One bright day last December, certain science bloggers who had happily discovered a shared taste for classic mystery writers, all wrote synchronous posts about the science in mystery books. These books, we thought, have a surprising amount of good science in them. So we’re doing it again (for titles, see bottom of post). This post is about Dorothy Sayers’ Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club.

On Armistice Day, some years after the first World War is over, an old general is found dead, sitting in his usual chair by the fire at his club, the Bellona Club. Oddly, he’s not wearing in his lapel the usual remembrance poppy. He’s very old though, he must have died naturally; his body is removed from the club and life goes on. A number of plot developments later, however, he’s found to have been murdered. The last person to see him alive was his grandson, Captain George Fentiman, who was in the war and who has been mentally and emotionally unbalanced by shell shock.

George Fentiman is still too sick to hold a job, badly needs money, is his grandfather’s beneficiary, and so is the logical suspect in the murder. He’s an unpleasant character: he’s bitter about his service to the country, he berates his wife who has to support them both; he’s nervous and jumpy and picks fights for nothing. These symptoms of shell shock also make him a suspect. Once he understands this, he takes one of his “queer fits,” disappears for days, and when he returns, confesses to the murder. He didn’t do it though, and our detective Lord Peter Wimsey knows he didn’t and uses his confession to reveal the real murderer.

George Fentiman is still too sick to hold a job, badly needs money, is his grandfather’s beneficiary, and so is the logical suspect in the murder. He’s an unpleasant character: he’s bitter about his service to the country, he berates his wife who has to support them both; he’s nervous and jumpy and picks fights for nothing. These symptoms of shell shock also make him a suspect. Once he understands this, he takes one of his “queer fits,” disappears for days, and when he returns, confesses to the murder. He didn’t do it though, and our detective Lord Peter Wimsey knows he didn’t and uses his confession to reveal the real murderer.

Wimsey in fact was also in the war, also has shell shock, and at times of stress, believes he’s back in the trenches. So Wimsey knows enough to understand what Fentiman is going through and in particular, what he means when he says that his grandfather, the general, may have been in the Crimea, but had no idea of what real war was like.

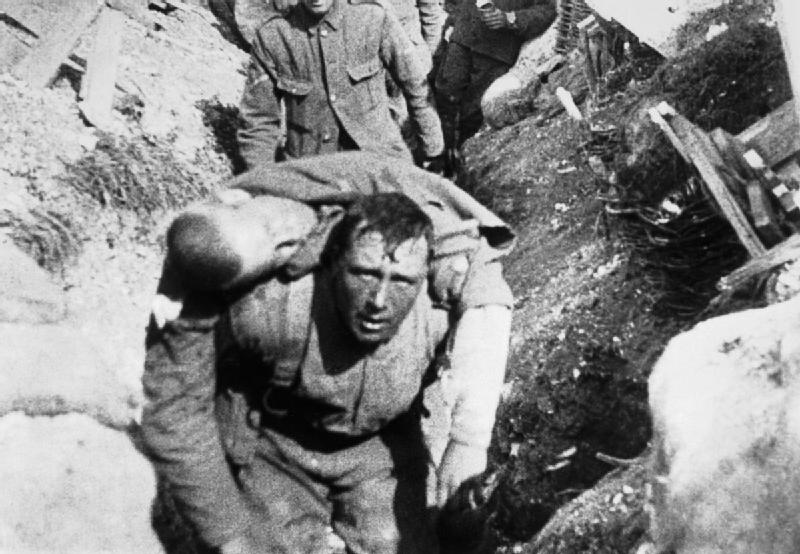

World War I was the first modern war, that is, a war with unimaginably large numbers of soldiers, terrible new technologies, and the wholesale blind slaughter of trench warfare. The opposing armies occupied fortified trenches a hundred or so yards apart. Their artillery — with vastly improved range, accuracy, and firepower — fired shells full of shot that burst in the air above the opposing trenches. Then wait for a lull, go over the top, cross the no-man’s land, and if your artillery hadn’t killed the guys in the other trenches, you shot them; alternatively, you waited for the other guys to come shoot you. The armies also used poison gas, which hugged the ground and rolled over the soldiers in the trenches, blinding, burning, blistering, and suffocating them. Wimsey was on the Western Front, at Caudry, one of the battles of Le Cateau, and was buried alive when the fortification of his trench collapsed on him; when his troops found him, they thought he was dead. George Fentiman was gassed. Neither gas nor trench warfare were effective tactics for winning battles; they were better at killing and maiming. The war was, even compared to all previous wars, unspeakable.

