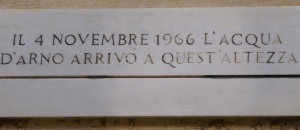

To the left is a courtyard in the Church of the Ognissanti, All Saints, in Florence, Italy. You can’t see it in this picture, but above the little staircase, near the top of the doorway, about where the arch meets the wall, is a small sign. It’s something like the one above: In 4 November, 1966, the waters of the Arno came to this height.

Florence is full of these signs. Most of them are from 1966, which was the most recent and worst of centuries of regular floods. They happen every 15 years or so, 56 of them since the first historic bad one in 1177. The Arno floods because the local weather swings wildly between dry and rainy and when it rains, it doesn’t stop. I was there in 2010, when it rained for 10 days straight, and while the Arno didn’t flood, for days it was ugly: it was a thick brown and fast, full of waves and whorls, making a continuous low roar. When the Arno does flood, it takes out the bridges, people lose their homes and businesses, ancient art and books are destroyed, people die. The flood in 1333 wasn’t the worst, but its timing was bad and for the next 15 years, Florence was visited by one disaster after another. And after disaster came the Renaissance.

In the few years before 1333, Florence was politically, culturally, and financially so rich, it had to pass sumptuary laws against too much elegance. In 1333, though, it rained for days and by November 4, the Arno had washed away three of the four bridges and part of the city wall, and filled the streets; churches were flooded up to their altars, their bells rang in prayer, and around 300 people died; it was God’s judgment on them, people said. In 1342, the government was taken over by a despot and the populace rebelled, successfully, but the succeeding governments were insecure. In 1346, the great Florentine banks, which were the girders under the Florentine and the European economies, had lent a kingdom’s worth of money to Edward III of England for a war, and when Edward lost the war and defaulted on the loan, the banks collapsed and so did the economies. The same year and the following one too, the crops failed and the people who were already out of work began starving. Then in the spring of 1348, the Black Death moved into Florence and killed around 60,000 people. They died terribly and so fast, they couldn’t be mourned. They filled the church graveyards, then the newly-dug trenches around the churches; they were stowed like cargo, people said. 60,000 people was about three-fifths of the population.

I can’t quite take this in. God is angry, the government doesn’t work, the economy is wrecked, people are out of jobs, they can’t find food. And now the plague, and it infects everyone regardless. You have five co-workers, three are dead. You have five friends, three are dead. You have five people in your family, three are dead. How would the people react to that, how could they process that kind of loss?

Catastrophes are often processed through art, of course, and what with Giotto and his school, Florence was a hotbed of art. Art history books say that Florentine painting for the decades after the disasters was stiff, symbolic, and preoccupied with death. And it’s true that in the Uffizi — that one-building class in the history of art — the paintings in the next rooms after the Giotto room are hard to get through. The colors are murky; the saints and martyrs look bodyless, acquiescent, and hopeless; nothing good will come of this world.

The rooms after those, though, beginning 50 years after the plague, are one after another, a slow revelation. The art history books say that around 1400, Florence got interested in humanism, rationality, and classicism; and its economy improved enough that merchant princes and international bankers began commissioning art.

But that can’t be the whole story because the art was astounding: the fourth room after Giotto, just fifty years after hopelessness, where did those paintings come from? You go to the next room and the next, and somehow or another, the next paintings have gone even farther; they’re stunning, literally; you look at them and can hardly breathe.

Would humanism and rationality have this kind of power? To make beauty that takes your breath away? Wouldn’t that kind of power come instead from the plague? How long does a culture take to process great loss? I don’t think anyone’s studied this. I know that the children and grandchildren of the Holocaust are still dealing with human evil. My mother was a child on a tenant farm during the Great Depression, and I’m still rinsing out plastic bags and re-using them.

I’m going to make an argument here, but I’m not going to make it with words, I’m going to make it chronologically and visually. I’m using only annunciations, partly because the similar subject makes for easier comparison, partly because I’ve always loved annunciations. The argument is as follows: Florence took fear, grim death, and grief, and gradually over years created beauty.

I’ll say it again: after fear, disaster, disease, death, and grief, decades or generations later, people took unrelenting loss and made great beauty.

_______________

Not all these pictures are in the Uffizi. But they are all Florentine or at least Tuscan — that is, the artists were all looking at each other and at the artists earlier.

Much of this information came from four books: Florence: A Biography of a City, by Christopher Hibbert; Florence: The Golden Age, by Gene Brucker; The Art of Florence, by Glenn M. Andres, John Hunisak, & Richard Turner; and The City of Florence, by R.W.B. Lewis.

Photo credits: courtyard – me; sign – Old Fogey 1942; Annunciations – Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons, while wonderful in every way, doesn’t concern itself overmuch with accuracy in color.

How long does it take? You do ask good questions! At a guess I’d say ‘two generations’ – but the persistence of memory gets stretched out more and more as we find new ways of preserving it. Too many variables, at least for this time of the evening!

This is great, possibly the best way to explain the emotional sea change in society at the time(s). I was looking at Gabriel’s wings and the change in their texture, color, and detail.

Giotto’s are the most like what I think a “traditional” angel wing looks like – if I were to open a Golden Book of the Annunciation, that is what I’d see. Then we go from Martini’s hard edged moth-esque pair, to tie-dye (you know how the 70s were), to Fra Angelico’s beautifully ordered Amish quilt – comforting, reflecting the specificity of the perspective and architecture – to Lippi’s peacock (silly, if you ask me, but then again, so’s the setting), to Botticelli, who has presented the most alive pair in the bunch (Fra Angelico is a close second).

These heavenly jetpacks are no longer flat and lifeless, sticking out like cardboard twins. We’ve gone from an awkward prop to something that looks like it just might lift Gabriel back to the heavens at any moment. That says progress to me – Gabriel in the school play to Gabriel as divine agent of change.

(I look forward to seeing these with better color as well.)

Thanks Ann.

Spence, you’re always so right about these things. I’m partial to Martini’s and Fra Angelico’s wings, myself. But you’re exactly right about Botticelli’s. In a related matter, I have a private line I draw between the Mannerists and the Renaissance earlier than Michaelangelo: on the later side of the line, angels were a symbol or something and on the earlier, they were damn real. As you said.