Pambamarca isn’t a household name, not like Machu Picchu. Few backpackers trek its steep slopes each year seeking out the elusive Inca past. There is no sleek Vistadome train, no fleet of gleaming Mercedes-Benz buses whisking crowds to the ruins, no luxury lodge at the top. But Pambamarca bristles with the ruins of Inca ambitions. Five centuries ago, an Inca emperor led a great army to northern Ecuador to conquer the local lords. Pambamarca and the surrounding countryside promptly became the Afghanistan of its day.

Pambamarca isn’t a household name, not like Machu Picchu. Few backpackers trek its steep slopes each year seeking out the elusive Inca past. There is no sleek Vistadome train, no fleet of gleaming Mercedes-Benz buses whisking crowds to the ruins, no luxury lodge at the top. But Pambamarca bristles with the ruins of Inca ambitions. Five centuries ago, an Inca emperor led a great army to northern Ecuador to conquer the local lords. Pambamarca and the surrounding countryside promptly became the Afghanistan of its day.

The region lies roughly 1000 miles northwest of Cuzco, in a land of old snow-topped volcanoes. It’s rough, blustery, high-altitude country, a cold place that has an edge-of-the-known-universe feel to it, or at least that’s the sense I had there. But in the early 16th century, this forbidding land was home to the Caranqui and their allies who wanted little to do with the overbearing empire to the south. To make their position clear, they slaughtered the men that the emperor Huayna Capac sent out to rule them.

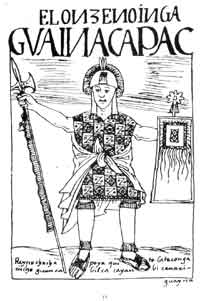

The emperor, whose Quechua name means Powerful Youth, called for conscripts from his provinces, mustering an army of tens of thousands of men. Then he rode north in a magnificent carved war litter, accompanied by his wives and sons, servants and bodyguards. Along the way, throngs of bearers sang his praises and swept the stones clean for his passage, while his soldiers played flutes carved from the long bones of enemy nobles.

But the Caranqui and their allies did not capitulate as this great host approached. They did something unexpected. They united and fought as one, repeatedly ambushing and massacring the invaders, then retreating to ridgetop fortresses on Pambamarca. Faced with such stiff resistance, the Inca emperor followed suit. He ordered his army to build Inca strongholds there, stone-walled fortresses that a team of American and Ecuadorian archaeologists and their students have now spent nearly a decade diligently mapping and recording.

But the Caranqui and their allies did not capitulate as this great host approached. They did something unexpected. They united and fought as one, repeatedly ambushing and massacring the invaders, then retreating to ridgetop fortresses on Pambamarca. Faced with such stiff resistance, the Inca emperor followed suit. He ordered his army to build Inca strongholds there, stone-walled fortresses that a team of American and Ecuadorian archaeologists and their students have now spent nearly a decade diligently mapping and recording.

For years, the Inca army struggled in a costly stalemate in northern Ecuador. Eventually, however, Huayna Capac spied the road to victory. Attacking the fortress of the Caranqui lords with what one later Spanish chronicler called a “great and unstoppable fury,” he lured the enemy into the open and decimated it. Then he hunted down the survivors. Along the marshy shores of a nearby lake, he and his forces slew all who offered resistance, heaving the corpses into the waters of Yahuarcocha—a Quechua word meaning “Lake of Blood.”

Today ice cream stands and paddleboat rentals crowd the shores of Yahuarcocha. Ecuadorian children run gleefully through the reeds. But the Inca emperor and his army left one last bitter legacy. Early last century, drought lowered the waters of Yahuarcocha, revealing a shoreline strewn with human bones. And recently Ecuadorian divers recovered fragments of 500-year-old human crania from the lake bottom. Forensic studies revealed that these individuals died from skull-cracking blows to the head.

We admire the Inca–rightfully–for their organizational genius and their artistry in stone. But we should not forget that the glory of empire always comes at a cost, a very high cost.

Upper photo: Northern Ecuador, courtesy Dr. Carlos Costales Terán. Lower Photo: Illustration of Huayna Capac by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, about 1615.

Incredible story! The Inca have always fascinated me. Just reading this post makes me want to load up Civilization and play as Inca. It’s been a while since I’ve played that game.

Hi Steven: I’ve heard about Civilization but never actually played it and didn’t realize you could take the part of the Inca. That sounds very cool: I’ll have to try it.

The style of writing seeks to impress.. and I’m carried away. But shouldn’t History be written in an objective, scientific manner?

Hi Gerry:

What I’ve done here is synthesize a great deal of research into a short narrative post. I’ve personally visited the fortresses in the Pambamarca region, as well other key Inca archaeological sites in northern Ecuador; interviewed archaeologists working on these sites; read carefully what Spanish chroniclers had to say; and tried to make sense of it all. If you want to read the archaeologists’ own scientific writing, I advise you to delve into the archaeological literature on the Inca kings and the Inca invasion of northern Ecuador.