Fear of insects is so common that it’s hardly worth remarking on. It’s those of us who don’t fear bugs who can seem a little odd.

Fear of insects is so common that it’s hardly worth remarking on. It’s those of us who don’t fear bugs who can seem a little odd.

Science and nature illustrator Maayan Harel told us recently that while she’s acquired an appreciative fascination with her insect subjects, acquaintances still ask, with a shudder of disgust: “Are you still drawing those bugs?”

Actually eating bugs (and then flossing their bristly little legs out of one’s teeth, as Sally did not long ago) is usually seen as either a courageous, taboo-busting act or just nuts.

And we accommodate entomophobia as a matter of course. Rebecca Boyle, who writes the Eek Squad blog for Popular Science, recently added what she calls a “hide-gross-bug” button to her posts so that squeamish readers can avoid disturbing photos like the one above (sorry). Fears of heights and needles are also extremely common, but we don’t provide a “hide-scary-view” button in skyscrapers, and we’re all still expected to bare our arms for puncturing.

Entomophobia, in fact, is only remarkable when the sufferer is an entomologist.

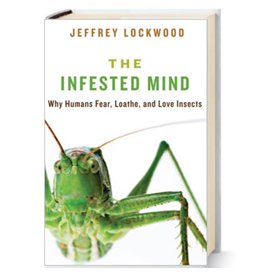

A few years ago, entomologist Jeffrey Lockwood was checking on one of his study sites, a small canyon in Wyoming known for its prolific grasshoppers. He’d never feared insects — on the contrary — but as he entered the canyon, the grasshoppers carpeting the ground rose up and swarmed him. In his new book The Infested Mind, he writes:

Grasshoppers boiled in every direction, ricocheting off my face and chest. Some latched on to my bare arms and a few tangled their spiny legs into my hair. Others began to crawl into my clothing — beneath my shorts, under my collar. They worked their way into the gaps between shirt buttons, pricking my chest, sliding down my sweaty torso. For the first time in my life as an entomologist, I panicked.

The fear he experienced that day returned sporadically, and Lockwood began to worry that he would embarrass himself in front of students or colleagues. Worse, he felt his scientific objectivity was compromised: The very organisms he hoped to understand were clouding his mind with panic.

In The Infested Mind, Lockwood directs his curiosity toward his own fears, and in the process unpacks the surprisingly complex reasons for our fear of insects.

In The Infested Mind, Lockwood directs his curiosity toward his own fears, and in the process unpacks the surprisingly complex reasons for our fear of insects.

On the surface, entomophobia seems pretty rational: lots of bugs bite and carry disease, so people who avoided them in the past probably survived longer and reproduced more, meaning that we’ve probably evolved to fear bugs. Right? But mosquitoes are among the most dangerous disease-carrying insects, and they usually don’t scare or disgust us nearly as much as, say, cockroaches.

There may be some hard-wiring involved, but we learn a lot of our entomophobia — from unfortunate childhood experiences with beehives or anthills, from our parents, or from the culture at large. “We are weevils/We are evil/We’re aggrieved/Since time primeval,” begins a poem in Douglas Florian’s Insectlopedia. Read that at bedtime for a few nights, parents, and you’ll have a thriving little entomophobe on your hands.

While Lockwood thoroughly dissects the biology and psychology of our infested minds, he can’t explain away his own fears. In the years after his encounter in the Wyoming canyon, he moved out of traditional scientific research and into work that combines science and the humanities — an intellectual evolution that he credits in part to his phobia. He has come to a sort of peace with his fear, learning to see it not as a handicap but as a reaction to the sublime. For most of us, he points out, a skittering insect is as alien as the open space at the edge of a cliff, and we’re repelled by it and drawn to it in a similarly paradoxical way.

So next time you floss a cricket leg out of your molars, remember: It’s not disgusting. It’s sublime.

Madagascar hissing cockroaches photo courtesy of Flickr user Hopefoote. Creative Commons.

