This post originally ran in November of 2011.

The universality of science – an obligation to produce identical results no matter the setting – removes a certain sense of place from science history. What does it matter where mitosis was first understood, if it could just as well be discovered anywhere in the biosphere? Furthermore, it’s hard nowadays even to pin down a location for scientific advances: authors are listed according to institutional affiliations, often spanning the globe to collaborate on a single journal article.

There is a place, I think, for recognition not only of great minds but also of the physical spaces that have witnessed some of their best work. While laboratory spaces look different now than they used to, it’s well worth revisiting the conditions under which pivotal discoveries were made. Our species is adapted for social learning based on modeling, and the more clearly we can visualize our personal heroes at work, the better we can put ourselves into their minds, applying their ways of thinking to our own professional questions.

I invite you to share in the comments section a building that inspires you in your own appreciation of science, and I’d like to share one of mine with you now.

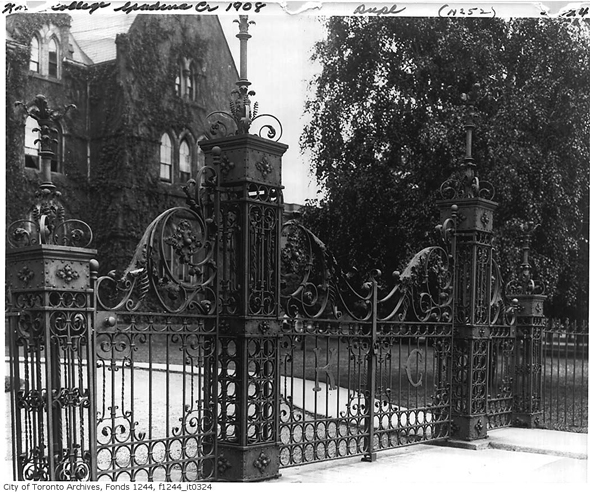

Number One Spadina Crescent is a massive, ivy-covered Gothic Revival building erected in 1875 on the edge of Toronto’s university campus. It stands alone in the middle of a busy roundabout, and until 2007 it was impossible to reach it without jaywalking across three lanes of curving traffic and streetcar tracks.

The place has got the kind of ancient creepiness that’s in short supply anywhere in the New World. Replete with secret passageways and dead-end staircases, it’s an urban infiltrator’s fantasy. The 2001 unsolved murder of a professor, paired with the recent death of a ghost hunter after a fall from its roof, only adds currency to the preexisting haunted feeling. Plus, the excellent eye bank in its south-west wing stores many dead people’s eyes, awaiting transplant.

No doubt its walls saw innumerable deaths in its time as a WWI military hospital and barracks, where Amelia Earhart worked as a nurse’s aide until she herself contracted influenza. Charles Best, the co-discoverer of insulin, oversaw insulin production here in the ‘forties when the building was owned by Connaught Labs, and the facility made vital contributions to Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine.

I’ve often wondered whether mixed-use spaces have as revitalizing an effect in academia as they do in urban planning. It was here in this wonderland of inquiry that I first held ancient arrowheads from the Arctic, one of the directions I would follow for the next decade. It was here that I spent a year putting rats through water mazes in a psychology lab. One Spadina Crescent houses visual artists, Hungarian linguists, architecture faculty, and a student newspaper, all engaged in their various pursuits of knowledge.

Feeling entitlement to and ownership over the place in a way only students can about their colleges, I used to ride my bike through the broad, creaking hallways of One Spadina in the dead of night. I felt embraced by the history of the place and in league with all its occupants past and present. The rapid succession of student generations can mean a loss of institutional memory in places like this, but I would argue the value of that knowledge – of what came before, precisely in the place where you stand every day at your lab bench – rates higher as an inspiration than any prestigious lineage the college itself might have to offer.

Scientists, the people most attracted by the universe’s mysteries, often work in environments otherwise devoid of any mystery at all. Their most tangible sense of the past might be the yellowed covers of their office’s fluorescent lighting, stained from the decades of indoor smoking. One Spadina, in contrast, evokes a sense of multi-dimensional wonder – at the dark secrets of its blocked-off spaces, at the varied history of its uses, and at whatever topic is under study in its high-ceilinged halls.

I agree with this idea that the history of science belongs both nowhere and everywhere, but I think the extent to which that’s true varies with the field. As a chemistry student, I never thought “Wow, I sure wish I could see the place where the first Hoffman degradation happened.” I guess I assumed it took place in a beaker, in a lab, and that they looked very much like my beaker and lab.

But I think fields like geology, anthropology, and ecology could possibly have more “tourist destinations.” And experimental physics. I wonder if the super colliders might become museums one day.

My favorite science-related place is Yellowstone National Park. I like seeing where the heat- and sulphur-loving bacteria live, even though I can’t actually see them.

That is one awesome building!

My favorite scientific locale is Hven, the island that Tycho Brahe inhabited for a while. I’ve never been there (visiting next summer, possibly, though!), but from all I’ve read about Tycho Brahe and that little island where he had his underground lab, and science palace, it seems like a fascinating place. I always think about how it might have been a better time to be a scientist way back then. Tycho Brahe’s life for me represents the romantic adventurism of science as it was before the industrial revolution.

That, and I think it’s so incredible that astronomers were able to make such amazing discoveries given such little advanced technology.

