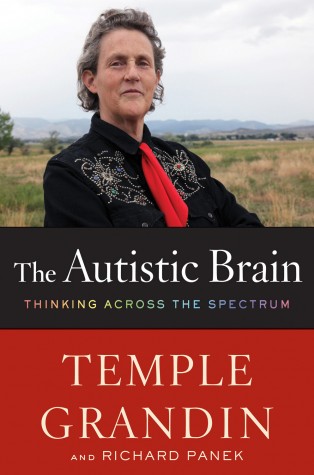

Richard and Temple Grandin have co-authored a book, The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum, which is just out and which you should definitely and immediately buy. Before you do, Jessa and Ann have some questions.

Ann: Richard, this subject is a departure for you. What is the subject, anyway?

Ann: Richard, this subject is a departure for you. What is the subject, anyway?

Richard: The immediate subject is the autistic brain. Hence the title: The Autistic Brain. But we also wanted the book to have a broader audience than the autistic community. As I always tell my writing students, if you want to illustrate the norm, use an anomaly—so in this case, the autistic brain is the anomaly that we use to investigate the whole nature of the brain.

Ann: So Departure #1: the brain?

Richard: Believe it or not, Temple has never really addressed the brain as a subject unto itself. And you’re right, it’s a new area for me (though in my research on Freud for The Invisible Century: Einstein, Freud, and the Search for Hidden Universes I taught myself the state of neuroscience circa 1890). But science itself was new to me when I started writing about it in the mid-1990s. I like challenging myself to learn about new subjects, then to use my learning experience to help the reader understand the science.

Ann: And Departure #2: collaboration? How did you divide up the work?

Ann: And Departure #2: collaboration? How did you divide up the work?

Richard: First, Temple is a great person to collaborate with. She wants you to send her, in her word, “homework,” and when it’s time to talk (which we routinely did at 11 a.m. my time every Sunday), she’s ready to go. Temple arrived at the project with some great new ideas—for instance, that the traditional verbal and visual ways of thinking should be expanded to verbal, picture (or object), and pattern (or spatial). Spatial and object thinking have always been sort of subcategories of visual; in fact, visual thinking is sometimes referred to as object-spatial. But Temple suspected that object thinking and spatial thinking not only use different parts of the brain but that people tend to be strong in one area and weak in the other—so why not consider them to be separate kinds of thinking altogether? Which would explain why, for instance, scientists are so often interested in music; both involve spatial thinking much more than object thinking. Temple tracked down empirical support for this hypothesis in a series of groundbreaking studies by the neuroscientist Maria Kozhevnikov, whom we wound up interviewing at length. The book includes some of the mental exercises that Kozhevnikov and her team devised in conducting their research.

Ann: Ok, and so what was your job?

Richard: I especially like the historical and philosophical aspects of science, so I dug into the history of autism—which, by the way, books on autism often overlook, as if everybody knows the history of autism. But I’ve found that even people in the field don’t know it. (That’s an example of what I described earlier—using my own learning process to figure out how to communicate with the reader.) The history-of-autism chapter (the first half is here) in turn led me to the idea that we can think of the history of autism as having three distinct periods: first, the psychoanalytic (blaming the “refrigerator mother”), which begins with the initial diagnosis in the 1940s and ends in 1980, with the formal inclusion of autism as a diagnosis in the DSM-III (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders); second, the behavioral, in which psychiatry tries to get the definition right by observing the outward manifestations of symptoms and then figuring out what symptoms people with autism have in common, and which ends now, with the publication of the DSM-5 this month; and the biological, which is what state-of-the-art neuroimaging allows. The upshot of Temple’s ideas combined with mine is that for the first time science will be able to address autism on a symptom-by-symptom, individual-by-individual basis.

Jessa: So much seems to have been happening in autism research since you started working on this book. How did you accommodate breaking news as you worked? I’m thinking also of Aspergers being dropped from the DSM.

Richard: We monitored the pending update of the DSM-5 closely, at least until the American Psychiatric Association took the criteria off of the DSM-5 website. We were making changes to the hard science part of the book as late as February, which, if you know publishing, is kind of insane. But worth it! Still, I think that the historical approach I mentioned allows the latest advances to be read as part of an argument for changing the way we think about autism—a perspective that Temple and I hope will make the book long outlive this or that particular breakthrough. In fact, the second half of the book is called, “Rethinking the Autistic Brain.”

Ann: Back to your “the autistic brain as an anomaly:” so really there is such a thing as the autistic brain? Or maybe an overlapping subset among autistic brains? They’ve put a lot of autistic people in MRI machines and found that autistic brains have something identifiable in common? I ask because I read in Science about DSM-5 arguing over whether these psychiatric/psychological/whatever conditions exist as discrete entities, and because I’m so fond of the phrase, “autism spectrum.”

Richard: Well, it is a spectrum. A really, really broad spectrum. One of the arguments we make is that neuroimaging will allow researchers to think outside the “autism” box. Temple and I came across a bunch of studies that group autistic subjects together and look at whether they have a certain trait in common—let’s say, extreme sound sensitivity. Then the studies conclude that people with autism are or are not prone to extreme sound sensitivity. We argue that a more productive approach is to group subjects with extreme sound sensitivity, both autistic and neurotypical, into one study and look at what their brains have in common. As Temple says, “Throw ‘em both in a scanner and let’s see what lights up!”

Jessa: Neuroimaging seems to be reaching a stage where it’s finally making itself genuinely useful, but there’s a danger in overreaching. Ed Yong calls it “neurobollocks.” The “throw ‘em in a scanner” approach leads to statements like “Some autistic people are noise-sensitive because: brain scan.”

