If you were a kid in the eighties in California, you might have done things like this: Save the bathwater and flush the toilets with it. Turn off the shower when you soaped up. Let it mellow. You might have even had a Rube Goldberg-like contraption like the one my dad made to use water from the washing machine for the plants. Maybe, like me, you got embarrassed when you saw the signs that read “Save Water. Shower with a friend!” We were all drought experts then. In my freshman dorm, my roommate even policed other people’s sinks while they brushed their teeth.

If you were a kid in the eighties in California, you might have done things like this: Save the bathwater and flush the toilets with it. Turn off the shower when you soaped up. Let it mellow. You might have even had a Rube Goldberg-like contraption like the one my dad made to use water from the washing machine for the plants. Maybe, like me, you got embarrassed when you saw the signs that read “Save Water. Shower with a friend!” We were all drought experts then. In my freshman dorm, my roommate even policed other people’s sinks while they brushed their teeth.

Only then the drought was over. And it’s been so easy to forget.

A friend who lives in D.C. asked me what it’s like in California right now. And here is the problem—for me, anyway. It’s not that different. Turn on the tap and water still comes out. Hot water, cold water, a lot of water, whatever kind of water you want.

Sure, I’ve noticed things. We went to the Sierra Nevada in January—named for their rugged snowiness–and there wasn’t any snow, and the mountain lake that we swim in during the summer looked like a lunar landscape. On the way home, crossing through the Central Valley, hills that might be green–at least greenish–in winter were the color of an old paper lunch sack. Billboards along farm fences lambasted the politicians thought to be responsible for the water crisis. Closer to home, old ghosts appear as our reservoir dwindles—a WPA-era bridge, the foundations of a long-ago ranch, islands that aren’t islands any more.

Still: turn the tap on, water comes out.

Even though my day-to-day life doesn’t seem affected yet, plenty of other people’s are. Communities are scrambling. Farmers are steeling themselves to tear out crops and lay off workers. Already-endangered salmon are in a holding pattern in estuaries and river pools. If they don’t make it upstream, that’s another year of salmon gone.

And then there are people like me, who the drought doesn’t seem to be affecting today. Maybe not even this winter. But you never know. During the last drought, the hills got thick with dry brush and grass and leaf litter, and eucalyptus trees stood dead after a winter freeze. A few months before the rains that signaled the end of the drought, a massive fire destroyed more than 3,000 homes and killed 25 people in Berkeley and Oakland.

We stopped saving bathwater after the fire, and the washing machine in our new house was only ever a washing machine. We could only deal with the current crisis, it was too much to think about another one.

But that’s exactly what we need to do, says Brian Stranko, who directs The Nature Conservancy’s California Water Program. We’ve got to get ready for the droughts to come.

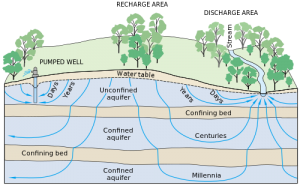

Stranko thinks one of the state’s big hopes is its groundwater. I called him in the first place because I got an email highlighting the connection between groundwater and the drought. And even though a description of the hydrologic cycle somehow made its way into our wedding ceremony—much to the amusement of those assembled–the first thing I thought was: how does groundwater have anything to do with the drought? It still just needs to rain.

This is what he said: California’s geology means it has enormous reserves—or at least, the potential for reserves—of underground water. We’re already tapping into it; in much of the state when we need more water, we dig another well, dig deeper into wells we already have, and pump more water out.

During a regular year, groundwater pumping increases steadily. “During a drought—bam!–it’s a huge surge. And you don’t have much choice,” he says, when you don’t have anything to fall back on.

TNC and other groups, including several water districts, are working on ways to better manage groundwater in anticipation of future dry spells. One thought is to treat these groundwater sources—the ones that remain, in any case, as some have already been tapped out to the extent that the land has started sinking—like we would a reservoir. We’d figure out what level they needed to stay at to be sustainable; if they started to dip, we’d have to make some tough choices about how to dial back the outflow.

I don’t know if this is an answer, of course I don’t. I only know how to dip a pail in the bathtub, to let it mellow, to shower with a friend. But it does seem like we need to come up with more reserves, whether beneath our feet or within ourselves, to deal with this thing that we know is coming, this thing that we still never can quite see before it’s here.

**

Image of dry California riverbed from NOAA; groundwater graphic from USGS, both via Wikimedia Commons

…this thing that we do not want to ever see, that is the problem, denial. Thanks for bringing up the discussion, only then can we begin the quest to figure out the unimaginable.

I am a native of Central California and only recently moved away to the Pacific Northwest for grad school. When I was visiting home during the holidays it was shocking how brown things were. Even more shocking where fields in which you could see salt in the soil, in December!

I think the problem in recent times is drought has become so political. People don’t realize that the lack of water this year is from the actual lack of rain and lack of snow pack in the Sierra Nevadas that supply the reservoirs we rely on. Instead, people are blaming the government for diverting water from them. There is no water to divert! It is a frustrating situation and it is going to be a long summer of bad news for Californians. (I almost feel guilty now living in a place that can get more rain in a few days than Central California gets in a year.)

Thanks, thefolia and Liz. Liz, I had a similar experience–we lived in Oregon for several years and it was so strange (and guilt-inducing) to be in a place where water was so abundant.