A few weeks ago, the Human Brain Project announced that it had been selected as a finalist in a competition whose winners will get €1 billion worth of funding from the EU. The Human Brain Project (HBP) plans to use the prize money to build a simulation of the human brain on a supercomputer.

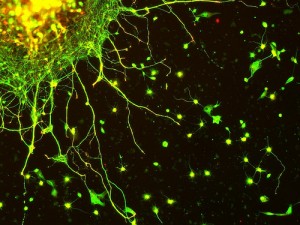

HBP is a consortium of heavy hitters, combining neuroscience expertise with supercomputing know-how. The project’s leader, Henry Markram, has been working towards this goal for years with HBP’s predecessor, the Blue Brain project. Markram is a big deal; in the mid-1990s, he identified a crucial property of the brain’s function called spike timing dependent plasticity, a property of neurons that explains, for example, how they wire together to form memories. In 2005, he partnered with IBM to build a detailed model of the neocortex–the part of the brain that’s involved in perception and conscious thought–on what was at the time the world’s fourth-fastest supercomputer, the Blue Gene L (which explains the Blue Brain moniker).

A full-scale brain simulation would help us obtain insights into neurological disorders and perhaps even untangle the neurobiological underpinnings of intelligence and personality. No Blue Brain story was complete without hints that the Blue Brain simulation might become conscious: When I interviewed Markram in 2008, he told me that he envisioned a Pinocchio-like entity that would autonomously surf the internet to develop and augment its understanding of itself and its universe.

Big plans! But, over the past couple of years, no one seems to done much investigation into Blue Brain’s actual progress, instead repeating that we might be on the brink of building a conscious machine. As far as I can tell, the Blue Brain/Human Brain Project team is still working with a single simulated neocortical column, a 2 millimeter-diameter hunk of brain matter that contains 10,000 of the brain’s roughly 100 billion neurons. I suspect that further research will get underway when the EU funding happens, and now that they’ve gotten a supercomputer upgrade from IBM.

And when that happens, it’s important for us tech journalists to bring our A-game. Because to quote everyone’s favourite AI, “All this has happened before, and all this will happen again.” If the coverage of the Blue Brain project in the past few years is any indication, journalists covering the Human Brain Project will fall down some familiar rabbit holes.

Tech journalism can sometimes fall prey to the effects of one party wanting the attention of readers and the other party wanting the attention of funders. I am not criticizing the Blue Brain project, which has ambitious, noble, and important goals. I’m not criticizing tech journalists, either. I’m not even in a position to solve this problem, but I will analyze the situation, wave my arms at a solution, and perhaps coin a couple of cute terms. Sorry, that’s all you get.

First, a defense of tech journalism. Our problem is that we’re always choosing from among an embarrassment of riches. So many cool projects are underway all around us at all times, which is great! Except for the part where we always have to make sure we don’t miss the next Facebook, the next iPhone, or the next Internet. You’ll have noticed that there aren’t a lot of articles ripping brand new technologies to shreds. That’s because we all have repeating nightmares about becoming this poor guy, who declared boldly in 1995 that the only idea more patently absurd than e-books and digital newspapers would be shopping on the internet. (To add insult to injury, the internet will preserve his prognostications forever.)

Such gruesome cautionary tales make us very careful indeed about pronouncing that a thing will never happen. The result can look a bit like boosterism—by the time it’s become clear that no one is ever going to build a flying car, we’ve already moved on to the flying train, and who has time to catalogue every wrong prediction?

That’s why you’ll find the back issues of your favorite tech magazine stuffed to the gills with prophesying twaddle that doesn’t even hold up for a full year. In 2008, IBM would fill all its future chips with air! The following year, Intel would destroy the graphics microchip market with a monster called Larrabee! That same year, the same journalist predicted that we’re all about to chop off our arms so we can be DARPA cyborgs. Okay, she didn’t actually go that far, but she sure blew a lot of hot air about a “next-generation” prosthetic arm that, two years later, is wastin’ away again in DARPA-ville. (FYI, that litany of fail is all mine. I will never be a futurist.)

Tech journalism has a long track record of not being held accountable for these kinds of pronouncements. As long as you invoke a little “algorithmic magic” or “blazingly fast supercomputers” people will suspend their disbelief. However, readers have memories like elephants. Disappoint them often enough, and soon they’re sour on the whole concept of AI.