Another such place, even more ancient, is Ancient Egypt, where it seems astronomers had an almost inexplicable knowledge of the sky’s cycles over thousands of years.

I love the Musée des Arts et Metiers in Paris, which exists in the deserted priory of St. Martin des Champs. Collections include all kinds of scientific instruments, and the Foucault’s pendulum featured in the novel of the same name by Umberto Eco.

The Museo di Storia di Scienza in Florence. It’s not a workshop or a lab, but it has astrolabes and quadrants and armillary spheres and I spend forever trying (and failing) to figure out how to use them. The best is Galileo’s little bell-ringing different-distances-in-equal-times instrument and I still don’t believe in gravity.

Ann:

As I discovered this fall, Museo di Storia di Scienza also has one or two of Galileo’s naturally mummified fingers. It exhibits them in the scientific version of a reliquary. Some visitors clearly see him as a scientific martyr.

Interesting that you chose the title “places of worship” for your post. Number one Spadina Crescent began it’s life as the home of Knox College, training “Divines” for the Presbyterian Church in Canada. My nomination for a Scientific worship Sanctuary was the old hall of dinosaurs in the Royal Ontario Museum, now buried under fiberglass reconstructions and blinking lights that aren’t half as evocative as the echoing open space with its bare specimens you could walk around.

Great idea to recognize the locations of great scientific discoveries. I have visited numerous locations in Europe such as Greenwich, where the John Harrison clocks are located. However, my favorite location of science history is the night sky. It is the same sky from where ever we observe. I first saw the Andromeda Galaxy (M 31) from the farm yard of my youth in Kansas, the Southern Cross (Crux) while flying over the Mekong Delta at night in Vietnam and a super nova in Ursa Major (the big dipper) from our astronomy club observatory in New Mexico. In all cases it was the same sky, visible to all and free of any restrictions from bureaucratic institutions dedicated to self preservation rather then the accumulation of knowledge. Unfortunately, we have chosen to pollute the night sky with unnecessary and wasted light. Never the less, the sky is ours to enjoy and to marvel at the past discoveries of many intelligent and dedicated people.

Shelter Island on the eastern end of New York’s Long Island where the conferences which led to Quantum Field Theory comes to mind for me. We imagine those conferences every time we cross the island.

A building that inspires me in appreciation of science?

Your example is pretty hard to beat, especially with such an evocative description and a beautiful photograph. So I won’t compete. Instead, as a counterpoint, here’s a new building that has just won 2011 World Learning Building of the Year according to the World Architecture Forum. The Sainsbury Laboratory in Cambridge, UK. You need to see the photos so here is a link.

http://www.stantonwilliams.com/projects/sainsbury-laboratory/

When talking to the scientists in planning a new building like this, the one thing I am struck by is their emphasis on the in between spaces. The corridors, the canteen, the stairwell. They all say that the multidisciplinary interaction outside the laboratories is what really makes a difference. Your reference to urban planning and mixed use is an excellent metaphor in this respect and I think it is totally applicable to buildings.

That place is unbelievable, David. I’m going to go check it out in person the first chance I get. Thanks for posting the link.

The Oxford Museum of the History of Science, like the Museo di Storia di Scienza by the sound of it, definitely has the relic feel to it. It is full of enough brass-bound instruments to make any steampunk feel a bit light-headed, many many astrolabes and, on one wall in one of the galleries, it has a blackboard on which Albert Einstein wrote during a lecture series he gave there; someone had the bright idea of running off with it rather than cleaning it. It’s only got a fairly simple formula on it – but Einstein wrote it. That seems to make people stop and reconceptualise for a bit when they see it.

I love this post. It’s very well written and it made me thought of a place with scientific history as well. But I cannot think of anything and somehow the Leaning Tower of Pisa just kept popping into my mind. I don’t think it has scientific history although it surely made an interesting study. And I also liked dee friesen’s comment. The sky is perfectly accessible to each of us, and holds more complex wonders than any specific place rooted here on earth.

I stumbled across the Museo di Storia di Scienza on a very hot day while on holiday in Florence. Had I know it was there I would have chosen to have gone, but as it was we just went in to escape the heat.. and found such unbelievable wonders in there that we stayed for the whole day. Didn’t know about the one in Oxford, so thanks for that! I’ll have to make a trip once we’re able to walk around freely again.

My personal favorite is the Stroud museum in the park, it houses no end of local history about mills, local archeology, collections of butterflies, and the worlds first lawnmower! Plus threy do load of cool stuff for children throughout school holidays (under normal circumstances anyway). https://museuminthepark.org.uk/

The first place that came to mind for me is the squash court underneath a playing field at the University of Chicago where scientists built Pile-1, the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear reactor, technology that would then be utilized in the making of atomic weapons. I’ve never been to see it, but I love the old grainy footage from a documentary about Edward R. Murrow. What draws me to this place is its unlikely purpose. It wasn’t an august hall, or a crumbling brick laboratory, but instead an unused, underground box where scientists worked to assemble something that totally scared them. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-fermi-nuclear-energy-atomic-enrico-university-chicago-hiroshima-1126-story.html

As a child I was really into astronomy, and always wanted to visit the Palomar observatory, home of what was then the most powerful telescope in the world. And I guess I still do. My first career science was chemistry, but I got into electrochemistry, materials science, and eventually data science. My scientist hero is Michael Faraday, one of the last of the renaissance scientists before science split into specialties. I would love to see his lab at the Royal Institution.