Yesterday I related the official version of how photons from the star Arcturus triggered an electrical signal that lit up the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. My research into that event, however, has sent me deep into the weeds.

Most historical accounts claim that four observatories — Yerkes, Harvard College, Allegheny, and the University of Illinois — participated in the lighting event. The proceedings of the ceremony itself testify to this. On the rostrum, a 60-foot-tall board of switches and relays depicting the four geographical locations dramatically lit up one by one as they transmitted their Arcturian signals to the Fair. But in an article that appeared a couple of days prior to the event in the University of Chicago Magazine, the incoming Yerkes director Otto Struve wrote: “In case of cloudy weather several other observatories have been invited to keep their telescopes in readiness [author italics], so that they may substitute for the Yerkes Observatory refractor.” That’s a slight contradiction to the way the ceremony played out that night. Was Struve simply mistaken, or astonishingly out of the loop?

By itself this would not be too much of a concern if the skies at Yerkes had been clear — but were they? Opening night in Chicago, just 70 miles to the south, was reported by several sources as overcast with light rain. Fox even alluded to the cloudy skies in his speech: “Were it only clear, we could look into the sky and see the star Arcturus.”

Still, it is meteorologically possible that Yerkes was in the clear, or briefly so. As evidence, we have a telegram Struve sent the following day to L. R. Lohr, general manager of the Century of Progress: “Pleased to know that ceremony was a success in Chicago STOP Sky cleared up just in time for performance and clouded over half an hour later STOP.” In his chronicle of that evening at Yerkes (Yerkes Observatory: 1892-1950), astronomer and historian Donald E. Osterbrock confirms “It was cloudy in Chicago that night, but luckily it was clear at Williams Bay.” Then, however, he cryptically adds a parenthetical aside: “. . . or perhaps it was cloudy but Elvey shone a flashlight up on the dome.” (“Elvey” refers to Christian T. Elvey, an astronomer who was operating the telescope that night.)

Of course, the astronomers would know that photocells were sensitive enough that a flashlight would have activated them. Perhaps the “flashlight solution” was a backup plan in case of clouds. But if it weren’t, then why would Osterbrock — known for his meticulous historical research — refer to someone (by name, no less) shining a flashlight on the dome at Yerkes if it didn’t actually happen? In fact, why mention it at all? The only explanations I can see are that either it really happened that way, or Osterbrock was making a little joke.

Of course, the astronomers would know that photocells were sensitive enough that a flashlight would have activated them. Perhaps the “flashlight solution” was a backup plan in case of clouds. But if it weren’t, then why would Osterbrock — known for his meticulous historical research — refer to someone (by name, no less) shining a flashlight on the dome at Yerkes if it didn’t actually happen? In fact, why mention it at all? The only explanations I can see are that either it really happened that way, or Osterbrock was making a little joke.

In trying to get to the bottom of all this, I consulted the Yerkes archives housed at the University of Chicago Library. Box 143, folder 7 contains news clippings and correspondence related to Yerkes’ participation in the Arcturus lighting ceremony. I found no smoking flashlight, but with the help of an agreeable research assistant, I came across a few other intriguing behind-the-scenes tidbits that may or may not be relevant to this mystery.

For example, Struve complained to Philip Fox about the Fair administrators’ repeated attempts to get the observatory to repeat the ceremony. Not only is it “quite a job to put the instrument on the telescope and take it off,” but the “exceedingly bad weather conditions that we have been having this spring” made him “especially loath to devote any more time to the Arcturus stunt.” (Notice Struve’s use of the word “stunt.” Initially, he had not been enthusiastic about the lighting ceremony, considering it more bombastic performance than science. His enthusiasm, however, increased tremendously when he learned from Fox that the Fair’s general manager had promised Yerkes three percent of any potential surplus of the Fair’s receipts.)

Apparently the Fair administrators had more luck in gaining cooperation from Allegheny Observatory director Frank Jordan. On June 3, he admitted to Struve that Allegheny had been continuing to send signals to the Fair but “only by making the contact with a telegraph”—essentially, simply sending electricity by pressing a telegraph key rather than going through the bother of relaying photons from Arcturus.

One other important clue supports the case that the lighting ceremony didn’t go as planned that night. Fox’s granddaughter, Ann Fox Gulbransen, told me in an email that she remembers her father saying that his father (Philip Fox) told him that it was cloudy at all the observatories that evening. “I believe that they all pointed the telescopes at the point in the sky where they knew Arcturus was behind the clouds and called that ‘close enough.’ I expect that not many people know that!”

Welcome to my weed patch. Clearly, this little story — handed down for some 80 years — has some unresolved issues. There are others, including the account of one Ralph Mansfield, employed at the time as a guide at the Adler Planetarium, who, in 2004, came forward to say that it was he who activated the Fair’s lights by training one of the planetarium’s telescopes on to Arcturus at the last minute. Presumably, that telescope would have been equipped with its own cumbersome photocell, photometer, and transmission equipment.

What really happened? I think that, barring new revelations, the truth about the Arcturus lighting ceremony may never fully be revealed. All the participants, along with Osterbrock, are safely deceased. If you ask me, though, I suspect that there was a guy armed with a flashlight on the grassy knoll; Osterbrock found out about it and, not wanting to cast aspersion on Yerkes (who would?), simply glossed over the truth with a sotto voce remark. Or maybe not. I don’t plan on giving up, though, in any case. There must be more to this story, and too many good stories about science begin in the weeds.

* * *

Jeff Kanipe is the author of several popular books on astronomy, including, most recently, The Cosmic Connection: How Astronomical Events Impact Life on Earth. He is also coauthor, with his wife Alexandra Witze, of the forthcoming book Island on Fire, which chronicles the disastrous 1783 eruption of the Icelandic fissure volcano, Laki.

The author would like to thank Tom Whittaker, reference assistant in the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Chicago, for searching through the Yerkes archives for material relevant to this story.

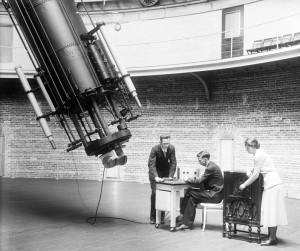

Images: The Hall of Science, courtesy of Century of Progress Records, 1927-1952, University of Illinois at Chicago Library; astronomers Christian T. Elvey (seated), Paul Rudnick (standing), and Helen Pillans (manning the radio) on May 27, 1933, at the business end of the Yerkes 40-inch refractor, courtesy of the University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center, apf6-00458.

Sources:

Cheryl R. Ganz, The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress (University of Illinois Press, 2012).

Donald E. Osterbrock, Yerkes Observatory, 1892-1950: The Birth, Near Death, and Resurrection of a Scientific Research Institution (University of Chicago Press, 1997): pp. 137-138.

Otto Struve, “Arcturus and the Century of Progress,” University of Chicago Magazine, 25 (1933): p. 312.

Edwin Brant Frost, An Astronomer’s Life (Houghton Mifflin, Co., 1933): p. 256.

Email from Ann Fox Gulbransen to Jeff Kanipe, May 2, 2012.

Trevor Jensen, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-12-21/news/0712200868_1_adler-planetarium-observatories-lights

I hope you post again here, should you come up with further evidence for either side of the “argument”.