I know Erika already covered the Mike Daisey/TAL/Apple story and so did a lot of other people as smart as she is. But I’m a slow thinker, so I’m coming in to this a little late and out of left field. The left field in this case is epistemology, which is “the study of knowledge and justified belief.” Justified belief — knowing that what you know is reliable and worthy of trust — is why I like science.

I know Erika already covered the Mike Daisey/TAL/Apple story and so did a lot of other people as smart as she is. But I’m a slow thinker, so I’m coming in to this a little late and out of left field. The left field in this case is epistemology, which is “the study of knowledge and justified belief.” Justified belief — knowing that what you know is reliable and worthy of trust — is why I like science.

Science – or physical science anyway – accomplishes all this epistemological goodness by having theorists and observers/ experimentalists stage a running death duel. Theorists take the facts that observers observe or experimentalists find, and arrange them into a theory, a model, a picture, a story – their terms vary. Observers and/or experimentalists narrow their eyes, spit on their hands, and design observations and experiments that blow the theorists’ theories to smithereens. Theorists counter by refining their theories to accommodate the newly-found facts, and the duel continues on and on, years, decades even, centuries sometimes, until theory and fact converge and everybody agrees: for right now, anyway, this is as close to the truth as we can get. Without theory, facts are incoherent; without fact, theory is airy nonsense. Without both, nothing close to the truth.

I’m tempted to say the same duality — coherence vs. complicated reality, story vs. facts — operates in fiction vs nonfiction, but it doesn’t, not really.  Fiction (which I read almost exclusively) is art, a collection of made-up facts and impressions in a made-up world that uncannily evokes in a reader the same world. Fiction can feel true and entirely believable – no marriage is ideal, let’s quietly adjust to each other – until you read the next novel which makes it clear, you just throw the bastard out. Readers expect fiction’s truths to be like this, idiosyncratic and partial and temporary; and they don’t mind because they’re in it for the evocation, the experience of someone else’s world. They’re not in it for truth about the world we must share.

Fiction (which I read almost exclusively) is art, a collection of made-up facts and impressions in a made-up world that uncannily evokes in a reader the same world. Fiction can feel true and entirely believable – no marriage is ideal, let’s quietly adjust to each other – until you read the next novel which makes it clear, you just throw the bastard out. Readers expect fiction’s truths to be like this, idiosyncratic and partial and temporary; and they don’t mind because they’re in it for the evocation, the experience of someone else’s world. They’re not in it for truth about the world we must share.

It’s nonfiction that fights the duel, that arranges facts into a story, that finds the story in facts. Readers are in it less for evocation of someone else’s world than for understanding our own. Without facts, nonfiction is unreliable and readers’ understanding of the world is correspondingly untrustworthy. Untrustworthy narrators in fiction are charming; in nonfiction, they’re worse than useless, at best a waste of time.

Let me tell you a story. Years ago, I was running a workshop class for young science writers. One of them, a medical writer, sent around a story to be discussed by her classmates, who liked the story. The first paragraph was an anecdote about some parents whose son had some disease, talking out their grief and fear. The class liked the anecdote, they cared about the parents. But the anecdote was made up, said the young writer. She hadn’t had a chance to talk to the parents yet; she had an appointment though. The class was really pissed. They were so pissed I was surprised. She had a good reason for making up the anecdote, I thought, she wasn’t really lying to them. Then I thought, her reasons and intentions are irrelevant. What’s relevant is that they believed her and what she said wasn’t the truth. They believed a thing that was untrue and that she knew to be untrue. She looked them in the eyes and lied. She betrayed them; they wanted her taken out back and shot.

And that’s why — epistemologically, intellectually, personally — the line between fiction and nonfiction is of necessity so hard and so bright.

__________

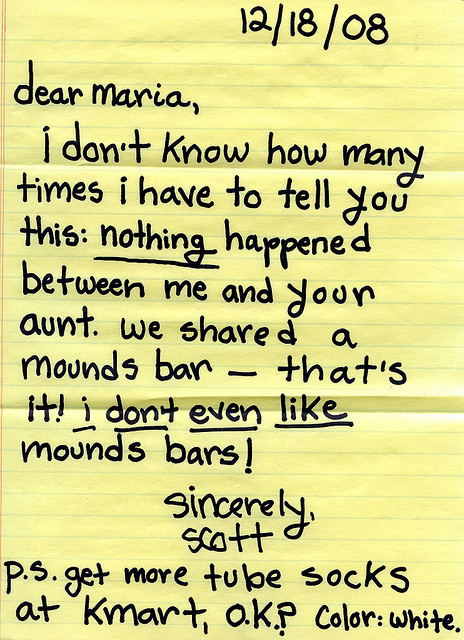

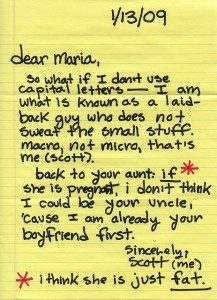

Photo credit: John McNab, from the Scott and Maria series of letters he claims to have found in the alley. Unreliable narrator if ever there was one.

Three cheers for slow thinking, Ann!