The best thing that ever happened to the Big Bang is its name. For scientists, the acceptance of a scientific concept depends on its explanation of existing data, its prediction of observable phenomena, the observation of those phenomena, and the duplication of those results. But for non-scientists—well, for scientists, too—the popularity of a concept can come down to a show biz maxim: You gotta get a gimmick.

The best thing that ever happened to the Big Bang is its name. For scientists, the acceptance of a scientific concept depends on its explanation of existing data, its prediction of observable phenomena, the observation of those phenomena, and the duplication of those results. But for non-scientists—well, for scientists, too—the popularity of a concept can come down to a show biz maxim: You gotta get a gimmick.

The need for a name for the origin of the universe didn’t arise until Edwin Hubble’s 1929 discovery of evidence that the universe appeared to be expanding from…something. The “primeval atom,” suggested the Belgian astronomer Georges Lemaître shortly thereafter. The “Primeval Fireball,” suggested the Princeton theorist John Archibald Wheeler, once the leftover radiation from the event was discovered in the mid-1960s. From a commercial standpoint, however, neither term had a chance against the competition.

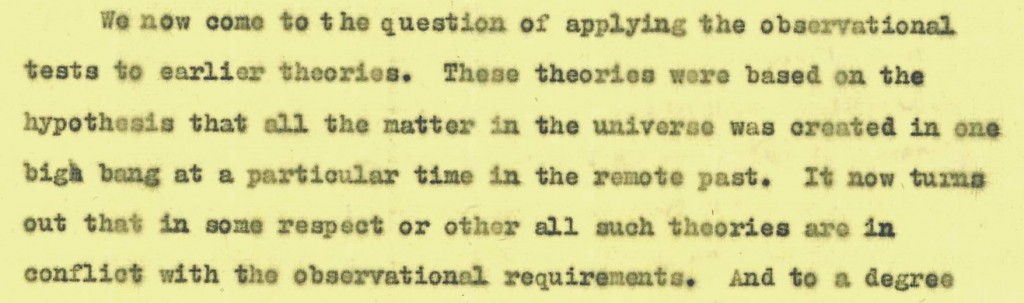

The “Big Bang” was introduced in 1949 by the Cambridge astronomer Fred Hoyle during a series of BBC radio broadcasts popularizing the current state of cosmology. Since then, thanks to a claim by the theorist George Gamow, the legend has grown that Hoyle invoked the term in derision. Derisive Hoyle undoubtably was toward the idea of the universe having an origin; he preferred a universe poised in a “steady state” through the continuous creation of matter. Whatever Hoyle’s intention, however, he couldn’t have done more to secure the idea’s eventual place in the popular imagination than endow it with onomatopoeic alliteration.

“Primeval Fireball,” alas, flopped. But Wheeler could also be commercially canny. The idea of an object with a mass so great that not even light can escape its gravitational grasp had been around since the eighteenth century. In 1916, Einstein’s general theory of relativity provided the math for the existence of such objects, and in 1931 Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar used that math to calculate their mass. The 1965 detection of evidence for a neutron star—extraordinarily dense but not-quite-dense-enough collapsed stars—nudged the theoretical tantalizingly close to the observational. But not until 1967 did the concept begin to enter the public consciousness. Wheeler was giving a talk on the subject when someone in the audience called out the term “black hole,” which Wheeler immediately appropriated for future talks because, he told science writer John Horgan in a 1991 profile in Scientific American, he recognized its “advertising value.”

The Real Theorist of New Jersey was right. From the New York Times review of the new season of “The Real Housewives of New Jersey”: “ ‘The Real Housewives of Orange County’ started it all five years ago, and since then Atlanta, New York and other locales have been sucked into the black hole. Physicists,” the review continued, easing into another metaphor from astronomy, “are now studying the possibility that dark matter involves all the brain cells and hours of potential productivity viewers have wasted watching these shows.”

That term technically dates to 1933, when the Swiss-American astronomer Fritz Zwicky hypothesized the existence of “dunkle (kalte) Materie”—dark (cold) matter—in order to account for the seemingly gravity-defying motions of galaxies in the Coma Cluster. The English translation, however, didn’t come into use until around 1980, when a preponderance of further evidence made the existence of a pervasive unseen substance sufficiently viable that a name for it became necessary.

The success of a shimmeringly evocative term like “dark matter” in capturing the imaginations of scientists and non-scientists alike wasn’t lost on the University of Chicago theorist Michael Turner. In early 1998, two rival teams of observers independently presented evidence that the expansion of the universe wasn’t slowing down, as they had expected, but accelerating. What was this something that, on a cosmic scale, could overwhelm gravity? “Funny energy!” proclaimed Turner at a physics conference that spring, hoping it would catch on with his colleagues. “But,” as he once told me, “the ‘focus groups’ didn’t like funny energy.” A few months later, he slipped into an academic paper the brand name that stuck: dark energy.

“It isn’t the consumers’ job to know what they want,” Steve Jobs once said—a quote that has been much in the news this past week, after he announced his resignation as CEO of Apple. The same principle applies to the consumers of science, whether scientists or the public. You can have a good idea. The idea can turn out to be the right idea. The idea can even be really, really cool. But put the scientific equivalent of an i in front of it, and a star is born.

* * *

Credits: Playbill.com/Joan Marcus; Fred Hoyle Project, St. John’s College, University of Cambridge; Bravo/Virginia Sherwood.

It’s hard to imagine not calling the Big Bang the Big Bang, which probably says a lot about how the word’s entered our consciousness.

Particle physicists also seem to be great at coming up with words…’quark’ is my favourite!

Lovely blog by the way – I’ve only just discovered it.

Thanks, James. You’re certainly right about physicists. And then think of all the acronyms for collaborative projects!

I like Bill Watterson’s “Horrendous Space Kablooey.”