Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.

Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.

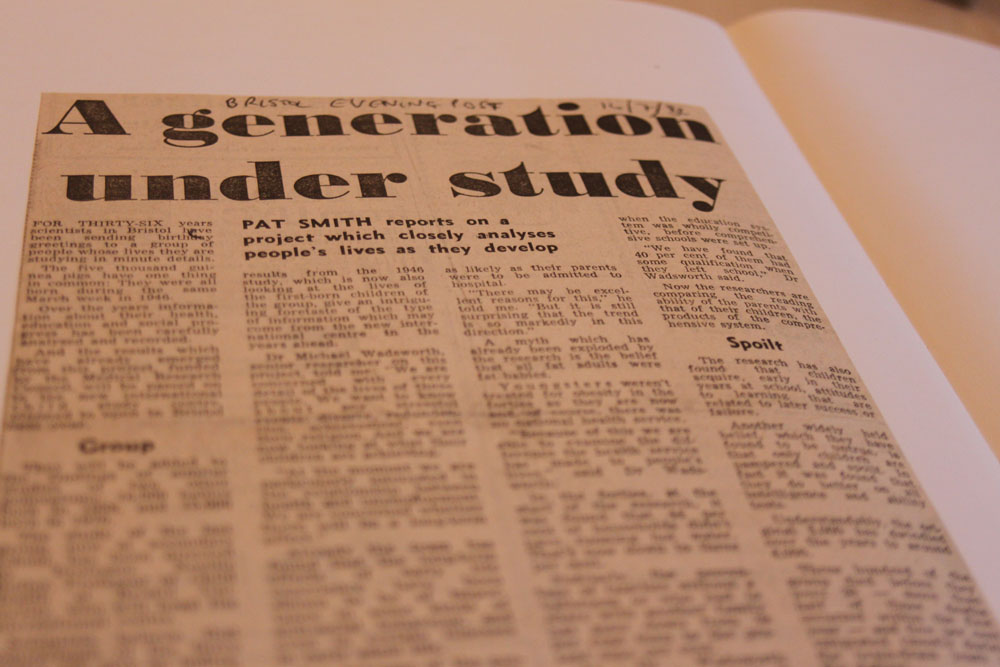

Last year I researched and wrote a feature for Nature about this group and its impact on science. I was able to talk to members of the study about their ordinary — yet extraordinary — lives as they reached 65, Britain’s official retirement age. And in the last couple of months, I’ve been learning more about the series of later British ‘birth cohorts’, born in 1958, 1970, 1991-2 and at the turn of the millennium. Each has its own story.

For each cohort study, researchers have collected records on several thousand babies born at a particular time, and then tracked them over their lives, collecting copious information on their health, development and socio-economic circumstances. The result is a rich encyclopaedia on human life, with some remarkable entries. One of the cohort studies has amassed 12,000 placentas, now in deep freeze. Another has stored 13,000 essays, written by 11 year-olds about their dreams for the future.

The story of each cohort is also the story of a generation. Members of the 1946 cohort were the first baby boomers, born a few months after the end of the war. Data from this group have helped establish links between infant growth and adult characteristics that emerge decades later, ranging from cardiovascular disease to cancer to mental health conditions.

The 1958 cohort grew up in the 60s and 70s, just as parental divorce was on the rise, and studies on the group have explored the long-term legacy of a family split on adult psychological health. The 1970 cohort — Generation X — was the first to experience convenience foods and its data reveals the obesity epidemic hitting hard.

Studies from the early-1990s cohort — soon turning 21 — showed that putting babies to sleep on their backs reduced the risk of cot death and helped re-write advice to parents. (Besides the placentas, the researchers working with this cohort have also banked milk teeth, toenails and urine for biomedical studies.) The 14,000 or so children in the Millennium cohort are already fatter, on average, than any of the older groups, and researchers are starting to explore the impacts of a childhood that is wired with more computers, phones and digital gadgetry than any before.

Yet one result from all the cohorts seems the same. Children who are born into better-off families are more likely, on average, to do well during their lives on almost every measure you can think of. In the 1946 cohort, children born into better socio-economic circumstances were more likely to succeed in education, find good jobs, stay mentally and physically fit — and simply stay alive. The poor were worse off on most counts.

