra help from one of the researcher’s manicurists, who’s thanked in one of the group’s papers—they applied a base coat of nail acrylic to get the transmitters to stick for several months). With the help of these tags, many of these once-elusive turtles have been found in the Sargasso Sea, where mats of seaweed may keep these cold-blooded youngsters warm.

Researchers now know much more about just-hatched sea turtles setting out from Florida. These baby turtles were fixed with flexible solar-powered satellite tags (with a little extra help from one of the researcher’s manicurists, who’s thanked in one of the group’s papers—they applied a base coat of nail acrylic to get the transmitters to stick for several months). With the help of these tags, many of these once-elusive turtles have been found in the Sargasso Sea, where mats of seaweed may keep these cold-blooded youngsters warm.

And then there are the eels. They’re born in the Sargasso Sea, and the young eels, known as elvers, take two years or so to make it to rivers in Europe. Using ocean models, researchers found that wind-whipped currents play a key role in how many eels arrive each year.

All these studies are important in determining how these species are faring, and how to help. For the endangered eels, fisheries managers could determine whether to limit catch sizes for eels, based on how well migrators fared. Or they could let local fishermen know when to take a pleasure cruise at night, through eel-infested waters. (Sorry, sorry, couldn’t help it! That’s the first thing I think of when I think of eels.)

I know this isn’t the end of mysteries. There are plenty of things about these species and many others still left to be discovered. Perhaps it’s just that a solved mystery makes a satisfying end to a story, so we hear more about the answers than we do about the questions that remain. Or maybe it just says something about me—that I’m the one who’d like to fall off the map for a while, at least until I find my way home.

**

Images Kattigara‘s Lenox Globe, César‘s white shark, NOAA‘s loggerhead sea turtle–all via Wikimedia Commons

We often talk about wilderness, and it is possible here in Australia to get a long way from it all. But the truth is that our last true wildernesses are found in our oceans.