This is why, my dear LWON readers, I’m sharing my critical assessment of technology checklist, two things to keep in mind when you’re reading about a new tech breakthrough. I learned them at IEEE Spectrum, from a very cynical editor who prided himself on raining on the parade. He was always right.

1) The Day Old Chinese Food rule

Last night’s Mu Shu pork wasn’t great. But here you are at lunchtime, watching the burbling goop do slow pirouettes in the microwave. You know that MSG-laden mess will taste no better today. The same is true for that technology that sounded kind of promising a couple of years ago but didn’t seem to go anywhere. Re-heating it 5 years later won’t do much good. The breakout surprises—like Twitter; who the hell saw that coming?—tend to come out of left field and don’t require journalistic happy talk to set the world on fire.

To make our case, let’s pick on the flying car again. The first “working model” was introduced over 100 years ago. But it won’t become a commercial success for good reason: what makes something a safe car is the opposite of what makes it a safe plane. This year, it has been reborn as the “air jeep.” Will 2011 finally bring the rapture of the flying cars? Unlikely.

2) The Goldilocks rule

This rule stipulates that your project will bear fruit in 10 years. Not 8 or 13, certainly not 5 and for heavens sake not 20.

Here’s why it has to be 10. When you want money for an open-ended project, you don’t say you’ll expect results in 5 years because then your starry-eyed donors will be breathing down your neck in two. If you say 20 years, they won’t donate because no one feels absolutely certain that they will be alive 20 years from now. Especially not elderly donors. But 10 years? That’s a risk worth taking.

So, for example, let’s look at Blue Brain, which is far from the only project that’s followed the Goldilocks rule.

2005: “Within ten years, he predicts, column models could be duplicated and connected to create simulations of the whole cortex and eventually the whole brain.”

2008: “But if computing speeds continue to develop at their current exponential pace, and energy efficiency improves, Markram believes that he’ll be able to model a complete human brain on a single machine in ten years or less.”

2009: “Researchers hope the breakthrough could lead to a fully virtual human brain within ten years.”

2011: “Scientists will have to assemble countless other partial models, which are to be combined to create a functioning total simulation by 2023.” (that’s 2013 + 10 years for the astute reader, because funding won’t come through until late 2012)

Flying cars and artificial brains aren’t the only technologies that can run afoul of these criteria. Renewable energy stories are also susceptible. Consider the Portuguese water noodle that was going to take wave power mainstream. That is, until the funding ran out and the researchers pissed off and got another life.

Just to be clear, I don’t believe any of these projects are undertaken in bad faith. Most of them are rigorous, and the science is solid: the scientists behind the Human Brain Project, for example, have published enough papers that, if laid end to end, they’d probably reach the moon. It’s also worth noting that not all research bears immediate fruit, and it certainly shouldn’t always be judged on those merits.

You never know, maybe HBP will find the key to ending depression. I’d happily eat my share of crow for that. Until then, however, let’s make sure that tech journalism doesn’t become boosterism.

For these purposes, it wouldn’t be very illuminating to confine the tracked emotions to the basic six that were so helpful for people on the autism spectrum. So, Picard and el Kaliouby started working on new research to identify other, more germane expressions. In March, Picard and her colleague Mohammed Hoque reported that they had tuned a facial expression recognition[sa1] algorithm to pick up the subtle differences between smiles of frustration and delight. Did you know that people often smile[sa2] when they are frustrated? How sure are you that you can spot the difference? [[Will the coming algorithms be capable of better microsecond accuracy than people?]] Picard is pushing her research much further into the subtle, murky areas that trip up neurotypicals. The new research is not yet published, but she hints that the algorithm will help identify other “bespoke” emotional states in the wild, not just in a controlled setting.

[sa1]Acted vs. natural frustration and delight: Many people smile in natural frustration

(Ehsan) Hoque, Mohammed; Picard, Rosalind W.;

MIT Media Lab, Cambridge, MA, USA

This paper appears in: Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition and Workshops (FG 2011), 2011 IEEE International Conference on

Issue Date: 21-25 March 2011

On page(s): 354 – 359

Location: Santa Barbara, CA, USA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4244-9140-7

Digital Object Identifier: 10.1109/FG.2011.5771425

Date of Current Version: 19 May 2011

[sa2]Second, in 90% of the acted cases, participants did not smile when frustrated, whereas in 90% of the natural cases, participants smiled during the frustrating interaction, despite self-reporting significant frustration with the experience.