World War I was the first modern war, that is, a war with unimaginably large numbers of soldiers, terrible new technologies, and the wholesale blind slaughter of trench warfare. The opposing armies occupied fortified trenches a hundred or so yards apart. Their artillery — with vastly improved range, accuracy, and firepower — fired shells full of shot that burst in the air above the opposing trenches. Then wait for a lull, go over the top, cross the no-man’s land, and if your artillery hadn’t killed the guys in the other trenches, you shot them; alternatively, you waited for the other guys to come shoot you. The armies also used poison gas, which hugged the ground and rolled over the soldiers in the trenches, blinding, burning, blistering, and suffocating them. Wimsey was on the Western Front, at Caudry, one of the battles of Le Cateau, and was buried alive when the fortification of his trench collapsed on him; when his troops found him, they thought he was dead. George Fentiman was gassed. Neither gas nor trench warfare were effective tactics for winning battles; they were better at killing and maiming. The war was, even compared to all previous wars, unspeakable.

And maybe because of its large numbers or maybe its unspeakability, it was also the first war to pay attention to what was called shell shock. At first, doctors thought symptoms like Fentiman’s and Wimsey’s were neurological, the result of the physical shockwave from bursting shells. Then when doctors discovered that not everyone with shell shock had been subject to shockwaves, they thought the symptoms were psychological and cropped up only in sensitive natures: George inherited a weakly strain from his grandmother, says his lawyer. George turned out to be ok, once the murderer was found and his inheritance was secure; the book ends with him “getting on splendidly.” Wimsey never got past his shell shock but it affected him only rarely. Which was just as well because in general, the medical/psychiatric community downplayed shell shock and couldn’t do much about it anyway.

And maybe because of its large numbers or maybe its unspeakability, it was also the first war to pay attention to what was called shell shock. At first, doctors thought symptoms like Fentiman’s and Wimsey’s were neurological, the result of the physical shockwave from bursting shells. Then when doctors discovered that not everyone with shell shock had been subject to shockwaves, they thought the symptoms were psychological and cropped up only in sensitive natures: George inherited a weakly strain from his grandmother, says his lawyer. George turned out to be ok, once the murderer was found and his inheritance was secure; the book ends with him “getting on splendidly.” Wimsey never got past his shell shock but it affected him only rarely. Which was just as well because in general, the medical/psychiatric community downplayed shell shock and couldn’t do much about it anyway.

Since then, wars – World War II, the Korean War, the war in Vietnam — continued to improve their technologies and shell shock turned into post-traumatic stress syndrome. The medical/psychiatric community continued to downplay PTSD and couldn’t do much about it anyway. But with the wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan, that’s been changing. Diagnosis has, since 1980, been standardized: a traumatic experience — intense fear, horror, or helplessness from a threat of death or serious injury to yourself or people next to you – that you re-experience either in flashbacks or dreams, to which you respond with avoidance, numbness, or detachment, and irritability, hypervigilance, or over-reaction.

With a standardized diagnosis, scientific studies can be done, including neurological studies that find that nearby explosions can physically change the brain after all. Treatment of PTSD is still uncertain: psychotherapy can include controlled and safe exposure to the original trauma; no drugs seem to work.

With a standardized diagnosis, scientific studies can be done, including neurological studies that find that nearby explosions can physically change the brain after all. Treatment of PTSD is still uncertain: psychotherapy can include controlled and safe exposure to the original trauma; no drugs seem to work.

