Behind science news stories, which are facts or predictions of facts, is a reality which gives them their context and sometimes their meaning.

Behind science news stories, which are facts or predictions of facts, is a reality which gives them their context and sometimes their meaning.

Science magazine, January 23, 2014: “A new analysis . . . indicates that modern-day rumblings in the New Madrid Seismic Zone are not echoes of the 1811 to 1812 quakes, however. Instead, they are signs the seismic zone is still alive and kicking.”

Like New Madrid, Missouri, my home in Baltimore, Maryland is in the stable center of the stable North American plate. Earthquakes don’t happen here, except when they do. July 22, 2010, a little magnitude 3.6 earthquake rumbled through my bedroom and back out again, I woke up, thought “Oh, earthquake,” and went back to sleep. August 23, 2011, a much bigger magnitude 5.8 earthquake rumbled into my office building, stuck around for a bit, left, then came back and rumbled around some more. The four-story 19th century brick factory building shimmied, it shuddered, and I was viscerally afraid. Like when I was a kid in the cellar because the radio was saying a tornado was coming and the air was thick, the sky was dark, the winds in the clouds going crazy and tearing apart the black clouds to show their green insides. Whatever is happening, it’s big. And I’m small, soft, and easily smashed, and I’m afraid. I’m so afraid.

December 16, 1811, a really big magnitude 7.7 earthquake hit New Madrid. Another one, magnitude 7.5 hit on January 23, 1812. A third one, magnitude 7.7, hit February 7, 1812. Buildings and people weren’t much damaged because hardly anyone lived there then. The ground rose, sank, and cracked. Waves on the Mississippi River overwashed boats; islands disappeared; and the great river itself changed course.

December 16, 1811, a really big magnitude 7.7 earthquake hit New Madrid. Another one, magnitude 7.5 hit on January 23, 1812. A third one, magnitude 7.7, hit February 7, 1812. Buildings and people weren’t much damaged because hardly anyone lived there then. The ground rose, sank, and cracked. Waves on the Mississippi River overwashed boats; islands disappeared; and the great river itself changed course.

Elisa Bryan, New Madrid, 8 February, 1812: “A concussion took place so much more violent than those that had proceeded it. At first the Mississippi seemed to recede from its banks, and its waters gathering up like a mountain. It then rising fifteen to twenty feet perpendicularly, and expanding at the same moment, the banks were overflowed with the retrograde current, rapid as a torrent. The river falling immediately, as rapid as it had risen, receded in its banks again with such violence, that it took with it whole groves of young cotton-wood trees, which ledged its borders. In all the hard shocks mentioned, the earth was horribly torn to pieces.”

Mid-plate earthquakes don’t stay local, they travel. The New Madrid quake woke people up in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Charleston, South Carolina. People in Louisville, Kentucky were especially frightened.

George Heinrich Crist, Nelson County, Kentucky, 16 December, 1811: “There was a great shaking of the earth this morning. You could not hold onto nothing neither man or woman was strong enough – the shaking would knock you lose like knocking hicror nuts out of a tree. I don’t know how we lived through it. None of us was killed – we was all banged up and some of us knocked out for awile and blood was every where. We will have to hunt our animals. Every body is scared to death. I made my mind to one thing. If this earth quake or what ever it was did not happen in the Territory of Indiana then me and my family is moving to Pigeon Roost as soon as I can get things together.”

23 January 1812: “What are we gonna do? You cannot fight it cause you do not know how. It is not something that you can see. The earth quake or what ever it is come again today. It was as bad or worse than the one in December. We lost our Amandy Jane in this one – a log fell on her. We will bury her upon the hill under a clump of trees where Besys Ma and Pa is buried. A lot of people thinks that the devil has come here.”

8 Febuary 1812: “If we do not get away from here the ground is going to eat us alive. We had another one of them earth quakes yesterdy and today the ground still shakes at times. We are all about to go crazy – from pain and fright. I do not know if our minds have got bad or what. But everybody says it. I swear you can still feel the ground move and shake some.”

Crist’s mind hadn’t gone bad: between the earthquakes and after them for a long time were many aftershocks. Ever since then, geologists have been trying to figure out what happened and whether it could happen again. New Madrid turned out to be at the frangible tip of a ancient rift being torn in an ancient continental plate. The considerable number of small aftershocks have continued to the present, but geologists thought they were only echoes of the big earthquakes and that the rift-torn faults had shut down.

But a new study just said the faults are not dead, they’re still active. The number of aftershocks from any earthquake falls off in a predictable way and since 1812, New Madrid should have felt 135 significant, magnitude 6 aftershocks; instead, it’s had only 2. “Something is going on there,” says one of the study authors. They think it might be stress accumulating for a new earthquake. Other geologists argue with this: mid-plate earthquakes are exceptions to the rules of prediction, and nobody’s detected strain building up. But today nearly 3 million people live in the area. And for now the possibility is still on the table: the river could change course again, the ground could still eat people alive.

Eliza Bryan, 22 March, 1816: “We were constrained by the fear of our houses falling to live twelve or eighteen months, after the first shocks, in little light camps made of boards; but we gradually became callous, and returned to our houses again. Most of those who fled from the country in the time of the hard shocks have since returned home.”

George Heinrich Crist: 14 April 1813: “We lived to make it to Pigeon Roost. We did not lose any lives but we had aplenty troubles. As much as I love my place in Kentucy – I never want to go back.”

_____

Dedicated to my cousins Kim and Guida, who each lost their homes and nearly everything else in the November 17, 2013 tornado.

I edited both Ms. Bryan and Mr. Crist for length.

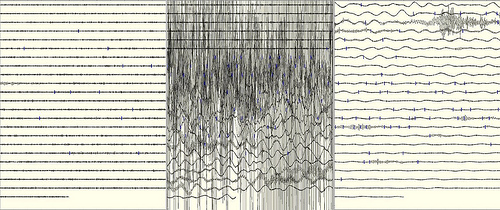

I cropped Séisme for earthquakiness – photo by Denis Collette…!!!

seismogram of Japan earthquake, magnitude 9 (nine!) – uair01