Halton Arp — “Chip” to his friends — died in Munich on December 28, 2013, and with him a cosmological banner has fallen to the ground. It’s a banner that younger astronomers may choose to take up. If they do, however, they should be cautious: it could mean the end of their careers. As a graduate adviser once remarked to me, “Any student or astronomer who pursues Arp’s work is asking for it.” Why? Because when it comes to standard cosmological theory, Arp is, or was, a renegade of the first order.

Halton Arp — “Chip” to his friends — died in Munich on December 28, 2013, and with him a cosmological banner has fallen to the ground. It’s a banner that younger astronomers may choose to take up. If they do, however, they should be cautious: it could mean the end of their careers. As a graduate adviser once remarked to me, “Any student or astronomer who pursues Arp’s work is asking for it.” Why? Because when it comes to standard cosmological theory, Arp is, or was, a renegade of the first order.

Quasars, he claimed, are not the highly energetic cores of very distant galaxies that astronomers declare them to be. They are actually fairly nearby, and ejected from active galactic nuclei. The big bang? Never happened. The universe, as his colleagues Geoffrey Burbidge and Fred Hoyle also contended when they were alive, has always been here in a steady state of existence. The cosmic microwave background radiation? That’s not the afterglow of the big bang fireball, it’s the limiting temperature of space heated by all the stars in all the galaxies in the universe. In the minds of conventional astronomers, these are the thoughts of an apostate, a heretic, a crank, and a crackpot, and Arp was called all these names and more. “Stay away from that lunatic,” an astronomer once pointedly warned me.

But I didn’t stay away. In fact, I and fellow free spirit Dennis Webb wrote a book about Chip Arp, called The Arp Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies: A Chronicle and Observer’s Guide. In part, it recounts how Arp the astronomer came to be Arp the iconoclast, a story full of academic intrigue and astronomers not playing well together. But what we really wanted to do was commemorate his singular Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies.

Published in 1966 by Caltech, the APG remains a kind of cabinet of galactic curiosities. It contains 338 photographs of galaxies, but not the symmetrical spirals and ellipticals we are all familiar with. Rather, these are uncanny and tortured-looking systems that exhibit some astonishing malformations: plumes, shells, conjoined amorphous masses, and filaments of matter trailing away from the galaxy’s main body.

For young astronomers at the time, seeing all these galactic pathologies in one place challenged their preconceptions of what a galaxy truly is. At the time the APG was published, Edwin Hubble’s galaxy classification scheme was being refined and others were being proposed. But galaxy classification in those days largely concerned itself with the more symmetrical forms — the spirals, spheroidal ellipticals, and lens-shaped lenticulars. Of course, astronomers were aware of galaxies that were, in essence, unclassifiable, but they amounted to less than 2 percent of the known galaxies and, as such, were generally ignored. Arp’s APG, however, wasn’t something any astronomer could afford to disregard.

In those days, as now, astronomers were trying to figure out what makes a galaxy look the way it does. The peculiar galaxies, it turned out, held some of the answers. Back in the mid 1950s, it was thought that, given the vast volumes of space between galaxies, seeing any two in the process of colliding would be exceedingly rare. Observations in 1954 by Walter Baade and Rudolph Minkowski challenged that perspective when they confirmed that the radio source Cygnus A was, in fact, two galaxies in actual collision. Still, most astronomers remained skeptical even after the APG was published. Today, of course, computer simulations have clearly demonstrated that mergers, near passes, and collisions are responsible for endowing peculiar galaxies with their extraordinary features. Insofar as an explanation exists for their bizarre shapes, peculiar galaxies are no longer peculiar.

By the mid-1990s, when galaxies in the early universe began emerging from the shadows in deep image surveys, it became apparent that not a single one could be deemed normal. Moreover, astronomers were forced to conclude that all of the normal galaxies in the nearby universe — including our own — evolved from these primeval masses.

Arp’s atlas showed that galaxies near and far were not like dead butterflies pinned to a taxonomic display board, but constantly evolving, changing, dynamic systems. It also demonstrated one of Arp’s premises: that when looked at closely enough, all galaxies — even the normal-looking ones — are peculiar. To test this assertion, just look at a single galaxy at different wavelengths.

For now, it seems the professional astronomy community chooses to ignore Arp’s earlier accomplishments with respect to galaxy classification because that work was subsequently overshadowed by his contentious theories about quasar ejections and the big bang (or lack thereof). I think, however, that an argument can be made for recognizing someone for his or her rightfully earned successes, and letting any alleged controversies slide. In compiling the APG, Chip followed both his instincts and the scientific process to their empirical conclusions, and the result was an invaluable contribution to galactic research that even conventional astronomers can embrace. My personal opinion is that, in some way, he should be formally recognized for this work.

What difference does it make now that he or Burbidge or Hoyle — the last of the elderly radicals — may have been wrong about the steady state and the origins of quasars? After all, as Chip once replied to Jan Oort, who wrote him urging him to give up his radical ways, “If you’re wrong it doesn’t make any difference, but if you’re right, it is terribly important.” About peculiar galaxies, he was right.

• • •

Jeff Kanipe is the author of several popular books on astronomy, including, most recently, The Cosmic Connection: How Astronomical Events Impact Life on Earth. He is also coauthor, with his wife Alexandra Witze, of the forthcoming book Island on Fire, which chronicles the disastrous 1783 eruption of the Icelandic fissure volcano, Laki.

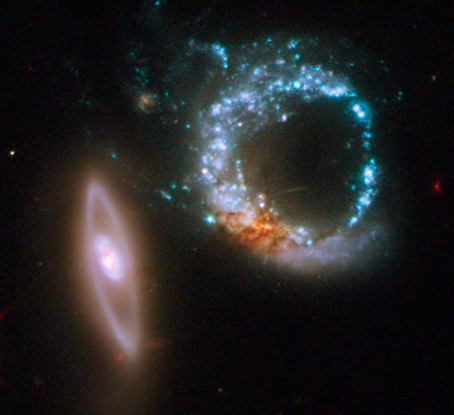

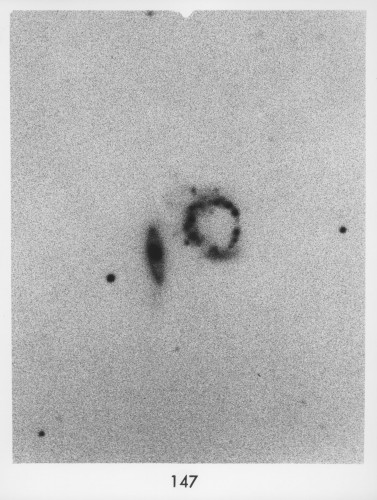

*Images: The two photographs show the same object, a pair of interacting galaxies called Arp 147. The upper image was made by the Hubble Space Telescope; the lower is from Arp’s Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies. Arp 147 consists of a relatively undisturbed, nearly edge-on disk galaxy (at left) that has punched out the center of what is now a ring galaxy (at right). The disturbance has touched off a ring of star formation (the blue knots in the upper image).

Fascinating article! I think the argument that Arp deserves recognition and acknowledgement is a strong one.