Magicians scare me.

Not magic. Magic is cool. I was at a party recently when I asked someone what he did and he said he was a magician and I said I hope he didn’t mind but would he possibly—and even before the request was out of my mouth he had produced a deck of cards. We cleared space on the bar in a corner of the room, and soon a crowd had gathered. The impromptu show was typically mind-blowing. I loved the act. But when it was over and the magician and I resumed our conversation, I realized I was nervous.

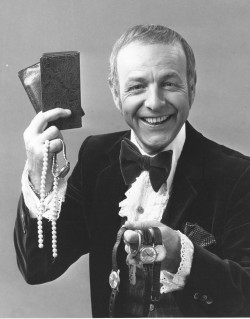

The magician turned out to be Alex Stone, a former writer for Discover, an aspiring physicist who eventually dropped out of the PhD program at Columbia University in order to pursue magic, and the author of Fooling Houdini: Magicians, Mentalists, Math Geeks, and the Hidden Powers of the Mind (out in paperback today). He was kind enough to send me his book a few days after we met. I confess I opened it with a combination of fascination and dread: fascination, because I might find out how magic fools me, and dread because I might find out how magicians fool me.

I thought a lot about my relationship to magic and magicians in the days following that party. Part of my fascination with magic, I finally decided, had a scientific side to it. Magic appears to break the laws of nature. Objects pass through solid surfaces, signed cards appear inside unopened decks, bifurcated women become whole. We know that the magicians aren’t breaking the laws of nature; we know there’s a trick to it, whatever the impossible “it” is. We don’t fall to our knees and worship the magicians for their ability to bend nature to their will. (Though Stone has an intriguing aside in his book: Was Jesus a magician, and his miracles conjuring tricks?) We just want to know, How’d they do that?

They won’t tell, of course. The magician’s code and all that. Stone himself received significant pushback from the magicians’ community after he published an article in Harper’s in 2008 that revealed some of the tricks behind the tricks of his trade. While he’s more circumspect in his book, he nonetheless argues that you can’t really violate the code if the “secrets” are already freely available on the internet. You want to know how David Copperfield made the Statue of Liberty disappear? The answer is a couple of clicks away. (I’ll save you the trouble.) The solution is—as the solutions to illusions often are—ingenious. When I find out the solution to an illusion, my response almost always is an intellectually fizzy My brain just doesn’t work that way.

Which brings me to my fear of magicians. While we know they’re not breaking the rules of nature, we also know that we’re powerless to stop them from appearing to break the rules of nature. If we don’t know the secret behind the illusion, they can easily fool us. Sometimes even if we do know the secret behind the illusion—sometimes even if we’re magicians—they can still fool us. My suspicion as I began reading Fooling Houdini, given the author’s background in physics, was that he would have a scientific explanation for how magicians deceive us. He did, and it did nothing to ease my discomfort: Because nobody’s brain works that way.

“In magic,” he writes, “when people fail to spot the secret to a trick, they tend to blame their vision, invoking the age-old saying ‘the hand is quicker than the eye.’ In fact, the human eye is a blazingly efficient instrument capable of spotting flashes of light as brief as 1/100th of a second, the shortest time interval on a digital stopwatch. A mere five photons—or quanta of light—are sufficient to trigger a conscious visual response.”

But it’s the subconscious response that’s the key to selling the trick.

We all know that magicians use misdirection—visual cues that get us to look where they want us to look, which is to say, not where we should be looking if we want to see how the trick is done. But often misdirection isn’t necessary, or is at best an accessory to what’s really fooling the mind: inattentional blindness.

I once encountered this phenomenon first hand—or first wrist, I should say. A close-up magician entertaining at a dinner party asked me to volunteer for a trick. He held both my hands, said or did something about a coin (it doesn’t matter which), then let go. A few minutes later he asked me for the time. I had lost my watch—and he was wearing it.

Stone cites a 2005 study by psychologists Gustav Kuhn and Benjamin Tatler describing an experiment in which a magician “vanished” a cigarette by dropping it into his lap. Using eye-tracking tools, Kuhn and Tatler found that even those subjects who were looking directly at the cigarette as it fell into the magician’s lap didn’t consciously see it. “The image enters our pupils,” Stone writes, “strikes the retina, and barrels down the optic nerve all the way to the brain”—but the brain doesn’t consciously perceive it because it’s thinking about something else. (Probably most people reading this site have seen the count-the-basketball-passes video that illustrates this phenomenon, but if not, you’re in for a treat.) “Magicians employ misdirection,” Stone writes, “to force us into multitasking mode, thereby inducing a temporary state of impaired awareness.”

Magicians don’t just get us to look elsewhere. They get us to think elsewhere. And while we’re thinking elsewhere, we miss what’s going on right in front of us. Forget the idea that the hand is quicker than the eye. As Stone says, “The hand is quicker than the mind.”

There, I think, is the problem, at least for me. The magician who lifted my watch had distracted me with a trick I thought he was performing—the thing with the coin—so that he could perform the real trick. Some part of my brain must have noticed that he was twisting my wrist one way, then the other, then back, as he unlatched the wristband. Maybe part of my brain even saw him taking the watch. But that information never made it to my mind.

I like my mind. I like free will—or, more likely, the illusion of free will, which might well be the trickiest illusion of all. And magicians use their own (illusion of) free will to subvert it. That’s fascinating—as fascinating as any magic trick. But the magicians who can pull off that trick? Them I’m more scared of than ever.

But now I have decided to face my fear. I’m going to go to the source—to Alex Stone. I’m going to tell him that I’m scared of him and other magicians, and I’m going to ask him why I shouldn’t be—or, I suppose, should be. But that conversation, I’m afraid to say (in more ways than one), will have to wait until tomorrow.

One thought on “Something Up His Sleeve, Part 1”

Comments are closed.