Richard: We tried to be very careful about not overreaching, so “Throw ‘em in a scanner” is—

Ann: Ha, Richard. You said “neurotypical.” Are you as a nonscientist allowed to use those science words?

Richard: Only with adult supervision. And I’m not sure this interview counts (I’m looking at you, Ann).

Jessa: You can’t say that word without a nerdy speed-robot voice, I think.

Ann: I interrupted. Jessa, you were saying?

Richard: Actually, Ann, you interrupted me. Nonetheless: Jessa?

Jessa: I guess I was just looking for assurances that this is not a book full of wild assertions. But of course Richard wouldn’t write one of those, so I’m not worried.

Ann: Richard, is the book full of wild assertions? Besides, I don’t think I see the point of finding sound-sensitive people and seeing what their brains, both autistic and neurotypical, have in common. Unless you’re more interested in sound-sensitive brains than in autistic ones.

Richard: What you’re interested in are symptoms. “Throw ‘em in a scanner” is somewhat hyperbolic, but I think it gets the point across: Target the symptom, not the diagnosis. If you’re dealing with something that exists on a broad spectrum, like autism, you shouldn’t have a one-size-fits-all approach—but that kind of thinking has indeed been prevalent. Temple talks about “label-locked” thinking, and that’s what we’re trying to overturn. Being able to proceed symptom by symptom might allow for a more targeted approach to therapy, treatment, intervention, prognosis, and so on. You can already see the beginnings of a shift in this direction. Last September two Yale researchers, Matthew W. State and Nenad Šestan, wrote in Science that they anticipate autism treatment trials will be organized around “shared mechanisms” rather than “psychiatric diagnostic categories.” If a particular autistic person has a sound sensitivity, then let’s try to alleviate the discomfort so that the person might be able to cope better.

Ann: I am now, like Jessa, not worried. What I really want to know is, given that writers want to be rich or famous (choose one), which do you want to be? Or is that question indiscreet? Probably is, right?

Richard: Well, if I absolutely had to make a binary choice, I guess I’d go with, “Famous for the right reasons.”

Ann: Oh Richard. Go ahead. Say “rich.”

Richard: Rich. And famous for the right reasons.

_____________

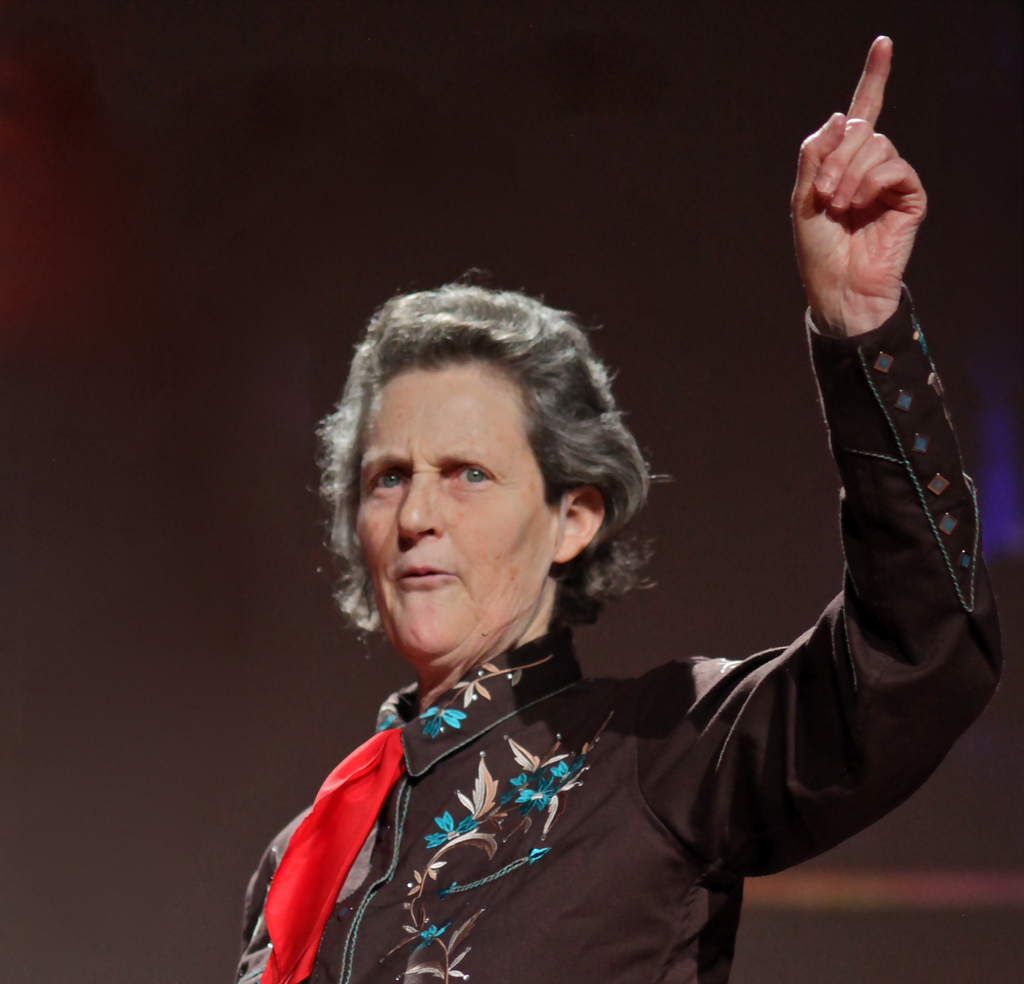

Photo: jurvetson

2 thoughts on “Temple Grandin & a Neurotypical Write a Book”

Comments are closed.