Meanwhile, of course, science has continued to improve war’s technologies. I once did a group interview of physicists involved in defense work who repeated an old saying. World War I, with its poison gas, they said, was the chemists’ war. World War II, with its rocket attacks and nuclear bombs, was the physicists’ war: “Ours was much more honorable,” snorted one physicist, “because we didn’t gas people. We killed them another way.” World War III will be the biologists’ war. “Well,” said another physicist, “Einstein said he didn’t know how World War III was going to be fought, but he knew World War IV would be with bows and arrows and spears.” A third physicist chortled: “The metallurgists’ war,” he said. They all laughed and I don’t think one of them thought it was funny.

What do you bet that the psychiatrists who couldn’t keep up with the chemists and physicists, won’t even be able to keep up with the metallurgists? Too bad, isn’t it, that technologies are so much simpler than minds.

_______________

Credits: German soldier at the Battle of the Somme, 1916 – Bundesarchiv

British trenches at the Battle of the Somme, 1916 – Imperial War Museum

British soldiers at the Battle of the Somme, 1916 (the man being carried died a half hour later) – Imperial War Museum

Russian soldier at the Afghan War, 1986 – RIA Novosti archive

_______________

The current Science of Mysteries series: Deborah Blum on Agatha Christie’s The Mysterious Affair at Styles; and Jennifer Ouellette on Sayers’ Gaudy Night.

The first Science of Mysteries series: Jennifer Ouellette on Sayers’ The Nine Tailors and on Josephine Tey’s The Singing Sands and on Jane Langton’s Dark Nantucket Noon; and Deborah Blum on Sayers’ Strong Poison

Have you read the recent Dream fever, by Preston & Child. There is Audubon and some neuroscience.

Interesting post. You may be interested to know that the historian Clive Emsley has been doing some fascinating research in recent years on First World War veterans and fears of crime in the 1920s. One example can be downloaded here: http://oro.open.ac.uk/10655/

It focuses less on the science of ‘shell shock’ and more on the press and institutional reactions to large numbers of potentially ‘brutalised’ men to civilian life.

For great fun, you can’t beat Alan Bradley’s Flavia DeLuce novels, the precocious sleuth: history of science, Victorian science, toxicology, chemistry…

Manuel, I haven’t read Dream Fever and, given the authors, I certainly should have. In this Science of Mysteries series, though, for some reason we’re concentrating on the classic (i.e., old) mysteries. But thank you, I’ll add Dream Fever to my list.

John, that’s interesting. I know that war had a huge effect on literature and painting too, so surely it would have had a general effect on social institutions.

Elaine, I’m checking it out pronto. Thank you.

Good post, and a strange coincidence: I read this immediately after dinner with one of the people behind this project, so that some of what you write about changes to the brain seems weirdly like dejà vu. He was saying that one of the things that seems to lessen the effects of PTSD is being able to act against the threat, so that it is often the case that refugees, and especially refugee children, suffer worse than combatants. I don’t know whether to be upset or encouraged by this research, since at least some of it appears purposable for allowing soldiers to fight for longer with less consequence, but the refugee string of it can only be viewed positively I think.

Jonathan, I purposely didn’t broaden PTSD to include all the people it does properly include. And that argument about helplessness makes enormous sense. One source — I don’t remember which — said that soldiers are no longer evacuated out when a PTSD-trigger happens, but kept near their companies and treated more or less on site. That makes sense to me too.

I read Sayers’ books with great enjoyment some years ago, and I thought her treatment of Lord Peter’s shell shock was very sympathetic – reflecting the knowledge and attitudes of the times.

The shell shock also deepened the tie between him and his gentleman’s gentleman, Bunter, who followed him as a sargeant into the trenches, and cared for him in both military and civilian life. Neither man is criticised for either caring or being cared for; it’s just part of their life together.

Charles Todd (actually a mother and son team) writes the Ian Rutledge series of historical mysteries, which feature a Scotland Yard detective inspector who is also a WWI vet and PTSD survivor. They’re good books, very much in the Anne Perry vein, and quite effectively portray the ignorance and prejudice (from the public, the medical community and military command) that surrounded shellshocked veterans.