The difference between trajectories of rich and poor is just as stark in the younger cohorts, and the Millennium cohort has revealed how early the gap emerges. Children born into the poorest circumstances were scoring lower on tests of cognitive ability by the age of 3; the gap had widened by age 5.

That early life matters is not a surprising message by now — but seeing it hold true in the various British birth cohorts has still been striking to me. Across the five generations studied, those born into richer families are more likely to have a ‘better’ life on many measures. Does this mean that several decades of initiatives to even out the odds — which in the UK include universal health care, free schooling, plus various early education and parenting support programs — have made little difference? “There’s not been an evening out of life’s chances,” says Lucinda Platt, who heads the Millennium cohort study. “In many ways it’s got worse, depressingly,” says Lynn Molloy, executive director of the 1990s study, called the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, in Bristol.

The message is not entirely deterministic, of course: some bright children born into poorer families go on to great health and success. There are also established ways to buck the odds: exercise being a pretty well established means for climbing to a better health trajectory, and education and supportive parents the route to a better intellectual one. But in general, the pattern holds.

So what exactly is it about socio-economic status that casts such a long shadow? The Millennium cohort study has begun to find some answers. Better-off parents tend to breastfeed, establish routines for their children, such as regular bedtimes and mealtimes, and read daily to them. This appears to account for a portion of the cognitive gap between rich and poor children — parental education explains a bit more. But plenty of the gap is unexplained and whatever does account for it is unlikely to lead to simple solutions. The cohort studies, “allow us to understand who will succeed or fail but don’t necessarily tell you how to change it,” says Alice Sullivan, who runs the 1970 birth cohort.

In the next year or so, Britain is going to launch its next birth cohort: recruiting 90,000 pregnant mothers and tracking their children from birth, it will be the biggest yet. These kids will arrive just as inequalities in Britain, as in many other countries, are widening, thanks to deepening poverty and austerity measures that are eroding support structures, including those for early education and family support. It’s just as cold and dank as post-war Britain, but without the optimism.

You have to wonder how the socio-economic climate of 2012 is going to shape the babies being born into it. Based on five generations of cohort studies that have gone before, it’s likely to influence their well-being for a long, long time.

_____________

Helen Pearson is chief features editor for Nature magazine in London. She writes when she has time, and has picked up awards for doing so. She is slowly rediscovering Britain, having returned to London after several years in New York.

Twitter: @hcpearson

Email: h.pearson@nature.com

Photo credit: Helen Pearson

Just before I saw the title of your post I had read this: http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2012/01/05/what_x_can_teach_us_about_y_has_become_a_publishing_cliche.html

Helen —

That’s a nice summary of a lot of good work. Kudos to the Brits for undertaking that longterm effort. I find myself trying to sort out two different kinds of explanation for the findings. One is that being in the upper classes provides certain advantages that accrue from educated parents with time and money. In this connection, it would be interesting to know what the studies found in relation to mothers who stayed home versus those who worked.

Another way of looking at the results is that the kind of people who make their way into the middle and upper-middle classes are somehow different from the people who don’t. In the second explanation the benefits of an advantaged childhood could be due to more ephemeral differences. For instance, not something as straightforward as reading or enrichment classes, but attitudes conveyed in nonverbal ways, attitudes about the child’s value and what he/she can rightfully expect in life.

The difference between the two types of explanation is subtle, but, I think, real, and has implications for how much of the benefit of being an advantaged child can be substituted by public programs.

I can’t help but wonder if part of the gap is due to epigenetics. The families with lower socioeconomic status may be exposed to more environmental hazards in their neighborhoods (which may be located in less desirable areas) and in their work (manufacturing, etc rather than jobs that are mostly mental). They also are more likely to have a poor diet and higher stress which may induce epigenetic changes. I wonder if there will be any cross-class adoptions in this large dataset that could help separate differences due to grandparent/parent environment and child environment and if anyone will be studying epigenetic differences. Lots to think about!