My two-year-old twins are fascinated by insects, and it’s because I always point at them and explain what they are and what they are doing. We learn many of our fears directly from our parents. Certain insects are “scarier” than others, as well: very few people are scared of butterflies or ladybugs, and ladybugs are beetles just like roaches are. It’s a fascinating topic, but many of our fears are cultural, not rational.

I appreciate Josie’s thoughts–and I think that she’s right about the importance of parental messages. In my book, I suggest that we are evolutionarily attuned to keenly attend to insects, but once they have our attention, cultural messages play the dominant role in shaping our positive or negative responses. And I’d mostly agree with Josie about fears and rationality, except that I think that many of our fears are reasonably derived and the problem comes when they become irrational (one of the features of a genuine phobia). And finally, a couple of small points. Cockroaches aren’t beetles (Coleoptera); they belong in a different order (Blattodea) which, of course, isn’t a reason to fear them. And oddly enough, there are people with mottephobia, an irrational fear of moths (not quite butterflies, but creatures that most of us would not find terrifying).

I was so relieved when I discovered mottephobia was a real — if irrational — phobia. It is embarrassing to admit, but I am terrified of moths. I mean run-across-the-room shrieking, goose-bump-inducing, arm-waving TERRIFIED. I blame the miller moth infestation of Colorado in 1989. I was scarred for life by the sight of moths flying out of my closet in the morning light.

Maybe their erratic flight patterns cause fear? To me, it’s that plus their plump midsections. Butterflies are thin and graceful, and I’m not afraid of them.

Oh… I have the chills just thinking about them!

Oh wow! I thought I was the only person who was afraid of moths (and have many people make fun of me for it). So interesting to learn there’s even a word for it. Like Rebecca, I think it’s the fluttery flight that bothers me. But butterflies bother me too — just not quite as much.

I’ve learned to control my fears somewhat and am hoping not to share them with my children.

Thank you for this! I’ve added Jeff’s book to my Christmas wish list, not least because I am actually working on an article on this exact topic!

Seems like my personal experience has been a gradual transition in the opposite direction…I grew up pretty panicked over spiders (genuine phobia, I think). This was most definitely related to my mother’s lifelong arachnophobia. It wasn’t until I was doing my undergrad degree, and spening a lot more time in the mountains (recreational and academic reasons), that I began to gain a more balanced perspective on spiders. I later in university did a 32 benthic macro invertebrates illustration contract that further opened my eyes to the wonder of insect ecology. Today, I’m the one gently intervening when little cousins try to squash moths – I vividly recall one moment when a budding waist-high naturalist leaned in and his “kill it!” changed to curiosity and wonder and a multi-year self-directed study of Montana’s butterflies and moths. Several more little ones clustered around, wondering why we were staring so intently at a garage wall. Perhaps the highlight of the situation was when some parents wandered over, and the little ones began proclaiming the wonders of moths to them.

Bottom line, I think a fundamental element of various “ecophobias” is lack of positive experience with various aspects of nature.

Dear Jeff: Thanks for pointing out that roaches are not beetles. I realized how important parental messages are when my kids saw a roach scuttle under a cabinet and started discussing what it was doing: “Where did the beetle go? The beetle is hiding,” and so on. I should add that I am not a fan of roaches, particularly, although I have written a book about insects (“Buzz: The Intimate Bond Between Humans and Insects”) so I’m probably more open-minded than most.

Several years ago, I was visiting in St. Louis and went to the Missouri Botanical Garden (highly recommended) ( also highly recommend their web site: http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/ especially the “Plant Finder” section). My daughter-in-law raises bees and was studying an exhibit of a plastic covered hive which showed the bees in action live. 3 children dashed over to check out the moving bugs, and Jessi told them about what was going on, but one remark made a special impression, as I heard one say excitedly as they were leaving with their mother: She said that if you don’t bother bees they mostly won’t sting you because they are too busy.